Week-to-Week: Headless, YouTube, and Webseries in the Algorithmic Age

Insights into making and releasing narrative short form content a decade after its peak

Week-to-Week is Episodic Medium’s free newsletter, which arrives in your inboxes on whichever day is most feasible. For more newsletters, and updates on the shows we’re covering weekly, hit the button below to subscribe.

When I started working as a TA for media studies courses in 2011, the “Intro to TV” course had an entire week’s screening devoted to the “webseries.” As we laid out the disruptions happening to traditional broadcast television, in an era before streaming originals, it was happening on YouTube and other platforms, whether through formal professional affairs like Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, indie success stories like The Guild, or grassroots hits like Issa Rae’s Awkward Black Girl. The following years would see his like the Emmy-winning The Lizzie Bennet Diaries—which I wrote about back in 2013 and 2014, and which star Ashley Clements is currently revisiting on her YouTube channel—and its followups Emma Approved and Welcome to Sanditon, along with an incredibly wide range of projects by marginalized creators who embraced the open distribution of YouTube and Vimeo to reach audiences with their stories.

I highly recommend that anyone interested in this period check out Aymar Jean Christian’s book Open TV: Innovation Beyond Hollywood and the Rise of Web Television, which really captures how much this type of web content was far more influential in changing industry norms than Netflix’s early originals, which were just HBO shows produced for a different distributor. But last fall when I was putting together a lecture on how digital distribution had fundamentally transformed how musicians, game designers, and even to an extent filmmakers reach their audiences, I realized that by comparison the television industry has been far more successful at absorbing disruption into its existing business models. Which is to say that while webseries may have changed how the television industry approached development, the scripted webseries as a format was largely rejected by Hollywood, in ways that have left it little oxygen to work with among audiences—and, perhaps more importantly, algorithms—in an era of Peak TV, as evidenced by Quibi’s quick death.

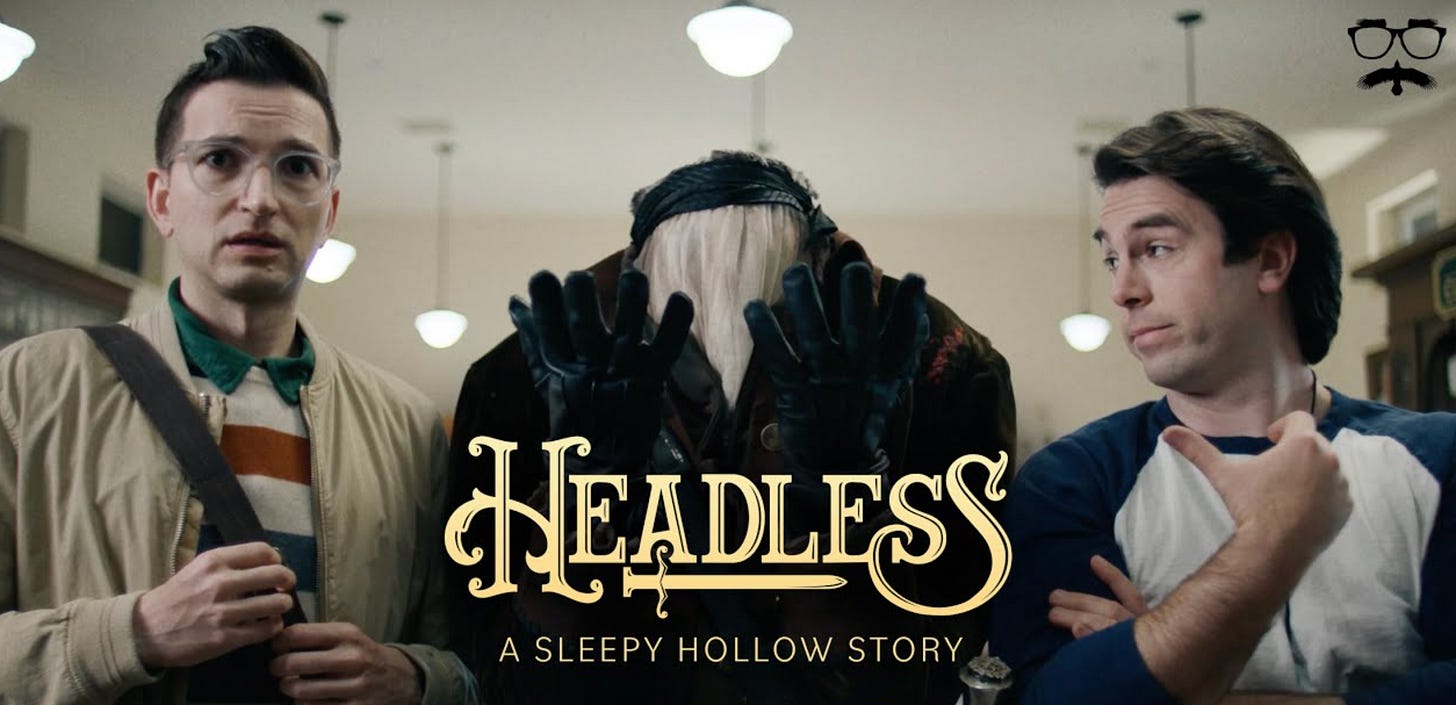

The immediate impulse for this conversation—beyond a desire to remind you that Quibi is a thing that happened—was the launch of Headless: A Sleepy Hollow Story, which came onto my Twitter feed via Lizzie Bennet Diaries star Mary Kate Wiles, one of the series’ stars and producers (and a Twitter mutual since my coverage of LBD). A take on Washington Irving from Shipwrecked Comedy’s Sean & Sinéad Persaud, the series—which debuted its penultimate episode this week ahead of a Halloween finale—is the latest crowdfunded, historically-driven web creations from this collaboration, and is without a doubt their most ambitious. It’s a charming reimagining of the story, with the Horseman as an amnesiac roommate in search of their true identity, and Ichabod and Co. as a group of mystery solvers scrounging up “heads of the week” who are able to come back to life on the Horseman’s body in each episode. And yet despite a successful Kickstarter campaign for their largest budget yet, the series has struggled to find an audience outside of their existing fanbase, with none of the sense of “virality” that drove those early webseries success stories.

However, the current state of the webseries is something that’s been on my mind since I “retired” that webseries content out of my Intro to TV course sometime in 2016 or so, shifting instead to focus on streaming distribution, and I return to it each year when I lament the Emmys continually nominate primarily derivative web content based on existing scripted/unscripted TV shows in their “Short Form” categories. Christian wrote his aforementioned book while developing the nonprofit Open TV platform for intersectional web storytelling, and there’s no question the comparatively low production costs of short-form content has helped new voices bring their content to audiences. But outside of those types of incubators for creative production, this type of short form content was never adopted outside of YouTube/Vimeo, outside of a rare instance of a show like the first season of Netflix’s Special that I’m honestly convinced Netflix hamstrung with short runtimes in its first season solely to try to rack up Emmy nominations in the aforementioned Short Form categories.

As such, when I saw Wiles’ tweets about Headless on my feed, I wanted to hear more about what it’s like creating a webseries in an environment where I highly doubt my current students would even know what it was, let alone perceive it as a critical part of the larger television landscape. The responses I received to my questions from both Wiles and Sean Persaud paint a clear picture of a form of creativity that remains viable as a crowdfunded proof of concept for producers’ abilities, but must now navigate a system actively antagonistic toward its liminal place within media production.

“We want to make a thing so let’s make the thing and share it”

Nothing has changed about the basic logic of the webseries production in the past decade: through the combination of crowdfunding and YouTube, creators who have an idea have the capacity to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of industry and appeal directly to their audience, in the process achieving the satisfaction of both creating art and seeing it connect with viewers. And for an established group like Shipwrecked, cultivating that fanbase over nearly a decade has allowed them to scale up that production, with a budget of $250,000 for Headless, producing something that certainly looks like something you’d see on a streaming service.

But making an upscaled version of the webseries—more professional, longer episodes, bigger budget—has always been a financially risky proposition. While Persaud and Wiles both primarily frame Headless as a labor of love, and as a demonstration of Shipwrecked’s skill in an effort to pitch themselves as writers/producers to those gatekeepers they’re bypassing, part of why upscaled webseries content never broke out on YouTube is that the financial structure has always been untenable for this type of “content.”

In 2014, I spoke with now disgraced YouTube star Shane Dawson as part of his participation in Starz’s The Chair1, and I asked him about how viable YouTube was for feature films or other premium content, and after he said no he said the following:

“At some point, though, maybe—I think in the future the ads will be television quality ads, and we’ll all be making enough money where we can be putting up really high quality shit, but right now it just doesn’t work that way.”

But this future never materialized once streaming television emerged to place YouTube in a no man’s land between social media and television, a platform not fully comfortable as part of either conversation—just look at the failed launch of YouTube Red, now YouTube Premium, which tried to engage viewers with scripted content similar to Netflix et al but eventually abandoned this strategy in favor of influencer-focused unscripted fare.2 They simply don’t have a clear grasp on what the platform represents, which has hampered them both in launching a streaming service and in garnering ad rates even close to broadcast television. It’s also meant that rather than webseries creators growing the scale of their work within YouTube as a platform, those who weren’t lucky enough to instantly score development deals were largely forced to abandon the mode of production in favor of angling themselves toward more traditional film and television production.

“It’s just a constant feed of seemingly random videos being broadcast to a bunch of glazed eyes”

But despite this, YouTube has nonetheless remained a platform where a project like Headless could serve Shipwrecked’s basic goals of demonstrating their storytelling capabilities and connecting their art with the largest audience possible. And for a time, the rise in longer videos on YouTube seemed to create a space for producers to go beyond the 3-5 minute micro-content approach that was considered necessary a decade ago, with the average user no longer balking at a video just because it was “long.”

The current climate, though, has created a new problem even for producers who accept that YouTube is not going to be a viable platform financially. As YouTube works to try to compete with Tiktok and other social platforms, its algorithm is increasingly trying to drive creators toward producing content—an important word here—that matches with shifting viewing patterns. From Persaud’s perspective, they are running into how YouTube’s algorithm is working against them on multiple fronts:

“You can’t just be subscribed to a YouTube channel anymore. You have to receive notifications and check in. That YouTube channel has to have a certain amount and certain type of engagement to get promoted in the algorithm. That YouTube channel has to make “Shorts” in order to get promoted in the algorithm. Or else you spend a quarter million dollars going all out making the calling card that you’re betting everything on and it ends up being even better than you imagined, and no one watches it.”

In other words, even if YouTube ads had become more lucrative in the intervening years, making long-form content remains a huge risk for smaller accounts that don’t have huge built-in audiences, as the algorithm is actively working against accounts that aren’t simultaneously embracing the type of content YouTube feels it needs in order to compete with Instagram and TikTok. And as Wiles has worked to try to spread the word on other social platforms, they’re running into similar issues:

“I do think the TikTok-ification of social media outlets in general has made it difficult for groups like us who make longer-than-one-minute horizontal narrative content. Here I am trying to cut up our show into bits and pieces to put on Reels/TikTok in hopes that that will encourage people to watch it. But that’s not what we make, and it isn’t what we want to make.”

Given all of this, Wiles admits she’s “not exactly sure what we’re thinking making high quality episodic content for YouTube,” but it showcases how YouTube’s promise as a platform for creators hasn’t died despite those creators feeling forced to fit themselves into a box shaped by YouTube’s competition with TikTok and Instagram. Even if TV-level ad revenues never manifested, and even if the algorithm is actively working against creators that don’t fit into a certain box, there’s always the potential that the thing you make breaks out, discovers its audience, and creates a reputation that carries with you into a professional career.

“But then we look at that view count and it just doesn’t compute”

The question, then, becomes how you market a webseries to audiences within this climate. While Persaud acknowledges that the historical bent of Shipwrecked’s content may have positioned them as niche in the past, he sees Headless as a property with inherent mainstream appeal:

“This time around, with Headless, I think the existing IP as it were, and general subject matter, is incredibly accessible. It’s a funny, spooky, whimsical, Halloween set mystery. People love this stuff. So why aren’t people watching it?”

This has always been an existential question when it comes to media, but there’s no question it’s particularly apt in an era of Peak TV, where the sheer volume of options within television has become overwhelming without even considering how platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram are competing for audiences’ attention. And Headless no doubt finds itself trapped between those spaces, angling for the same audience as shows on Hulu or Peacock, but existing on social platforms where they have to compete with the aforementioned algorithmic forces therein.

From Wiles’ perspective, though, the audience Shipwrecked has managed to find doesn’t seem to be the same as the audience they’ve found for past projects like 2016’ Edgar Allen Poe’s Murder Mystery Dinner Party:

“In terms of audience, I think so much has changed. So far as I can tell, besides our Shipwrecked die-hards (who we love and are so thankful for!) the audience for Headless seems largely like a new batch of folks who’ve come over from some of our D&D cast crossover. It doesn’t feel like the same people who were watching Poe Party when it came out in 2016. And I don’t exactly know why or what to attribute that to.”

Here we discover the complexity of the question of the webseries’ place within cultural consciousness. On the one hand, I have no doubt younger audiences—let’s say college-aged, as I come to this through the lens of my students—don’t really understand what a webseries is because the algorithms they rely on aren’t directing them to this content, and they have no need to seek out alternatives to “traditional” television in a streaming era where the breadth of options is already beyond their comprehension. But as Wiles notes, it seems like the audiences that were falling into watching webseries content six years ago aren’t coming back either, at least anecdotally. While it felt a decade ago that being a “webseries fan” was something audiences used to distinguish their taste from the mainstream, the slowdown in production and the rise of so many other options seemingly displaced this trajectory.

“As long as someone with some ability to hire us can see the quality of the work that we do”

Despite all of this, both Wiles and Persaud are adamant that they are fortunate: through the support of their existing fans, they were able to make the thing they wanted to make, and are incredibly proud of the final project. But Wiles also acknowledges that this is far from sustainable:

“The only reason we’re able to make such high-quality stuff on these budgets is because everyone on our team is working for way under what they should be paid. And we don’t want to always be doing that. We didn’t pay ourselves anything for Headless. We CAN’T keep doing that. We can’t work for free for years on another project in the future. We have bills to pay. So…not exactly sure what we’re thinking making high quality episodic content for YouTube [laughs].”

As noted, though, the possibilities of YouTube as a platform remain such that there’s a clear incentive to try, provided you have the resources. As Persaud notes, “the best hook is ‘millions of people are watching this show,’” and thus the memories of the viral webseries era foregrounds the potential that the show garners a huge audience and generates buzz that can translate into a stronger position within the industry.

The question is whether it’s even possible for a webseries as a format to connect in this climate. If we return to Quibi—which you may well have forgotten about again in the 8 minutes since you last read me talk about it—there were no doubt many reasons it failed, but is it possible that people don’t actually want to experience a narrative in “quick bites” ten years after the format’s peak? While longer than traditional webseries episodes, Headless’ installments are still definitely robbed of a more complex sitcom structure—I concur with Wiles and Persaud that the show looks like something on a streaming service, but there’s still something about episodes that seem to stop before they’ve really started that feels unsatisfying, through no fault of the creative team involved. Self-funding or Kickstarting an outright 20-minute, 10-episode webseries would be pure folly, but the “compromise” of the webseries may have over time become a liminal form trapped within the expectations of an audience with far more “content” at their disposal than they could ever hope to consume.

When the finale debuts next week at the conclusion of a week of events planned by the Shipwrecked team, Headless will become a 10-episode binge, and I have every reason to believe people will continue to stumble upon it. While Shipwrecked hired a marketing team that helped them get early coverage, the nature of algorithms is that people will be constantly discovering it, including some of those webseries viewers from a decade ago who may not even know people they recognize are still working in this form.

But as Persaud notes, “we’ve been really happy with our publicity team, but we just don’t have the money it takes to really saturate the landscape - or any idea what the landscape should be.” That uncertainty is why a project like Headless feels like it’s floating in the online ether, a polished narrative trying to either find the audience that can make it a hit, or hope that someone with the power to help Shipwrecked make more things like it is able to find it.

Episodic Observations

Special thanks to Mary Kate Wiles and Sean Persaud for taking the time to share their insights on this topic. The Headless finale debuts on Halloween.

I watched the first episode of Amazon’s The Peripheral, which I thought was interesting, but then I ran into the fact it was 70 minutes long, and it was late, so I didn’t follow the cliffhanger to watch the second episode. I’ll probably get to it later in the week, just in time for there to be a third episode I don’t have time to watch right afterwards, but overall I’m intrigued by the worldbuilding.

I also worked my way through the first two episodes of Freevee’s High School, Clea Duvall’s adaptation of Tegan and Sara’s memoir, which I’m enjoying for reasons beyond its embrace of its Canadianness (but that’s a huge plus, admittedly).

Even if you’re not normally inclined toward horror as a genre, I highly recommend watching Barbarian on HBO Max this week while knowing as little about it as possible. It’s absolutely disturbing, but it really creates space for you to both experience and then deconstruct horror tropes in ways that even non-fans can appreciate.

I will still to this day derail any and all conversations to unearth my obsession with The Chair, but you can just go read my A.V. Club piece I wrote after the finale.

I always ask my students if they even knew Cobra Kai existed before it landed on Netflix—the answer is always no.

I will also throw in High Maintenance. It had the fortune of being picked up by HBO (and the original web series is housed in HBO) but I originally enjoyed it on Vimeo and even paid to help them make more episodes. That’s the only web series I have watched but Headless looks good! Very interesting insights on the form. Maybe after consolidation of these corporations and the Disneyification of “content” viewers might return to the old form.

P.S. I watched Cobra Kai on YouTube after subscribing to YouTube TV for a month.

Friends mocked me for signing up for YouTube Red just to watch Cobra Kai when it came out and then I forgot to cancel it for like 9 months afterwards but I'll just pretend that money went to producing more Cobra Kai.