Week-to-Week: From Story Sync to GetGlue—Historicizing the rise and fall of Social TV

An Episodic Conversation with Social TV author Cory Barker

One of the things about being a media scholar is that you’re always on the job: no matter what type of media you study, it is constantly changing, meaning that the questions you’re asking and the answers you’re getting are a moving target.

As a researcher, though, you can’t write about everything: we might observe twenty potential research ideas, tweet about fifteen of them, and use ten of them in our classes, but we’re lucky to write about one or two, especially if they’re amorphous concepts that shift in any given moment. Between blog posts—remember blogs?—and conference presentations, my own academic career is littered with case studies I was consumed with enough to write about in a given moment, but which were simply infeasible to turn into something more substantial alongside the other research I was working on during those periods.

I provide this backstory to explain how thrilled I am to see Cory Barker’s new book Social TV: Multiscreen Content and Ephemeral Culture released by University Press of Mississippi last week. Cory is a long-time friend and collaborator in addition to being an Assistant Professor at Bradley University, and is also someone who was with me in the trenches online during a transformative time to be teaching about and researching television.1 And while my own reflections on this era are captured by essays and blog posts to varying degrees, I knew how vital it was that someone capture the moment when social media interaction felt like it was going to be the future of TV, especially given how distant that moment feels in 2022.

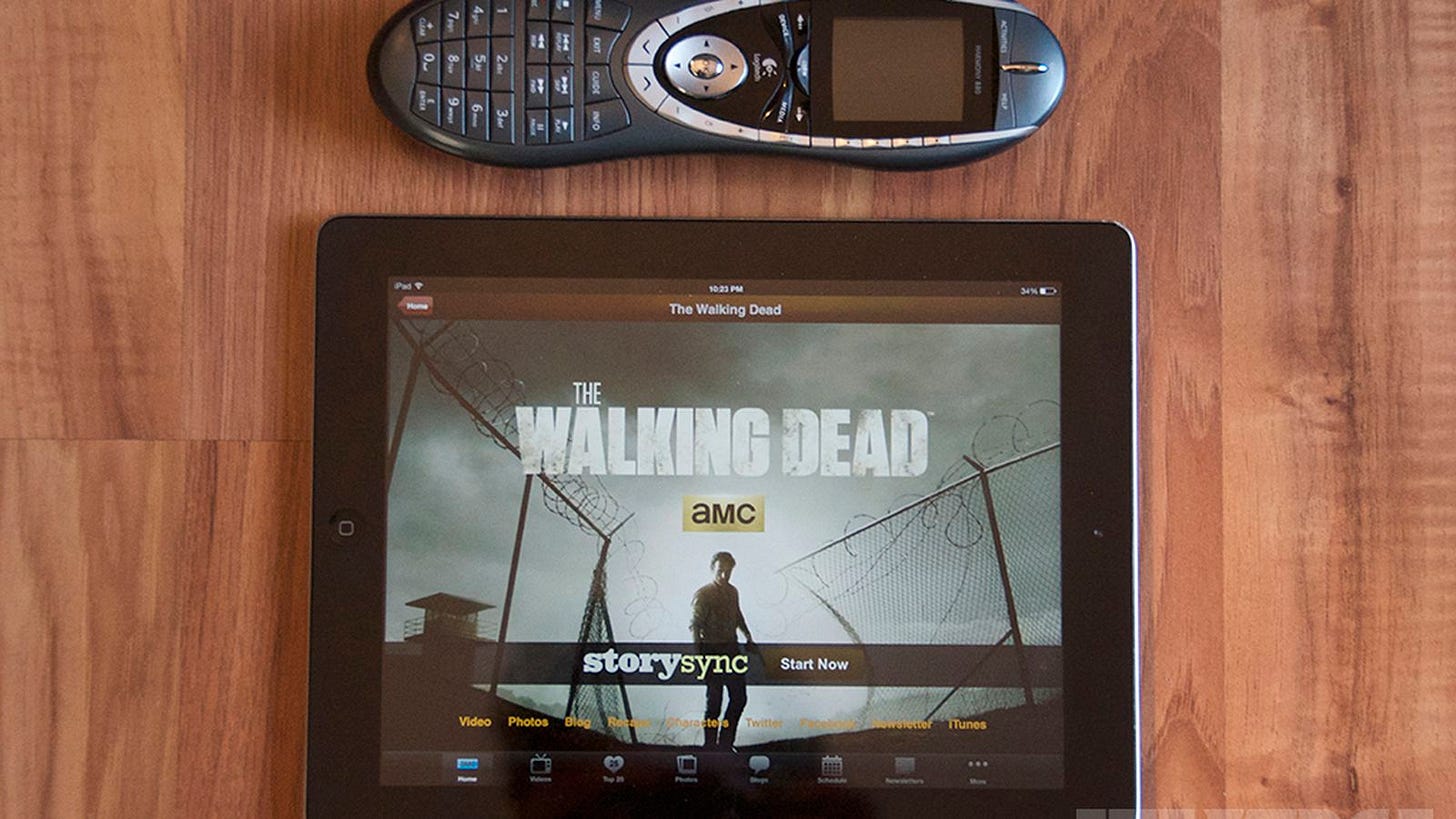

And so I was thrilled to learn that Cory’s dissertation would be evolving into this book, which constructs an “ephemeral historiography” of experiments like AMC’s “Story Sync,” the rise of check-in apps like GetGlue, the success of #TGIT, the (d)evolution of channel/network Twitter voices2, and the false promises of Amazon’s “Pilot Season.” While the introduction frames the project within existing academic literature, anyone who lived through this period of time as an Online Individual will find a lot of great, accessible perspective on that moment.

And while I could have excerpted a piece of the book here, I thought it would be more productive to talk with Cory about how this came to be the area of research he focused on, which parts of the book resonate most with him, and also which parts of the book resonate most in our current moment. The conversation inevitably turned a bit meta in terms of Episodic Medium’s own place within the dynamics of Social TV, so I’m really interested to hear subscribers’ feelings about this subject, and hope you’ll join the discussion in the comments before heading off to pick up a copy of the book yourself.

Myles McNutt: Cory, I want to start by asking if you remember the point when you realized Social TV would be the subject of your dissertation and now book. Was there a particular moment that took this from a thing you were naturally observing as an Extremely Online individual to what it eventually became?

Cory Barker: First of all thanks for having me here to chat about the book and a topic that you are quite the expert in as well.

While I had already been interested both personally and professionally in the kind of ad-hoc communities that were forming around live-tweeting and TV chatter as early as 2009, it was in late 2012 when Nielsen announced its “Twitter TV Ratings” that I started thinking differently about the subject. It took Nielsen nearly another year to officially roll out that measurement tool, but the announcement signaled to me that various forces within the media industries had decided “OK, this Twitter stuff could be valuable.” Before that, networks had experimented with live-tweeting and hashtags—CBS of all companies did a couple of “Tweet Weeks”—and upstarts in Silicon Valley were pumping up the potential of synchronized, multi-screen “experiences.” But Nielsen’s efforts are always a compelling, reactionary indicator of what studios or networks or advertisers value, if even temporarily. At a time when established data points like overnights and DVR ratings were showing increased erosion of live viewing, the Twitter TV Ratings felt like a late push to legitimize the collective potential of appointment viewing with multiple constituencies: viewers, Hollywood executives, and sponsors.

MM: So this really registers why I think this book is so important, because it’s capturing a moment that it really feels like we’ve lost perspective on. I reflect on it often when I’m teaching my TV class, which remains based on the foundation I built lecturing an Intro to TV course in Spring 2013. And so it had a significant Twitter component, and really built itself on this idea of disruption (a key term you’re thinking about) and the industry’s response. And I had that Twitter lecture in there until like 2017, at which point I came up for air and realized that my students just had no conception of that relationship between Twitter and the TV content they consumed.

When you talk to your own students now, and as you were working on the book, how do you find they understand the period you’re discussing?

CB: It’s foreign to them on multiple levels. There’s a disconnect with Twitter, a disconnect with live TV, and then a disconnect with the relationship between those entities. Just this past semester, I tasked students in one of my journalism courses to research me online to practice interview prep, and many of them were hung up on the fact that I had sent 12-15 tweets during the Oscars telecast. They were embarrassed for me! I tried to explain how “normal” that was—especially for this particular Oscars—and it just did not register.

The evolution of your class speaks to how the project evolved as well. When I first started writing research papers about live-tweeting, check-in companies like GetGlue and Viggle, and the two-screen products like Story Sync, they were being positioned as, if not the future of television, at least one important future of television. By the time I got to the dissertation stage, and certainly by the book stage, the industry had almost entirely moved on. It was interesting to reflect on how even academic research on “new” media or developments can get caught up in the same kind of hype that it seeks to interrogate. Watching that happen in real time helped me crystallize the ways in which these waves of hype build, crest, and completely dissipate. Talking to students about the era helps underline that too. The peak of this micro-moment (let’s say 2011-2015ish) happened when they were in middle school, so it is truly history to them.

One important qualifier to all this is that, relatively speaking, so few people were live-tweeting Community or using Story Sync. We know that so few people use Twitter at all. The book tries to underline that Hollywood and Silicon Valley tried to position this activity as “normal” fan or viewer practice in an effort to legitimize and monetize it. In that regard, it’s not surprising that our students are confused when we talk about all the posts about Glee, which makes it all that much more important to discuss them today.

MM: First of all, how dare you remind me that our students were in middle school when this was happening.

But second, I agree that all of this has been memory holed by society at large, so I’m wondering what’s the one case study in the book that you really feel should be remembered more than it has been? You frame Social TV as an “ephemeral historiography,” and so if you absolutely had to capture one of these experiments for posterity, which would it be?

CB: You’re asking me to pick between my favorite discarded children! Twitter plays such a central role in the story, but there are still notable remnants of those experiments today, from live-tweeting major events to the “weird” shit-posting companies like Netflix do to annoy us every day.

I keep coming back to the check-ins because that feels like the most “you had to be there” phenomenon. For a brief time, certain segments of the Valley and the TV industry thought that digital stickers—and in the case of GetGlue, mailed hard-copy stickers—could constitute valuable fan engagement and potentially compete with platforms like Twitter and Facebook. While it is important to remember that check-in users (like myself!) did get some enjoyment out of the platforms, and even got together to essentially break the system for more rewards, it’s hard not to see the stark contrast between the hyperbolic promises sold by executives and the very basic rewards offered in reality.

The three companies I focus on (GetGlue, Miso, and Viggle) were involved in so many rebrands, buy-outs, and failed mergers—even during their “successful” periods—that it reflects how quickly the hype fizzles out in these transitory moments. And yet, by the time I got to the end of the dissertation and the book stage, I started to see people share their TV Time check-ins and track their film watching on Letterboxd. Clearly, there’s interest in a platform that blends social media with a logging of media consumption, but the additional value proposition of liveness or synchronized conversation isn’t there.

Check-ins are also a great example of the role the trade presses play in building hype and discourses about disruption. The “Most Checked In” charts (it just rolls of the tongue) were not exclusively a GetGlue creation; they were created in partnership with Ad Age, and then reported on by your friends at TVbytheNumbers3 and the Hollywood trade establishment. Those charts both legitimized the check-in as a phenomenon but also functioned as an indicator of popularity among audiences, who then used them in online debates about cancellations and renewals. For the check-in companies, those discourses helped pump up a mini-industry desperately seeking additional capital investment. For the networks, they helped (in theory) buoy interest in live TV. But it’s essential to remember that they also helped the press sell a narrative about disruption and the future of TV, from which all of those publications benefit.

I said this on Twitter the other day, but it’s hard not to think about those check-in charts when we see reports about the most watched shows in streaming. There’s immense skepticism within the industry, including among reporters, that any of the data is legitimate. But it still gets retweeted and reported on because there are so many constituencies that need it to be legitimate. It’s a bit of a shared delusion, and the check-in example shows that folks will go along with even relatively small data points if they indicate growth or expansion.

MM: I suppose the inverse of this question is which of your children you actually discarded: in a book about forgotten toys, were there any you had to leave on the cutting room floor for one reason or another?

CB: I cut a bunch of experiments that illustrated similar ideas covered in the book. The X Factor and The Voice were both pretty invested in live-tweeting and multi-screen content early on, and HBO and Showtime had failed Story Sync-esque products, just to name a few examples. I could have told a longer version of how Twitter embraced its role as a partner to TV networks to try to bring more advertisers to the platform. There were countless blog posts and recommendations for showrunners or actors on how to live-tweet effectively or what hashtags to use. But as these things go, it was actually hardest to find a stopping point. The conclusion addresses Facebook Watch and Twitter’s “live video” initiatives that mostly flopped but represented a natural evolution of those platforms generating value off of other companies’ content for years.

Even at the final stages it was hard not to include more about the pandemic, which revitalized some of the core promises of Social TV because so many more people were at home watching more TV and looking for community. But ultimately, I thought it was important to recollect on the 2010s as this period of transition, even though we see the threads of Social TV today, both on the industry and consumer side.

MM: As someone who also finished a book during the pandemic and DID make it my conclusion, I understand that struggle. I’m curious to hear you expand a bit more on your experience observing the COVID era of Social TV: you note a blip in audience connection to the principles of this era, but was there similar movement on the industry side? Or had they simply moved past it?

CB: You’re braver than me. I had to keep the door closed! I think we saw the re-emergence of the principles during the early stages of the pandemic during lockdown. On the audience side, we saw how the captive lockdown audience magnified the ways in which Netflix captures attention in these suffocatingly short bursts of hype. ESPN’s The Last Dance likewise benefited tremendously from people being at home desperate for “new” content and conversation.

But the industry side was there too. We saw how folks watching “live” together via Zoom or FaceTime was quickly corporatized by the Teleparty app or internal watch-along features on Disney+. Another notable example came with the films (The Invisible Man, Emma, The Hunt, The Way Back to name a few) that were in theaters in early March 2020 and quickly shuttled to “premium” VOD. Universal pushed some “live” Watch Parties where directors would live-tweet behind-the-scenes anecdotes and answer Qs, or in the most random example, hire Retta to riff during her viewing of Invisible Man. ComicBook.com hosted a bunch of MCU Watch Parties and the Russo Brothers showed up at least once. Those experiments demonstrated that the industry is still invested in eventizing the at-home viewing experience, but the fact that they haven’t continued probably tells us that it’s not a priority.

MM: I guess that’s kind of the ultimate question: was this ever really a priority for the industry? The press releases certainly claimed it was, and it certainly felt like it was in the trenches, but do you think there was ever a single moment where the industry believed that this was the future, even naively?

CB: For veteran networks and studios, it was a way to square a few circles. By 2011 or 2012, there was enough evidence showing that people loved to be on a device while they watched TV and enough evidence suggesting that, very soon, on-demand streaming would be the primary way young people watched (non-sports) television. Ideally, Social TV products offered a kind of solution to both data points: give multi-taskers an ad-driven space to be and a reason to be there in real time. Did AMC think Story Sync would prevent enough people from watching Walking Dead on-demand on Monday? Probably not, but I think people there hoped it would be a great way to shape the experience of some of the most active viewers and make some money along the way.

Perhaps it’s also easier to be skeptical now that these initiatives mostly failed and the industry has committed so fully to streaming. The most successful example of the era—Scandal and #TGIT—happened after Netflix started with originals and all-at-once distribution. And if you look at the executive commentary from Upfronts or TCA and the press coverage, the tenor wasn’t “this is a very particular case,” it was “look at what you can still do, and on network TV no less!”

And we still see the threads of this first iteration of Social TV in our hyper-fragmented, on-demand landscape. Award shows are still desperate to go viral. The Will Smith-Chris Rock confrontation illustrated the power of the relationship between live TV and Twitter as people were desperately trying to figure it out if it was—to use wrestling parlance—a work, a shoot, or work that became a shoot.

The evolution of digital distribution has generated new incentives regarding how and when to watch. It’s less liveness and more immediacy. You have to watch the new Stranger Things or MCU episodes as soon as they're out. That inspires people to communicate about the shows or episodes in a slightly different way. My students have actually helped my thinking in that regard as I’ve encountered their responses to ST4 not via live-tweets but “live” (whenever they’re watching) reactions on IG stories and in Discord and in flooding those spaces with post-release memes. To an extent, something like “Running Up That Hill” suddenly speeding up the song charts is a fundamentally modern Social TV phenomenon, where the reaction and activity to a show on social platforms has an impact on other media. It’s different from 13 or 22 weeks of real-time engagement with a show in 2012, but there are still ways for companies to leverage attention. It just happens in faster, and more siloed, ways now.

MM: I enjoyed the reactions to “Running Up That Hill” where people wondered how this didn’t happen with *insert song from past show* and the truth is that TV is just doing the same thing it always has, but TikTok happened, and Spotify happened, and Billboard changed its chart metrics to reflect those changes.

CB: Absolutely. Television is part of a larger, more complex, and more interconnected ecosystem now, especially when we’re talking about the short- or long-tails of hype and attention. The most popular shows reveal that faster and more visibly—I keep thinking about how songs used on The Dropout deserved similar chart success—but the industry is still willing to respond or create frameworks that enable social media-driven triumphs.

Can I flip this to you for a moment? So much of the hype for Social TV initiatives back then felt connected to, or even extensions of, the kind of criticism-led conversations happening on the Television Without Pity boards or in the comments of Sepinwall’s Blogspot and the A.V. Club reviews. In one form or another, these companies were trying to leverage the very visible explosion in chatter online about TV. Now that you’re keeping that kind of conversation alive here, do you get the sense (whether through your metrics or just a vibe) that people are coming to open reviews and comment very quickly? A few days later? How does that appointment viewing and reading seem to track thus far?

MM: I’ve written before about the experience of trying to figure out how to cover Orange Is The New Black episodically back in 2013-2015, and the reality is that was a matter of balancing the conversation happening in the comments with the SEO-needs that would position the site financially. And so in some ways, doing this as a subscription model frees us from those needs, and the timing of the reviews is less important.

But it’s also a complete crap shoot. Donna’s Better Call Saul reviews are getting lots of night-of conversation, but that’s the only linear show we’ve been covering, and there seems to be very little agreement on when people are watching weekly streaming releases. In the case of For All Mankind, for example, should I publish the reviews at midnight Pacific when Apple’s embargo technically ends, given they go up six hours before that? I ended up doing noon the next day, but by what logic? With Zack’s reviews of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, we settled on 2pm on the day of based on my belief that would catch the people who have time to watch on the day of release alongside people in Europe who would watch in the evening, but was that actually logical?

I expect that for shows with appointment lineages—Saul traces back to Breaking Bad, while House of the Dragon will draft off of Thrones—there’s a clear desire for “I WANT TO DISCUSS THIS RIGHT NOW.” But I do wonder whether the average reader of an episodic review is necessarily that invested in that type of dialogue, or if the people who wanted that have already basically pivoted to Reddit as their primary source of social engagement around their TV viewing. But I’m sure that the 750+ paying subscribers to this Substack all watch TV entirely differently, and thus creating space for them to discuss it is really about threading that needle. And I guess they’ll have their say in the comments of this newsletter.

And as long as we’re getting meta, I’ll end with this: how has your own relationship with Social TV shifted in recent years? As noted, the pandemic had its own impact, but a lot has obviously changed for you personally that I feel would inevitably reshape your relationship to these things as well.

CB: Your explanation underlines how some of the conversations that were happening in very public forums, from free comments sections to social platforms, have now migrated to smaller communities with varying degrees of privacy. Whether we’re talking about a growing paywalled Substack commentariat or group chats, the dialogue and jokes are still there but with time lags or more polite “Hey, did you finish Righteous Gemstones season two? Did you even start it yet?” messages.

Those questions are definitely reflected in my experience too. On the one hand, between the pandemic, marriage, and now a child, very few television shows have remained appointment viewing. While it helps knowing that everyone who’s into this stuff feels behind in some way, it also sucks to say, over and over again, some variation of “No, haven’t seen it. Probably won’t ever see it.” Like all Millennial parents, I just end up replying with something about Bluey.

But on the other hand, I’ve spent the last few years falling deeply in love with soccer, where so many of the European league games align with my earlier scheduled and mid-day childcare responsibilities. When I’m watching matches, I still tend to follow conversations on Twitter among the writers and posters I admire—shout out Grace Robertson—even if I’m not sharing as much because I’m still figuring out the tactical flow and strategy of the sport. The same thing is true for the major award shows or pro wrestling events, some of which I watch exclusively for the chatter. So even though a lot has changed about how we collectively watch TV and how I personally watch TV, there’s still a desire for live, semi-synchronized conversation, just like the popularity of Letterbox and TV Time illustrates a desire to track and share in a social platform-like space.

If you’ve read this far, then you’re probably at least mildly interested in Cory’s book, so head to the University Press of Mississippi website or the online retailer of your choosing to order a copy.

He focuses on HBO, but honestly Amazon and Fox’s annoy me the most.

Cory’s phrasing here reinforces how long we’ve been in the trenches together. If you need an explanation on my relationship with TV By The Numbers, go read about my feud with the Cancel Bear in this piece at The Atlantic.

This is a great conversation, and I am hyped to learn more about this period in television that mostly passed me by (because I am old -- I remember thinking how cringey these second-screen and social things were, but was never tempted to join in). OTOH, I certainly see these night-of engagement things still drifting past my twitter feed, like actors or showrunners trying to get hype going about livetweeting episodes (and trying to navigate the bi-coastal timezones while doing so). I follow Shaun Cassidy and Alison Tolman, just to name a couple of randos, and they would do this for New Amsterdam and Emergence (IIRC). That makes the livetweet thing seem directed at olds like me, even if I actually have no interest in following along that way, so I wonder who the audience is supposed to be. Maybe it's really the other way around -- trying to get these folks' social media followers watching night-of, rather than giving watchers a way to engage.

As a 55 year old, I suppose I'm just grateful I've been part of any of this at all. I will say that AV Club was hugely important to my tv viewing/commenting/engagement for many of the reasons mentioned in your discussion. Likewise, I am now obsessed with Letterboxd for similar reasons. That said, Twitter still remains an excellent source of amusement and connection for the reality shows I can't help but love.

All to say, that social

TV remains quite important to me and the communities that have flourished because of it. But again, as an old, maybe that's more true of Gen X than I realize?