Week-to-Week: Why an inclusive take on Project Greenlight was doomed from the beginning

Diversity and inclusion and a frenzied, filmed production process don't mix

Week-to-Week is the (mostly) weekly newsletter of Episodic Medium, where I reflect on television and other media. To get future newsletters and learn more about the show’s we’re covering weekly for paid subscribers, sign up below.

If you knew me in 2014, you heard about Starz’s filmmaking documentary series The Chair. After getting screeners and attending the show’s TCA panel, it was all I could talk about, and my review of the series finale for The A.V. Club documents my long obsession with producer Chris Moore’s attempt to turn Project Greenlight into a competition series.1

The TL;DR version of this coverage is that I was fascinated with The Chair’s inability to tell the story it claimed it was telling. The show—which featured two very different directors making their own versions of the same script—positioned itself as a filmmaking experiment that would tell us something profound about how the role of the director shapes how scripts connect with audiences. But because they allowed the scripts to be changed dramatically, and because the actual competition component was busted the second they pit a YouTube star with millions of followers against an indie filmmaker with almost zero, the “thesis” of the show ended up being about the tension inherent in making a movie under these circumstances. And while that created wildly compelling reality television, it highlighted how there’s just no way for films developed and produced under these circumstances to shed those circumstances, always for worse.

I offer this preamble to say that while I didn’t initially tune in when Project Greenlight returned to HBO—well, Max—earlier this month, I couldn’t help but notice Friend of the Newsletter Kathryn VanArendonk’s tweets about it, which were following up on her piece at Vulture that went up last week. Specifically, she highlighted the fact that in its return, Project Greenlight has shifted to a directly activist stance after having previously only featured male filmmakers:

“Throughout the season, executives from multiple invested companies explain that their primary goal is to enable and support the career of the season’s chosen director, a quiet Black woman named Meko Winbush. Project Greenlight is about building a pipeline of young, driven directors. It’s about finding the best person for the job and making sure to look outside the usual list of white male candidates. It’s about change.”

I want to state upfront that I think the mission of diversity and inclusion embodied by the new Project Greenlight is a good one, and an important one at a time when studios—including Warner Bros. Discovery—are actively abandoning established pipelines for marginalized groups to gain entry into the film and television industries. But wedding this to the process of Project Greenlight is a fundamental miscalculation, where it sounds like a great fit so long as you actively lie to yourself and the filmmakers involved about what you’re going to ask of them. I understand how this happened: I also remember Effie Brown’s infamous showdown with Matt Damon during Project Greenlight’s last reboot, and so I can totally see how lead producer and mentor Issa Rae would choose to pretend this wasn’t a terrible idea.

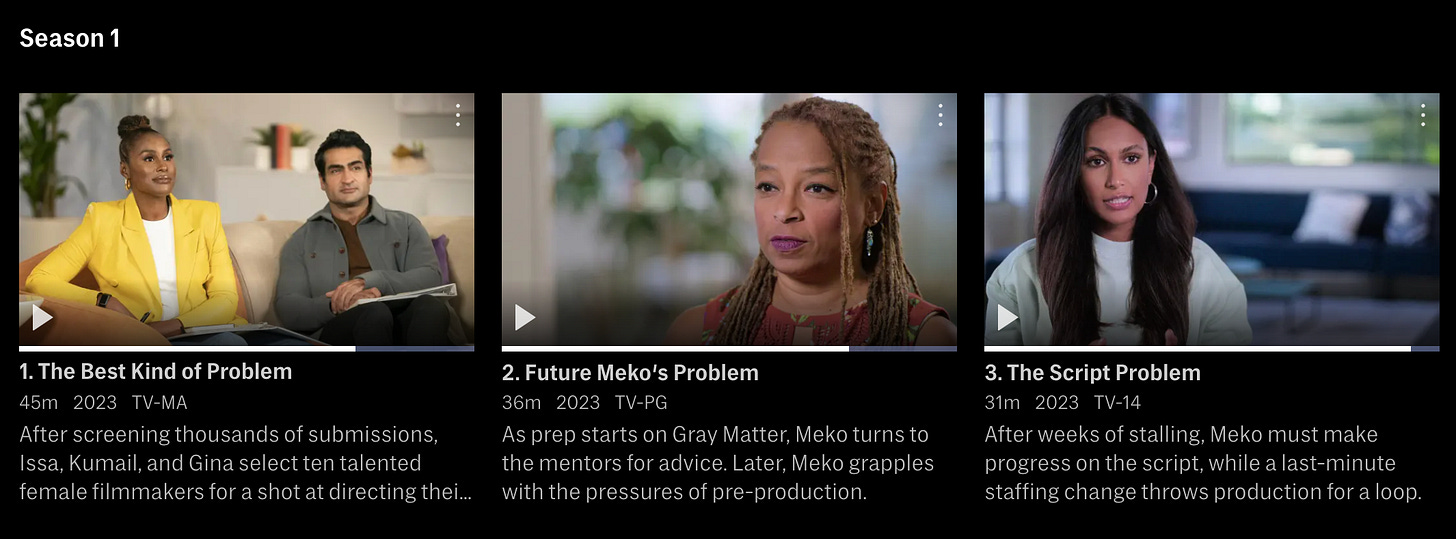

But the deeper you get into the process of making half-baked science fiction film Gray Matter, the more the show’s desire to create change reads as folly. As Kathryn details, nothing about the process depicted in Project Greenlight is conducive to the show’s message of change. The mentors—Rae, Kumail Nanjiani, Gina Prince-Bythewood—are mostly absent and largely ineffectual. The production companies involved—Rae’s Hoorae and Catchlight—know what it takes to make a movie or TV show, but have no way to reconcile what needs to be done with the underlying goal of uplift and inspiration. But most critically, I would argue, they commit the cardinal sin of making a movie as part of a reality TV show: they hired someone for a theoretical job instead of the actual, frankly terrible job buried beneath this amazing opportunity. And the result is a quagmire of best intentions where the fiction of the show’s premise risks undermining their stated intentions.

Given the process of how Meko—they call her by her first name so often in the documentary, it seems unnatural to not do so here—was selected as director, it’s funny to me that they would market Gray Matter as “from the winner of Project Greenlight.” This implies that she was the victor in a drawn-out, in-depth process which would signal the film’s likely quality, but what we saw was something closer to the selection for a fellowship program. Yes, Meko beat out thousands of applicants, but we don’t really have a lot of insight into the process: we see very little of their directing samples, a few clips of Zoom interviews, and then slightly more footage during the final callbacks where they were asked to direct a scene from the script. And while the reality show manages to find a few beats of characterization to differentiate our contenders, it ultimately finds none for Meko, who was chosen because she delivered the scene the producers liked the most.

However, this is where Project Greenlight breaks down. If this were a fellowship program, the goal is creating a space conducive to Meko gaining valuable experience and being able to reach her full potential as a director after having spent her career making short films and working as an editor for films and trailers. And while the show’s “mentor” structure gives the impression this is part of their goal, the job Meko applied for isn’t designed in a way that helps someone reach their full potential. She’s not being given the time and resources to execute her vision: she’s being given a half-finished script she didn’t develop, almost no time for pre-production, an incredibly tight shooting schedule, and then the DGA-mandated window in post-production to try to turn it into a workable movie, all while simultaneously being filmed around the clock and forced to narrativize her experience. Oh, and Rae is clear in the premiere that they’re not just trying to get any movie made: unlike past Project Greenlight projects, Gray Matter needs to be “great.”

The reviews are in and it’s not, of course, because it’s basically impossible for a movie produced under these circumstances to be great. But Project Greenlight can’t admit that, and so instead it purports to tell a story about Meko failing to live up to the task in front of her. And to be fair, I shared the frustration of Rae’s production team at Hoorae when Meko continually failed to address script notes and take responsibility for the film’s development, which seemed to extend beyond her low-energy communication style to a lack of creative vision. But the simpler truth is that someone with no experience making a feature is absolutely the wrong person to be tasked with turning Gray Matter into a “great” movie, and the whole situation stems from the show’s mistake of pretending that Project Greenlight is a process focused on quality instead of a process meant to showcase how awful it is to make a movie under such circumstances.

It’s also a process that risks reinforcing criticisms of diversity and inclusion while purporting to support it. There’s a sequence of events during pre-production where the hiring of a Production Designer becomes a flashpoint. Meko interviews Tyler, a white dude who seems to match her energy, and quickly commits to him as her choice in part because everyone involved with the production of the movie is telling her that they need to get this locked in to ensure they stay on schedule. But when the decision reaches Rae’s producing partners, they reveal they actually want the focus on diversity and inclusion to extend to the department heads as well, effectively forcing Meko to interview additional candidates and heavily encouraging her to select Latina production designer Claudia, despite Meko still clearly preferring Tyler.

On the surface, it’s a story about a filmmaker being forced to abandon their chosen candidate in favor of a “diversity hire,” and in her talking heads Meko is very diplomatic but also clear that if not for the producers’ suggestion her gut was going in a different direction. But the “problem” here isn’t that Hoorae is “unnecessarily” pushing diversity into this process: it’s that they weren’t clear on these goals from the beginning. Why wasn’t this clear to their producing partners at Catchlight before they started interviewing candidates, given the time crunch they were under? If Meko had simply been presented with a diverse slate of production designers from the beginning, there wouldn’t have been this tension at a crucial moment within the production, which cost them valuable time even before Claudia (somewhat hilariously) passes and Tyler (definitely hilariously) is hired and then backs out when he realizes he has to appear on camera. It’s a mess Hoorae creates not by choosing to support diversity in their hiring (which, good!), but rather by failing to go into this incredibly pressurized process with clear expectations.

And that is the actual story of this season of Project Greenlight. While I will acknowledge that Meko’s lack of vision for the film and inability to communicate create a degree of responsibility, the central issue is that she was expected to both learn how to direct a film and fix Gray Matter’s script, and at no point does the team at Hoorae really take a step back and wonder if their expectations were the problem. They keep coming back to the claim they specifically hired her because she claimed to be a writer-director, but Meko has said in interviews that she felt misled about the state of the script when she interviewed for the job, suggesting they hadn’t made those expectations clear up front. And if they really wanted someone who could develop the script, shouldn’t they have hired someone whose primary experience outside of directing was in writing (like those with TV experience) as opposed to post-production?

But that would have gone against the purported ethos of this reboot of Project Greenlight, which was picking the most talented or artistic female filmmaker and giving them an opportunity they wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. But the problem is that, if you actually break down what that opportunity entails, Meko was a bad candidate! This doesn’t mean she’s untalented, but she was deeply ill-suited to rapid-paced development of the script, and in her final interview everyone acknowledged she had zero emotional connection to the material or vision for how it would be executed. It’s an objectively terrible interview, and previews all of Meko’s communication issues that are presented as such a problem, but they’re the ones who chose her for the job anyway. They’re the ones who failed to acknowledge that while the choice to focus on an inexperienced filmmaker created an inherently uphill battle given the state of the script and the short timeline, they added to that problem by choosing someone whose demeanor and working style were incompatible with what was being asked of them.

And the problem is Project Greenlight can’t acknowledge its mistake. Gray Matter’s failures have to be Meko’s failures, because blaming the system requires unpacking the inherent incompatibility of diversity and inclusion with the task at hand, and they have no desire to do that. In their effort to push Meko to look at diverse production designers, Hoorae explains that their philosophy is that you hire inexperienced people and then they learn on the job, provided you hire enough strong people around them. They consider this the responsibility of people of color like Rae who find themselves in positions of power, and it’s a noble effort that I support broadly speaking. But they speak of Meko as though she is one of those powerful people simply because they have given her this opportunity, and when Meko insists she’s “not yet at that level” they claim this was true for Rae even during the production of Insecure However, this flat-out ignores that Rae co-created Insecure with Larry Wilmore over a two-year development process, a luxury of time and support that Meko was not offered, and which makes it infinitely easier to balance the immediate needs of production with the existential need for more diversity in the industry. And yet they still place this responsibility at Meko’s feet, because they seem to believe that if they admit there are some situations where diversity and inclusion could function as a hindrance, it undermines the entire principle.

And so in the end, Project Greenlight pivots to telling a story about a movie that everyone agrees is mediocre at best because the marginalized director given the amazing opportunity to direct it simply didn’t work hard enough. The episode descriptions characterize pre-production by her “weeks of stalling” while working on the script, while Prince-Bythewood—easily the mentor most involved in guiding Meko—undercuts her in the end by questioning her commitment to the project during the editing phase (implying she didn’t sacrifice enough when it counted). The message is that Hoorae did an important thing by giving someone like Meko a chance to direct this movie, and it would have worked out if only Meko had stepped up to the plate. But the actual problem is that the process of making a movie like Gray Matter is incompatible with the process of creating space for marginalized individuals to succeed in the industry, and refusing to acknowledge this sells out the filmmaker in order for Rae and her producing team to claim they lived up to their principles.

Episodic Observations

I don’t know what success I’ll have talking to folks, but consider this my commitment to doing a 10-year retrospective oral history on The Chair next year.

Truth be told, I haven’t had the chance to watch Gray Matter yet, since I watched a couple of episodes of Project Greenlight with my boyfriend over the weekend, and he finished the season independently so we’re waiting to watch the movie together. My expectations are…low.

While you could maybe imagine how Rae and Prince-Bythewood could have been more hands-on if not for their respective professional commitments (filming Barbie and editing The Woman King, respectively), it was never quite clear how Nanjiani (also busy filming his Emmy-nominated role in Welcome to Chippendales) fit into the mix. Curious how they imagined him working as a mentor before their schedules all filled up.

If you’re wondering about timelines, the “premiere” event they held for Gray Matter was in late February, meaning that the film sat on the shelf for over four months before its release on Max. Were they simply unwilling to spend the additional budget to extend this, or were they originally intending to release the series closer to that date and then pushed it back?

If you’re looking for Barbenheimer content, I’ve yet to see the latter, so I’m going to wait until the dust settles a bit before wading in. But as a post-script to a previous newsletter about the existential crisis of film exhibition: clearly people are willing to go to the movies, but if you think the industry will internalize the lessons of this weekend successfully, I would respectfully disagree and argue the crisis is still very much in place.

This included interviewing producer Zachary Quinto about his decision to take his name off of one of the completed films, which I completed on the phone in my TA office in Vilas Hall. Surreal moment, shoutout to the Starz publicity team.

I suspect Nanjiani was selected because of his close friendship with Issa Rae and because he co-wrote the excellent Big Sick with his wife. Perhaps he was meant to help with the rewrite?

To me, giving a new director a trash heap of a script is the worse sin of the series.

Not everything can live up to past Project Greenlight classics like "The Battle of Shaker Heights"