Week-to-Week: The Competing Imperatives of the Taylor's Version Project

Reflections on the righteous morality, crass capitalism, and compromised creativity of the artist's rerecordings

Welcome to Week-to-Week, the (mostly) weekly newsletter of Episodic Medium where I analyze television and other media industries, which is a broad enough framing to justify this deep dive into Taylor Swift’s album cycles. For more probably less-Taylor Swift-focused newsletters and to learn about what shows we’re covering weekly, become a free subscriber.

When I was working on my academic research on Taylor Swift’s fight to articulate her authorship, one of the most useful artifacts was a Forbes editorial that took a swipe at the singer-songwriter for losing her voice on her 2014 album 1989. The argument was that because she was teaming with pop producers, a historically “genuine” artist now sounded “fake.”

It’s clickbait trash, for the most part, but it created a great launching pad for my analysis of her very clear efforts to predict and confront this criticism in the release of the album. And yet, though I don’t agree with the article, it’s nonetheless been in the back of my mind as I’ve spent the weekend listening to 1989 (Taylor’s Version) and observing the discourse around it.

For all that I’ve written about Taylor Swift in the past (including here at this newsletter), I’ve actually never reflected in detail about the ongoing Taylor’s Version project. I’ve talked about it with students, both in my own classes and in a recurring guest lecture I’ve done for a friend, but I think I’ve instinctively been holding off from saying something more definitive with the project still very much in progress. But now that we’re four albums in, with only two to go, this latest release feels like a productive moment to reflect on the four imperatives driving the project, and how for a variety of reasons 1989 represents the most significant test of the ability for the righteousness narrative to resonate amidst increased criticism of the motives behind re-recording her first six albums.

I don’t know if we really need to go over the moral imperative that lies at the heart of the Taylor’s Version project, but let’s do the Cliff Notes version anyway. As a teenager, Swift signed a (pretty standard) contract that gave her label Big Machine Records ownership of her recorded songs. Those songs became the label’s single biggest asset, and when owner Scott Borchetta prepared to sell the company at the peak of Swift’s success he refused Swift’s offer to buy her master recordings because, put simply, the company had no real value without them. This transformed from a business issue to a personal one when Big Machine was purchased by Scooter Braun, who Swift holds responsible for the bullying she experienced during her feud with Kanye West. This fueled the revenge-tinged project of rerecording all of her past albums so that those master recordings (which Braun subsequently sold off to another company) lose their value, and she has full control over the songs’ future (e.g. licensing to film and television).

This moral framing of the project is its dominant imperative because this is how Swift framed it from the beginning, and how she continues to frame it. But we can’t pretend there isn’t a financial imperative behind the Taylor’s Version project, insofar as it ensures that Swift will continue to profit from the future streaming of her catalog, which is significant when you’re the artist with the most single streams in a single day in Spotify’s history. And this is further reinforced by the choices Swift has made in the releases: in a supercharged version of her historical album release pattern, every Taylor’s Version comes with endless exclusive album variants to collect, along with other limited-edition merch drops in the buildup to the album’s release. Anyone on the Taylor Nation mailing list—a.k.a. everyone who tried to get Eras Tour tickets—has been inundated with emails about the capitalist excess of the Taylor’s Version project, and it has no doubt been a huge financial boon for Swift.

However, the less cynical read on these choices is the third imperative, which is about nostalgically celebrating these albums and the fans who made them so valuable in the first place. The fan imperative has long been Swift’s justification for the shrewd business of numerous exclusives: sure, you have to buy four copies of Lover to get all of the journal entries she included in the Deluxe Editions, but then you get to feel like a “true fan” by having collected them all. And while there’s really just no way to sell that as anything other than “money grabbing” (four was too many, Taylor), the Taylor’s Version project has an added dose of nostalgia, as fans are given another opportunity to express their affinity for a particular “era” of her career just as that framework becomes enshrined by the concurrent Eras Tour. All of the extra albums and the extra merch exist because there’s fans out there who have strong emotional attachment to what each album meant to them at the time, and exploring that in a new context extends the bond between artist and fan.

Of course, it also clearly enriches the former at the expense of the latter, which feels particularly egregious when Swift is in the middle of the highest-grossing tour of all time and is making headlines for achieving billionaire status. And that brings us to the fourth and final imperative of the Taylor’s Version project: creativity. Although the choice to strive for sonic verisimilitude has meant that it’s hard to suggest the re-recording process is akin to the writing of a traditional album, there’s still a creative imperative to a more mature Swift voicing the emotions of her past. And more importantly, the choice to include “From The Vault” songs—left on the cutting room floor the first time—on each album has allowed Swift to clearly extend beyond the moral imperative. The Vault songs articulate the financial value of the albums to fans who already own the original, while also framing them as “gifts” to the fans in ways that encourage the nostalgia framing.

These four imperatives—moral, financial, fan, creative—have been present in the Taylor’s Version project since the beginning, and the challenge from a branding perspective for Swift has always been ensuring the virtuous frames obscure the financial one. When the moral, creative, and fan imperatives are emphasized, Taylor’s Version becomes not just about Swift reclaiming ownership over her songs, but also delivering the definitive version of those records that adds new layers to the autobiography they represent for her fans.

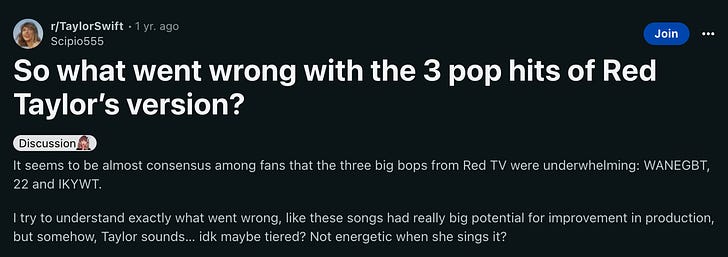

But this is a delicate balancing act, and the discourse around 1989 has taken a turn. For the first time, fans are speaking out against the “money grabbing” album rollout: the buzzards at Buzzfeed reported in August on fan response to Swift’s introduction of “48-hour exclusive” vinyl releases for the album, with one fan even framing it as Taylor’s “capitalist era.” On the one hand, this response speaks to a rejection of a very specific strategy, where new vinyl variants are surprise dropped without warning, and without letting fans see all planned variants to decide which one they prefer or letting them choose multiple variants and avoid paying multiple shipping fees. But there’s also the fact that Swift has now deployed strategies like this eight times in the last four years between new albums and re-recorded material, making it harder and harder to obscure the financial machinations operating in and around the artistry and creativity Swift would prefer to emphasize.

However, beyond the diminishing returns caused by Swift’s increasing returns, what’s becoming clear as we get deeper into the Taylor’s Version project is that the other imperatives are not always going to carry as much weight depending on the album in question. Fearless, the album that started the project, was always going to be able to leverage the moral and creative imperatives easily based on being first. However, the 13-year gap—and yes, this is probably part of why she released it first—also created a greater sense of creative reflection than in the case of more recent albums. This was the first time we were hearing her revisit songs from a more mature perspective, along with returning to a period where she was often adding an artificial twang to her voice to appease country radio as she sought crossover success with pop songs.

Red, meanwhile, represents the platonic ideal of the Taylor’s Version project (and involved the most significant press cycle, including the below appearance on The Tonight Show tied to her Saturday Night Live performance). The 10-minute “All Too Well” reclaims one of her most beloved album tracks as the crown jewel of her discography, while the other nine Vault tracks reveal new dimensions to the creative tensions of her album that most consciously straddles the worlds of pop and country (including songs from this era she gave to other artists like Sugarland and Little Big Town in the intervening period). Listening to Red (Taylor’s Version) feels like you’re finally hearing the full version of the story she was telling back in 2012 as a period of transition in her career is reconsidered from a period of relative stability to great effect.

But for the 2023 re-records, these narratives are starting to strain. Speak Now is an album that had a clear narrative at the time of its initial release: after facing accusations about her skill as a songwriter and her reliance on collaborations, Swift consciously released an album exclusively featuring songs she wrote by herself. And while the same is true for Speak Now (Taylor’s Version), it lacks a similar addition to the Taylor’s Version project—single “I Can See You” is notably a song that was likely too sexually-charged for her image at the time, but the other Vault tracks don’t really explore that tension in greater detail, creating a release that lacked the discursive depth of the previous re-records and the album’s original release. This is perhaps why Swift chose to move on so quickly, scheduling the next Taylor’s Version for less than four months later.

And this brings us to 1989 (Taylor’s Version). Despite not even being available on Spotify upon its release, the album is her most successful catalog album on the service, with three songs—”Blank Space,” “Style,” and “Shake It Off”—collecting more than one billion streams. It’s also the first album where there is minimal tension in her musical style: although there are a variety of different producers, she was consciously making her first pop record, including the beginnings of her collaboration with Jack Antonoff that would become one of the key building blocks for more recent eras. Put simply, the songs on the original 1989 more or less sound like the songs she’s released since, and have had the most longevity on streaming services.

And for these reasons, it’s much harder for one to argue there is anything beyond the moral and financial imperatives for re-recording 1989. There are still Vault tracks, but they don’t end up revealing new sonic dimensions from the era: all produced by Antonoff, they sound like songs that Swift has written and recorded in the intervening years, especially on her most recent Midnights. While the provocatively titled “Slut!” inspired hope for a revelatory new glimpse of her mindset at the time, we already have Miss Americana as an exploration of her struggles, and I don’t know if the song really adds up to much additional context. Taken as a whole, they’re the vault tracks that feel the least additive to the larger project, which isn’t surprising given how cohesive the record was to begin with. It’s also notable that after shooting music videos for both Red and Speak Now, no such videos have appeared for the Vault tracks on 1989.

In this and other areas, 1989 (Taylor’s Version) is creating more discourse around issues inherent to the Taylor’s Version project that have been present in past releases, but are becoming more apparent both in time and in context. The echoes of Midnights in the vault tracks continues an ongoing question of what creative work has been done to these songs once they’re been revisited. There was an initial version of this discourse when Taylor released the 10-Minute “All Too Well”—the “Fuck the Patriarchy” line in particular seems inherently anachronistic with the period, and made a fair case that while there were no doubt verses left on the cutting room floor at the time, collating them into a 10-minute version probably involved some fresh ideas. But with the production on these songs—especially “Suburban Legends”—sounding right off of Midnights, it’s harder to suggest that they were truly “in the vault” for the past decade. And while Taylor released some Voice Memos on Tumblr (to match those on the deluxe version of the original record), they don’t provide enough depth to really anchor these songs in that period in the way we saw on previous records.

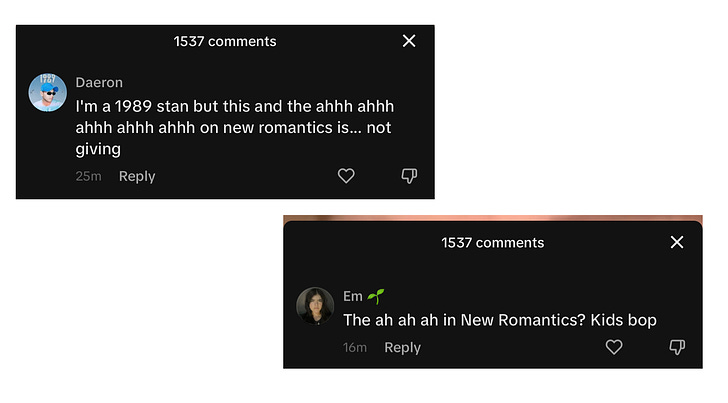

An additional challenge with 1989 (Taylor’s Version) is that we are reaching an era where the production on almost the entire album is becoming increasingly difficult to replicate. Throughout the project, there has been concern among fans regarding small differences between the original and Taylor’s Versions of certain songs, most pressingly with regards to the Max Martin and Shellback-produced songs on Red (in particular the “Oh” part of the chorus of “I Knew You Were Trouble”). And in the early reactions to 1989 (Taylor’s Version), fans reacted strongly to the new arrangements to songs like “Style” and “Bad Blood,” which…they just don’t sound exactly right. The songs are still good, and her vocals are maybe crisper and clearer, but there’s a sonic quality to the rest of the track—my brother refers to it as the “Max Martin Crunch”—that just isn’t quite there. As a “New Romantics” fan, this was another one of the songs that just lacked the same punch it used to have, and while I noticed the same issue on a few tracks on Red, the proliferation of the issue with 1989 made it resonate more.

On TikTok, commenters have battled back and forth on related videos about this issue, with some claiming they love the songs even more while others compare them unfavorably (and hesitantly) to Kidz Bop. Obviously, no one is arguing that any of the re-recorded songs are as bad as the inane lyrical changes or prepubescent harmonies of your average Kidz Bop Kids track, but there’s a similarity in the sonic experience of listening to something you’ve heard all over the radio or streaming constantly and knowing that something isn’t right. And while Shellback returned for the Red re-records, and for the off-cycle “Wildest Dreams” that was released alongside a TikTok trend, neither he nor Max Martin (nor protegé Elvira, who worked on “Message in a Bottle” on Red) are credited on 1989 (Taylor’s Version), implying they were either not invited or chose not to work to recreate their most successful collaborations with Swift for one reason or another.

The internet can—and will—dig into that fact for clues of some deeper feud, with TikTok comments often arguing that Swift swore off working with Martin based on his policy of taking credit on any song he works on (although she has never explicitly suggested this was an issue with Martin, who she thanks in the liner notes on this release). But the very fact hangs over this particular Taylor’s Version: if this was truly a creative project, wouldn’t the original collaborators all be involved? If she was truly committed to sonic verisimilitude for her fans, wouldn’t she do everything in her power to get Martin and Shellback onboard?

This isn’t to suggest there’s no value in revisiting 1989 in this way: the songs are still great! But re-recording them didn’t really reveal any new facets of them, and the Vault tracks are the least additive to date. And so while fans no doubt still support Swift on the moral underpinnings of the Taylor’s Version project, 1989 represents an album that strains the balance of the project’s various imperatives, no doubt leading to the increased frustration with the nickel-and-diming of the album rollout and the sonic imperfections in the album’s production. And while I could point to some of this as a byproduct of decisions made, I’d argue that the very nature of the album—its recency, its sonic echoes in the rest of her catalog—meant that this would always be a greater test of the project than any of the albums that preceded it.

That having been said, there’s reason to believe that the Taylor’s Version project will be able to sustain itself through two more album cycles. In the case of her debut record, which is highly suspected to be released last, it represents the single biggest gap between the artist she was and the artist she is now—by the time Taylor Swift (Taylor’s Version) comes out, it will have been nearly 20 years since she wrote and recorded those songs, and hearing them in a new context (and exploring what other ideas she was working with at the time) is going to carry thematic weight that other albums have lacked. As someone who only really started paying attention to Swift’s albums when she transitioned to pop, it will in some ways be the first time I’ve really paid attention to the album as a whole, which may be true for a significant amount of her fanbase in addition to peak nostalgia for her oldest fans.

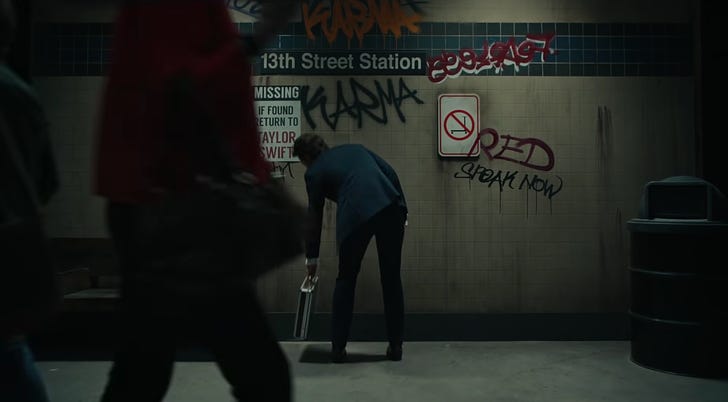

reputation, though, should have the same problems as 1989, given that it’s her most recent record being re-recorded and relies heavily on both her collaborations with Martin, Shellback, and Antonoff. However, provided that Swift follows through on what has long been rumored, reputation is actually the album that might have the largest creative imperative for a Taylor’s Version. Fan theories about a “missing album” called Karma that was conceived as a followup to 1989 have been circulating for years, and Swift herself acknowledged them in the music video for “The Man” and when she laughed hysterically revealing “Karma” as one of the song titles on Midnights last year. As someone who had released albums like clockwork every two years, Swift’s break from this pattern for reputation’s 2017 release had a logical explanation in the wake of the Kanye/Kim situation, but raised a related question: what happened to the songs (or at least song ideas) she was working on before all of that went down?

Even if the theories about Karma are overstating how close she was to releasing new music in the fall of 2016, the fact remains that her historical level of productivity suggests there was something happening that likely hit the cutting room floor, and there’s a greater chance of it representing a significant departure from the album we ended up getting. And so while it’s possible that reputation (Taylor’s Version) will just repeat the discursive challenges of 1989 (Taylor’s Version), there’s a much greater chance that we’ll get a deeper glimpse of both the artist and her art, which is closer in line to what these re-records can create in theory, beneath the crass commercialism that’s been wedded to the moral imperative.

But of course, the majority of fans are probably simply thrilled to have an excuse to revisit some of their favorite songs, and there’s no question that the Taylor’s Version project has worked alongside the Eras Tour to solidify Swift’s artistic legacy in ways that will define her career in the future. As such, no matter what unfolds with the final two releases, it’s clear that this will go down as a clear triumph for Swift as both an artist and a businesswoman, and most fans will probably accept these narratives without challenge. However, that doesn’t mean that there hasn’t been tension, and in the end 1989 (Taylor’s Version) will go down as the release that most embodies these competing imperatives when we look back at the project as she transitions to the next phase of her career.

Episodic Observations

Ultimately, “Say Don’t Go” is the best of vault tracks by a considerable margin for me, although I’m pretty annoyed that she didn’t include a Voice Memo on the song on Tumblr given that it’s a pretty surprising Diane Warren collaboration that we hadn’t heard about before. I would love to hear more about that decision, and how we can put it in conversation with her outreach to Ryan Tedder and Imogen Heap.

We’ll see what happens with reputation, but it just strains credulity to think that there wasn’t a single castoff from her sessions with Martin and Shellback on 1989?

I have more or less gotten used to the Red tracks that sounded a bit off, and so I expect the same will happen here—as it is, I found that I noticed the differences less when I had them on in the car, compared to playing them on my phone/computer.

I’ve never been a big merch person, and so I can’t say that I’ve found the merch drops to be particularly an issue, although the idea that she’s going to release a different cardigan for every subsequent re-release is definitely an example of taking advantage of fans’ collecting impulses.

Arguably, the most interesting “statement” Swift made about this era is actually in the prologue she wrote for the liner notes, wherein she directly addresses the longstanding rumors about romantic relationships with the women in her “squad” by noting how she believed no longer being seen with men would resist the media’s sexualized narratives. I suppose that it’s fitting that someone who didn’t understand that allyship exists would also be naive enough to believe that an artist so focused on love wouldn’t inspire discourse within her exclusively female friend group.

Back to TV for a second: caught the penultimate episode of Gen V on Friday, and…like, it’s not a poorly made show, but its actual plot is pretty thin on the ground, and it’s giving strong “this is just an extended pilot before the actual show starts” vibes that I’m not a huge fan of.

You know, Episodic Medium turned into a hard core Taylor Swift Substack so gradually I didn't even notice.

I started seeing jokes about “Scooter’s Version” (or should it now be “Hedge Fund’s Version”?) and for me 1989 is the breaking point. Taylor is now a billionaire (or close to it) so in terms of her interests, absolutely no one should feel guilty for preferring an original version of one of her songs. For me that’s “The Moment I Knew” from the Red cycle. I have always loved that song and I just can’t accept the new version. I actually am okay with 1989 (Taylor’s Version) and I also liked the new version of Speak Now. But it’s going to be very individual for how one chooses.

In general I do support this project in that I have seen so many artists screwed over by their record companies. A country artist I enjoy, Jamey Johnson, hasn’t put out new music (that he wrote) in years because of a dispute. Patty Griffin passed on the song Truth No. 2 to The Chicks because the record company refused to release her album for over a decade. That Taylor has screwed over her old record company makes me smile.

I am with you on the money grab. Have fans considered just not buying it? Or giving themselves a budget? Because there’s something to be said for choosing not to be fleeced. I say that as a super U2 fan who owns some rare LPs I found digging through Strawberry Records back in the day.