Week-to-Week: Red, White & Sacré Bleu

Amazon's queer romance adaptation was never going to be faithful, but did it have to be so feckless?

Welcome to Week-to-Week, the (mostly) weekly newsletter of Episodic Medium sent out to free subscribers. For more information on what shows we’re covering weekly, check out our About Page, and subscribe to receive future newsletters and updates.

I’m not going to pretend that I went into Amazon’s adaptation of Casey McQuiston’s Red, White & Royal Blue1 with an open mind.

When I first read the book in the summer of 2019, it was hard not to over-invest in Alex and Henry’s story: sure, I was neither the First Son of the United States nor the Prince of England, but I was a closeted bisexual who was grappling with the idea of that being part of my public identity as opposed to just a thing inside my head. And so the book—told from Alex’s perspective as the bisexual FSOTUS—became a pretty seminal text in my own understanding of self, and somewhere there’s a journal entry of my mid-pandemic reread that says as much.

But there was another dimension, which was that upon reading the book I became instantly invested in the idea of it being adapted, and horrified to discover that McQuiston had sold the movie rights—ahead of the book’s release—to a novel so clearly meant to be a limited series. This is a story begging to be explored in greater detail, with episodic structure used to flesh out the transition from enemies to lovers, and deepen the worldbuilding of both the backward aristocracy Henry suffers within and the cutthroat re-election campaign Alex’s mother faces as the first female U.S. president. The idea that someone could read this book and think “this should be condensed into a movie” was mind-boggling, and it fostered a pessimism that extended through the choice of director—a playwright with no film experience—and a casting announcement that implied the elimination of key characters like Alex’s sister, June.

So I can’t pretend that I didn’t pre-judge Red, White & Royal Blue, to the point where I planned the title of this newsletter before even watching it. However, I want you to understand that I am still shocked at how mad this adaptation made me, as I severely underestimated how much writer-director Matthew Lopez would be willing to destroy the fabric of the story I connected with in order to help Amazon sell books. Red, White & Royal Blue offers a perfectly charming story of two boys in love, but it strips away Alex’s inner struggle, the fact his sexuality would represent a crisis (either for himself or for his mother’s campaign), and the very notion that America as a country and the Republican Party specifically remain rooted in heteronormativity and homophobia.

And so even if my mind was closed to this film capturing the depth of the book’s characterization, I was not prepared for how quickly this film sells out the truths its story was built on.

In McQuiston’s book, Alex Claremont-Diaz believes himself to be straight right up until the point that Prince Henry of Wales kisses him outside the White House on New Year’s Eve, the culmination of their long-running feud turning into an increasingly intimate friendship over text in the preceding months. However, the “bi panic” that ensues reveals to the reader that this is not something that Alex hasn’t thought about—there was tween Alex’s obsession with a teen magazine photo spread of Henry for one, and then the drunken nights “playing around” with his best high school friend Liam for another. Rather, it’s something that he suppressed because it disrupted the vision for his life—politics, like his parents—and because he had learned through his parents’ divorce to bottle up anything he couldn’t easily resolve (and, when he got overwhelmed, to get drunk and end up at Liam’s). And as long as he also liked girls, his attraction to men was something he could repress comfortably within a culture of compulsory heterosexuality without feeling like it was a lie, necessarily.

Kissing Henry changes all of this, of course. And while he isn’t ashamed at the idea of being bisexual, he struggles with the implications it has for the life he had planned to lead. Even though he has a role model in Rafael Luna, a queer senator his father helped get elected, he still doesn’t want to create a bigger hurdle for himself than his Latino identity already creates. He’s open enough to talk about it with his close friend Nora—who is also the Vice-President’s granddaughter, and part of the White House Trio with him and his sister Joan—but he hesitates in telling his sister because he understands that she lives in the White House in part to be responsible for him, and doesn’t want to be a burden. He only tells his mother when her chief of staff finds Henry naked in his hotel room closet, which is scary less because he’s afraid she won’t be supportive and more that it’s hard to separate the Mom from the President running for re-election against a staunchly conservative Republican whose base would have a field day with this.

But in adapting McQuiston’s book into a two-hour romance, Lopez and co-writer Ted Malawer have effectively erased all of this (including the characters of Rafael and June in their entirety). When Henry kisses Alex, we don’t see Alex wrestling with what this means, or confronting his past repression—we just see the unanswered texts he’s sent to Henry, and then he’s chatting with Nora as though he’s just dealing with a run of the mill boy problem instead of confronting a huge moment of clarity about his past that makes the future incredibly unclear. That past is also devoid of much of the struggle from the book: while he discusses growing up in a mixed-race political family, the film inexplicably erases his parents’ divorce, which was a critical piece of the puzzle in terms of Alex’s entire approach to his life. They also insert an additional male love interest—political reporter Miguel, who he made out with naked in a hot tub during his mother’s campaign—into the timeline, meaning Henry isn’t Alex’s first adult sexual experience with a man, making this less of a startling moment of clarity and more Alex choosing to apply a label to something that he was seemingly pretty comfortable with.

The result is that as a movie Red, White & Royal Blue refuses to be a coming out narrative for its ostensible protagonist. The book tells a story about the specific struggle that bisexual people face in a heteronormative society, easily able to assimilate to expectation but knowing something is different, and not being able to confront that until faced with something as overwhelming as Alex’s connection with Henry. But in the world of the film, there is no inner turmoil, no struggle to reconcile past events—the facts are just the facts, and there’s no reason that this version of Alex wouldn’t be comfortable being out and proudly bisexual before the movie starts. He tells Henry in an email that he “came out” to his Mom, and there’s a quick line about how he feared that she would see him differently, but that fear is in no way reflected in the story being told, or in the direction of Taylor Zakhar Perez’s performance around it.

This is presented as a meaningful contrast from Henry, who is confined by the conservatism of the monarchy. This contrast does exist in the books, to be clear: the movie recreates a scene at a Texas lake house where Alex wistfully dreams of what their life could be like once the election is over, not realizing that Henry can’t let himself imagine that type of freedom given the confines of his “responsibility” to the Crown. However, in the book, Alex’s plans are in defiance of the high stakes of the campaign, a sign of how his love for Henry is igniting the fire of his stubbornness; in the movie, though, Henry explicitly argues that Alex has nothing to lose in going public in their relationship, and it would seem we’re meant to agree with him.

My read on this is that the film believes this is progressive—that it’s empowering to tell a story where Alex has no crisis of sexuality when Henry kisses him, because he’s a proper Gen Z celebrity who’s not confined to the binaries of sexuality that defined Lopez’s own generation. But the whole point of the book is that Alex and Henry both exist in contexts where they are confined to this even if their peers are not, and robbing Alex of his half of the story (or any character arc beyond the romance) guts their relationship of a crucial sense of discovery and reflection. The casualness with which he comes out publicly after their email correspondence is leaked—to the point we don’t even see his reaction to it—is a wonderful fantasy, but the deeper truth is that even as a part of Gen Z Alex exists in a real-enough world that his casualness in this moment elides real, substantive issues of homophobia and outright bigotry that exist in this country.

However, in the world of Lopez’s film, homophobia seemingly only exists within the conservative monarchy embodied by Henry’s grandfather, played by Stephen Fry. This was one of the casting choices that was confusing, given that in the books it’s Henry’s grandmother who is the ruling monarch. I found this choice perplexing, and the best explanation someone could offer was that they were concerned the actual British monarchy would take offense to a fictionalized version of Queen Elizabeth being depicted in such a negative light. And while they couldn’t have known the film would eventually be released when there is in fact a King of England with two male heirs, one of whom has been wrapped in scandal while the other serves dutifully, there did seem to be a conscious effort to sidestep real-world parallels where possible.

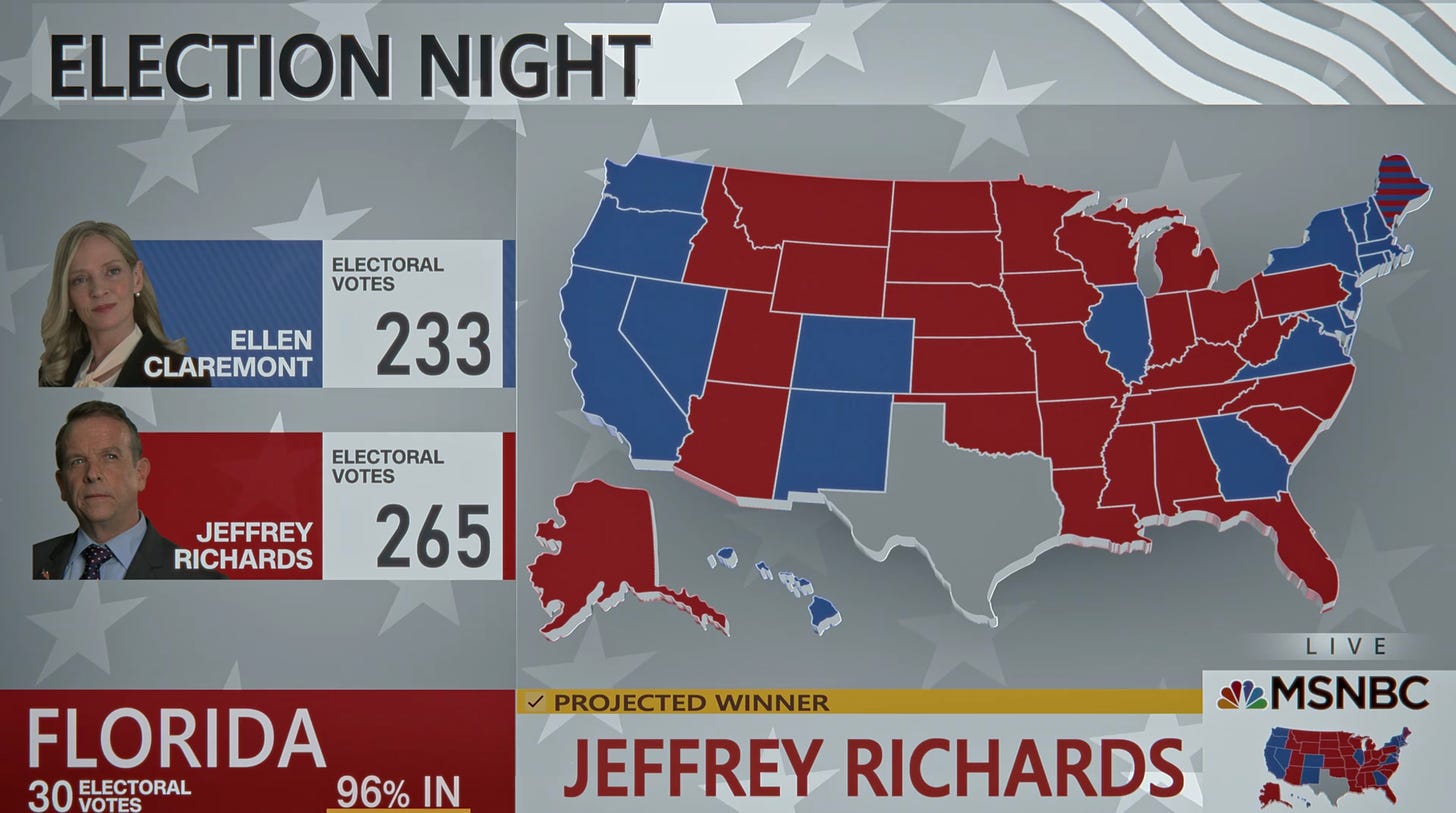

It thus seems fair to presume that the same was true for the engagement with American politics, which might explain the absolute travesty that is the film’s depiction of the ongoing Presidential election. In the book, which McQuiston developed as an alt-history response to Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016, Jeffrey Richards and the Republican Party are the real antagonists. While the oppression of the monarchy is an obstacle to be overcome, the Crown is ultimately forced to acknowledge their relationship, and is committed to a progressive path forward after Henry’s mother—also written out of the movie—reasserts herself against her mother after struggling following her husband’s death. But back in America, Alex and Henry’s emails aren’t just leaked online: Richards is revealed to have organized the hack of the private email server, a dirty political move his campaign pulls because they know that there are Americans for whom Alex’s sexuality would be a problem. And while the campaign’s win in Texas is viewed as a victory of progressivism and inclusion, and there’s a promise that Richards and his campaign might be held accountable for their actions, it still reflects a world where queer people are vilified by one of two political parties, a fact that won’t change overnight with this result.

Lopez’s film, however, has no interest in addressing this. Richards is reframed not as a socially conservative senator from Utah, but rather a jobs-obsessed governor of Michigan, with President Claremont’s concerns resting on the “midwest” and the “rust belt.” There’s no effort to address how queer issues would function within Richards’ platform, and the campaign seemingly has no involvement in the leak of the emails—instead, the film uses political reporter Miguel as its antagonist, because nothing says progressive like a jealous journalist ex who reports on emails—heck, perhaps even hacked and leaked them himself!—out of revenge for not sleeping with him. It sells out this random character, sure, but it also sells out the actual reality that queer people like Alex would face in America—there should have been a lot at stake for Alex when he stepped in front of a podium to address the country, but the film instead rushes through that scene and implies its only significance is whether Henry was watching in his Palace-enforced isolation.

It was obvious that condensing this story into a movie would make it impossible for the film to delve into the West Wing-style politicking the novel’s invested in, but trimming the story down was not contingent on making it seem like Henry’s sexuality was a crisis in his country but Alex’s wasn’t, a fiction of the highest order that does a disservice to the themes the novel is so invested in.

The result of all of this is a hollowed out shell of the story told in the novel, lacking the characterization and contextualization necessary to come close to reaching the same effect. Now, I don’t begrudge the joy the film could bring even in his form: it’s a perfectly winsome shell, and while I’m firmly against the casting of Taylor Zakhar Perez as Alex based on his height (Alex is canonically average height but overcompensates for it by being annoyingly charming), he had perfectly fine chemistry with Nicholas Galitzine, who benefits from Henry’s side of the story being more intact. And while every supporting character lacks the depth a limited series would have given them, even with some characters cut for space, Sarah Shahi gets a few nice notes as Zahra even if her secret relationship with Henry’s equerry Shaan is woefully underdeveloped (to the point where I figured they were cutting it, having done none of the scaffolding work).

But those were the types of issues I was prepared for. From the trailers and clips that have come across my social feeds, I knew that the vibes weren’t going to match the version of the story that was in my head. In a clip released on YouTube and other social channels, zany music and broad performances accompanied a scene that in the books is incredibly tense, with any and all humor being used as a coping mechanism in a deeply stressful situation. While the book is often very funny, I wouldn’t really call it a romantic comedy, but it was clear from the first images of the slapstick-style cake incident that starts the film that Lopez’s approach was going to be broader than the one I’d imagined.

But I hadn’t been so prepared for Alex’s story to be gutted entirely. It’s not just that the character seems a bit off from what I might have imagined—they simply made no effort to reflect his inner monologue, transforming him from someone struggling with his identity to someone whose only real problem beyond a cursory and fleeting commentary on being biracial is that he’s the President’s son and his crush is on a member of the royal family. I wish we lived in a world where Alex’s sexuality is irrelevant to his story, and I’m not accusing the film of straightwashing—Henry’s side of the story is very explicit that his sexuality is the point of contention, and the film throws out enough references to Grindr and Truvada that it’s clearly not ashamed that it’s about two queer men. But it wants to pretend that Alex’s sexuality would have no implications for his mother’s campaign, and doing so requires Alex to basically stumble into his bisexuality without meaningful struggle, lest the film have to stop to address the reality that being publicly queer as the first son of the United States is not far off from being publicly queer as a member of the royal family.

As noted, I never believed that a movie could capture the nuance of the book, and was prepared that it would struggle to reflect the story that I connected with so strongly. However, I didn’t realize that Lopez would make choices that were so uncomfortable with the actual crux of that story in the interest of depoliticizing and sanitizing the social context in which that story would operate. Perhaps Amazon didn’t think that the novel’s actual themes would sell enough books, or that the romance genre is incompatible with a story where the Republican Party is depicted as homophobic and led by a candidate who outs the President’s son and is revealed to be a serial abuser of young men and women within his campaign. But regardless of the reasoning, Red, White & Royal Blue arrives as a movie that wants to sell audiences the idea of the book it’s adapting without at all embracing the actual implications of that idea, and the result is a charming enough film that is nonetheless a bleak reflection on all parties involved.

Episodic Observations

Lopez is actively sticking to the WGA’s guidelines and only discussing his directing work in interviews, but I admittedly am not hopeful for satisfying answers once the AMPTP gives writers a fair deal.

An example of the film struggling to understand Alex’s character arc: whereas in the books he’s a Georgetown senior who abandons his plans to go right into politics to instead go to law school and help fight inequality in states like Texas, the film just makes him a law student, meaning there’s no real arc to his career path that could flesh things out. The same is true for Henry, whose life within the monarchy is entirely blank, compared to the books where he’s working on charity projects amidst a gap year after uni. The aging up of the characters is perhaps necessitated by casting older actors, but that’s just a reason to…not do that? Crazy thought, I know.

I knew something was wrong when “Bad Reputation” was used over the opening credits—both Alex and Henry extremely care about their reputations canonically, so that was the first hint that maybe Lopez didn’t actually understand the characters as we first meet them (even if, yes, they eventually learn not to care too much about them).

In the book, Percy—or Paz—is a flamboyant international bon vivant, and Bea is a recovering drug addict, and here they are…literally non-entities. The same is true for Nora, who is a wry and data-obsessed presence in the book, but who is just “a person Alex talks to a couple times” here.

Making Joy Reid and Rachel Maddow be a part of the show’s farcical presentation of news and politics was cruel.

The less said about Uma Thurman’s accent, the better. That said, she at least seemed to be committing to a performance: while eliminating the divorce does kind of rob Oscar Diaz of any particular reason to exist, Clifton Collins Jr. sleep walked through some atrocious dialogue.

Speaking of atrocious: the composting work on the fake White House and D.C. skyline was rough.

Although the film isn’t as horny as the book, the depiction of gay sex is still probably a “win” in terms of its explicitness. That said, I hate how they were forced to rush through their period of sexual discovery, which in the book have some really meaningful back and forth in terms of their dynamic across different encounters. I think the film’s best quality is that it still establishes physical and emotional intimacy between them, but it just isn’t the same when they’re not having sex at Wimbledon to spite the Crown, y’know?

Production design got points with a layup having Alex reading McQuiston’s follow-up novel One Last Stop, but they really couldn’t find a lake house with Spanish decor to better sell Alex’s heritage and how Texas embodies that? Sigh.

As noted, the film has no desire to create parity between Alex’s situation and Henry’s, but one way the book does this is by creating the “branding” of the White House Trio between Alex, Nora, and June, and presenting them as a tabloid subject and marketing strategy. That’s all lost here with June’s removal, and it makes it all feel very non-specific.

My award for the most needlessly damaging change goes to Henry getting Alex’s phone number from MI6 instead of giving it to Henry himself. Why would you remove his agency like that? Why would you take something where he acts on and affirms his shifting opinion of Henry and his embrace of his repressed feelings? For a playwright, Lopez’s dramaturgy is deeply suspect.

His attention to detail is also lacking: Richards’ dialogue during the scene of Alex brooding a bit as Henry ghosts him confirms it’s a debate, but the chyron when we cut to the TV suggests that Richards is “entering the race” in February of an election year. I know I’m a crackpot about verisimilitude, but have some standards, y’know?

I’ll be back next week with some thoughts on the third season of Reservation Dogs, and hopefully in a few weeks we’ll have a clear enough glimpse of the streamers’ intentions for Fall to discuss the schedule for the months ahead.

Amazon literally can’t decide its position on the Oxford comma, as they use it in the trailer’s title, but the formal title on its platform goes without, so I’ll swallow my objection.

There’s nothing wrong with Red, White and Royal Blue that couldn’t be fixed with a switch to a limited series format, a good script doctor, a recast featuring Michael Cimino as Alex and a younger actor as Henry, the buildout of side characters, the re-addition of ejected subplots, breaking up the parents again, fewer green screens, someone on staff who understands American politics and of course, more scenes of David.

I actually came off watching this last night excited, perhaps just from exhaustion. There were a lot of things I was ecstatic about. I actually liked TZP and Galitzine’s performances, for what the story allowed, and thought they had great chemistry (so no hate to them despite my recasting suggestion!). I never thought Amazon would air sex scenes that explicit or tender — kudos. Or the close-up shots of Henry’s butt in the saddle during the polo match. I though the way they depicted Alex and Henry communicating through texts and phone calls was as stroke of genius (though I’m sure someone smarter than me will point out that’s been done before) and wished I’d seen so much more of it. I laughed out loud at many lines, including “Little Lord Fuckleroy” and the exchange "They can't keep you locked away forever." "We REALLY need to get you a book on English history."

But all that said, in the cold light of day, I am forced to agree with pretty much everything you said. Much of it probably could have been fixed just by going to a miniseries format and upping the budget a little to match.

I want to point to Heartstopper as an example of a well-adapted romantic work. But that’s a graphic novel with simple plots, you argue. Fair. So I point you to Normal People, which was adapted from a novel and made me care about a het couple, and let me tell you that is no small feat.

It can be done. With thought and care, it can be done.

I mean, I’m gonna watch RWRB again. But I’ll be imagining how much more it could have been.

Hmmm. I agree 100% that RW&RB would have worked much better a miniseries. There's plenty of story in the book, and I did miss a lot of the same things that you did. But if you overlook that and focus on how well the adaptation works as a two hour movie, I'd say it's a qualified success. I admired the efficiency of the first half of the movie, even if I wish some of the early scenes between Alex and Henry had been given more time to breathe. It wasn't until the second hour when things started to come off the rails. Having no subplots meant that there was nothing else to do after breaking the boys up but to immediately get them back together. It was just kind of frenetic and silly.

I had two other big complaints: One, it just looked cheap. Maybe it's because I rewatch the West Wing endlessly, but those White House sets were dire. Two, like you I don't understand the choice to age up the characters*. This is not a teenage romance, but a lot of what makes it work is seeing Alex and Henry as very young adults just starting to figure out their place in the world. I thought Galitzine did a better job of selling Henry as someone who would be having these experiences than Perez did with Alex.

Given that they didn't have time for Liam as a character, I actually liked the way Alex copped pretty easily to having those experiences in high school and to the fling with the reporter. Something may have been lost by not letting us see Alex struggle with his identity more, but I don't think it's nothing that they make it explicit that Alex is into guys in general; it's not just a romcom kosher thing for princes. And I think the frankness with which the movie depicts intimacy between two men (and the discussions before and after) is a bigger win than you are giving it credit for.

When it comes to the politics I don't know. The Luna character was appealing in the book but I never really bought the role he played in the presidential campaign. And making Richards a predator and hypocrite, while far from unprecedented, felt kind of pat. I'm also just not sure I believe that a real-life Alex coming out would necessarily be a big deal politically. The Democratic party is a big tent and contains its share of homophobes, but only a subset of that subset care enough about that issue to influence their vote. I don't know the numbers (I bet Nora does!), but I suspect that in world in which Uma Thurman is President her bi son could come out without worrying too much about the electoral math.

* Seriously, they couldn't find any 22 year old actors? Are they all too busy playing 15 year olds?