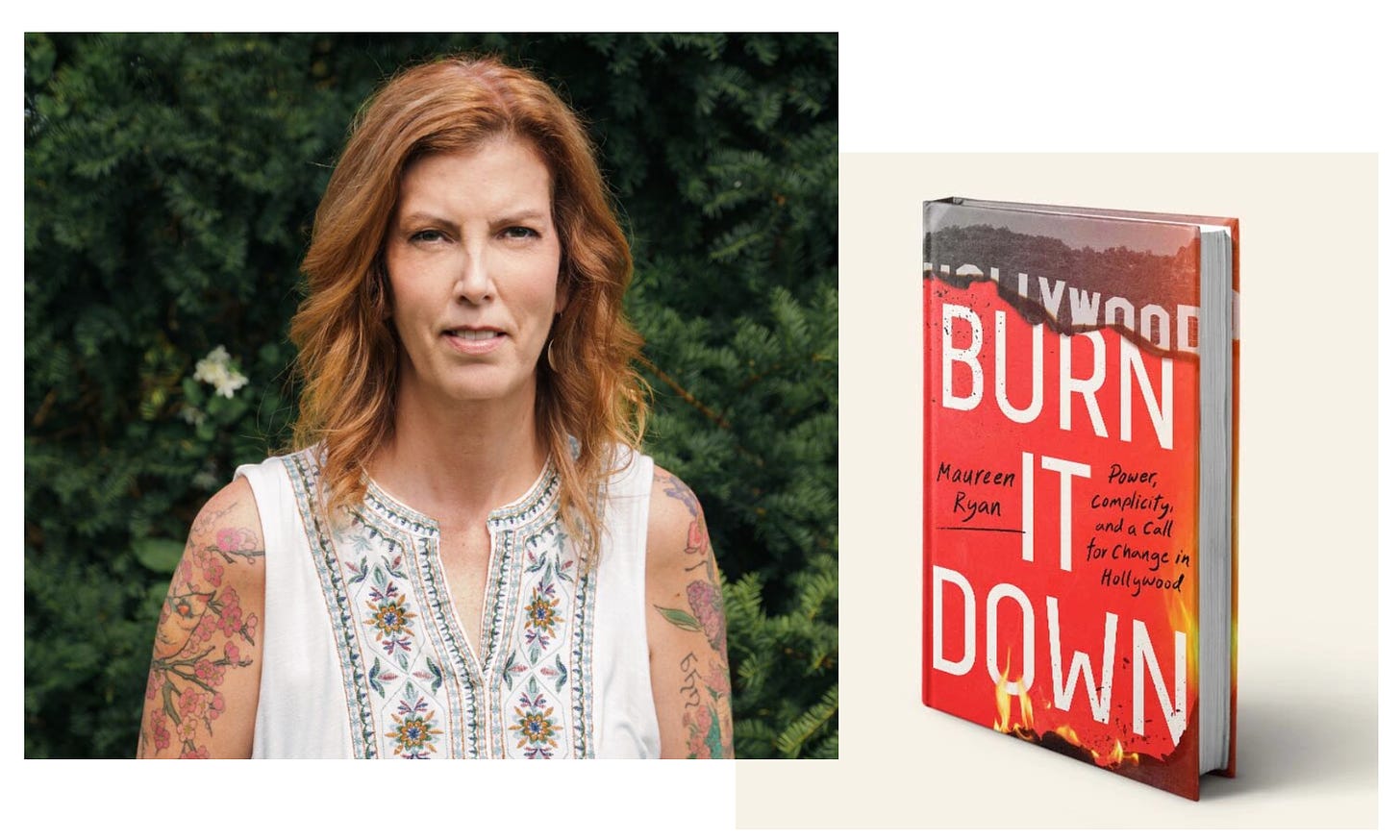

Week-to-Week: Maureen Ryan on the process of—and reaction to—her call to Burn It Down

A conversation about the broken systems of Hollywood and how we talk about them, then and now

As someone who has had the honor of calling Maureen Ryan a friend and colleague for over a decade, I’ve had a front row seat for the development of her new book, Burn it Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood, which is now available from Mariner Press wherever you buy books (and which I’m hoping many of you are already reading).

While I first got to know Mo primarily as a television critic within the golden era of writing weekly reviews like the ones we publish here at Episodic Medium, over the past decade I’ve seen her shift focus to investigative reporting aimed at producing a culture of accountability surrounding issues of race, gender, and sexuality as they manifest within both the culture of Hollywood and the shows/movies they make. In 2015, her reporting on a lack of diversity in TV directing led FX’s John Landgraf to make global changes to their reporting strategies, and in the wake of the #MeToo movement Ryan was a dogged follower of stories surrounding executives like Les Moonves and showrunners like Peter Lenkov and Andrew Kreisberg.

What always struck me about these reports was that it was never just writing an article. Beyond the complexity of reporting out a story with multiple sources in marginalized positions commenting on those with immense power in the industry, the response from networks often failed to address the root of the problem. Mo first reported on NCIS: New Orleans showrunner Brad Kern in December 2017, but was forced to return to the story in June 2018 when Kern’s behavior continued as a consultant, and was only able to report on his firing in October 2018 after a third investigation. During this period, Mo kept Twitter threads of each of these cases, updating them as more details emerged, reminding us that she wasn’t reporting on isolated incidents. This was a pattern of behavior, and the accountability she was seeking was less from these individuals and more from the industry that continued to hire and protect them. And so when Mo announced she was writing this book, I knew that she would be harnessing not just the incredible reporting she had done during this period, but also her work reinforcing the larger narrative that happened through her Twitter threads, and which kept us from ever thinking that a single article would solve these problems.

I had the privilege of reading Burn It Down ahead of its release, and it is everything I imagined it would be. It is meticulously reported and detailed in its articulation of the cultures of abuse and mistreatment at the core of the systems of Hollywood, but it also makes a conscious effort to imagine a better system, taking a big picture view of the industry and those within it. Its case studies are thorough, and if you’re someone who watched Sleepy Hollow or enjoys Saturday Night Live, it’s easy to lose yourself in the mental process of reconciling what you recall from those experiences with what was really going on behind-the-scenes. At the same time, though, Mo’s skill is in constantly pulling us out of the rabbit hole to remind us that while each case study has its own distinct forms of toxicity, there’s something larger happening that needs to be addressed, and which can be addressed if enough people agree to burn it all down and start over in a different image.

While I could have talked with Mo about the book and the stories within for hours, in chatting with her about the project I wanted to focus more on the process of writing it, and transitioning her ongoing beat reporting on this issue into a larger project. We exchanged these thoughts over a Google Doc over the past week, in the midst of the first excerpt from the book—an absolutely vital read on the racist and sexist workplace created and supported by Lost’s Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse—being published at Vanity Fair, which gave me the opportunity to get her first reflections on seeing her work in the book being received and interpreted by fans and those in the industry. I also had the opportunity to compare notes with Mo about how her book made me reflect on my own criticism of one of the shows she focuses on, and how her call for complicity ultimately includes those of us who wrote about shows like Lost in the way we did back then. I know our conversation is but one of the first of many that this book will be inspiring, and look forward to hearing in the comments how others are responding to this powerful and important work.

Myles McNutt: I don’t need to ask about whether or not writing Burn it Down was a personal experience for you, Mo, given how willingly you reflect on the process of immersing yourself in this morass of corruption and toxicity within the book itself. But I’m wondering whether you felt prepared for how personal it would become when you started—you’ve spoken in the past about your own direct experience with this harassment, but did the book end up being more personal than you imagined it when you began researching and writing in earnest?

Maureen Ryan: Oh, absolutely. I always wanted the book to feel as though I was grappling with the issues it contains, and not convey the idea that I had solved every issue and was talking down to people from the top of Perfection Mountain. Of course, there are some straightforward statements and solutions offered in the book. But I’ve made mistakes, and I’ve wrestled with a lot of issues and situations, and when it comes to the entertainment industry, I don’t necessarily feel that I’ve figured every single thing out.

Even so, it was hard to figure out how personal to make it. That was actually a huge reason to write a book—a book that ended up being longer than the one I promised my editor—because then I could include and fuse all these things: opinion, analysis, reportage, input from more than a hundred sources, personal reflection, and testimony.

A key breakthrough was realizing that when I dipped into analysis or opinion in the book, I could just be transparent about that. Putting in my two cents or sharing my experiences where appropriate actually helped contextualize some situations, I think. It helped to realize that it wasn’t shortchanging the reader to be open about the questions, ambiguous feelings, and the dilemmas I still had (or have). Quite the opposite, in fact—because I’d guess a lot of readers are still wrestling with a lot of ideas and questions surrounding the industry as well. I also enjoyed just saying some things I believe outright and very plainly. That was cathartic!

But of course, once you inject your own history and opinions into something, you make the entire enterprise more personal. I didn’t want to overdo or under-acknowledge that aspect of things, so I relied on the input of my great editor at Mariner, Rakia Clark, and from others who read early drafts of the book, and those folks and especially Rakia had really helpful input when I was veering too far in any direction. In fact, we took out one chapter that was quite different tonally—it was far more personal than the rest, and it just didn’t quite work in this book. (And don’t worry, we didn’t toss it – that piece about Charisma Carpenter appeared on the book’s publication date.)

Ultimately it was a constant balancing act, but one I grew more comfortable with over time. In a lot of places in Burn It Down, I include reporting, research, some analysis, a good deal of contextualization—and then there are times I add to that mix my own opinion and relevant experiences I’ve had. And if someone doesn’t gravitate toward those last two things, I think there are lots of other things to enjoy in this book’s buffet, so to speak.

MM: I ask the question because it had the effect you imagined on me, which is that you wrestling with these ideas pushed me to think about my own relationship to these issues. While I am in no means “part of” Hollywood, there’s a parasocial and at times social dimension to criticism (and to academia as well) in online spaces, and whether as a fan/critic/scholar/etc. we have been a part of the discourse around these topics as they’ve become part of our worlds.

While you’ve been the industry’s foremost critic on this beat for some time, did you find yourself—as I did—wishing for a time machine to go back and rethink how we talked about some of these situations in our reviews or social media feeds?

MR: Yes and no! It’s so complicated. I do think a lot of us were coming from a good and thoughtful place when we engaged with creators and showrunners and asked them about their work—and thus helped build up and burnish their reputations. The elevation of the word “showrunner”—and I can recall a time when it was not widely known or used—was not a bad development per se! But I think the hagiography that can sometimes affect the coverage of actors or other well-known creative people crept into what I was doing. I’ll only speak for myself here. Part of what I’m doing with the book is, I hope, atoning for or altering my approach to some situations and people and projects I didn’t question enough at the time.

I am, in some cases, re-contextualizing and adding more depth and detail to the histories of certain projects, because I think doing so matters; I strongly believe this additional information and context should be part of the narrative around those shows/films/workplaces, and of the histories of the people who worked in them. I’m very aware that we as critics, reporters, and editors help shape the perception of not just people or platforms, but of shows and movies that get talked about a lot. Of course, I’m not the only person doing this kind of re-contextualization and re-examination of the past (in some cases the very recent past – or even the present!). But in this book, in certain instances, part of what motivated me was thinking, “I’m not ashamed of what I wrote years ago—I only knew what I knew then. But what I know now also needs to be part of the narrative around this person or project. That should not be left out, ignored or conveniently swept under a rug.”

So I feel good about making that part of the work I’ve been doing for years, and those efforts are definitely in this book. But frankly I don’t know how to resolve the following dilemma: As I say in the book, I think it’s human nature to want to ascribe positive qualities to those who created work that affects us. It’s an understandable impulse. If we liked or loved or were simply interested in a screen story, it’s easy and tempting—and, again, human—to believe that those who made it share at least some of the positive qualities of the work. In a way, isn’t that a kind impulse? The idea that, from a place of engagement or emotional connection, we allow that transference and give creative people the benefit of the doubt? Never giving anyone the benefit of the doubt is a dark place to live (and I know that from experience, because some days, covering this industry turns me into a very cynical person, which is not a state I like to be in for very long—if nothing else, it’s a very boring mental state that makes your response to everything way too predictable).

All that said, yeah, I do wish I’d thought more about what “creative” or “passionate” or “driven” were really codewords for back in the day. I wish I’d thought more holistically about what it was like to work on these productions—for everyone, not just the most famous or rich or lauded people associated with that project (and even they may have had very rough rides). I’ve known for a long time that Hollywood workers who speak up about bad things can often face huge consequences for doing that. That’s part of what drove my turn toward doing more reporting—the knowledge that critics and reporters can say and write things that many people in the industry cannot, because they fear very possible and very severe retribution. I am actually proud of the fact that so many reporters, editors and critics who cover or critique the industry in any way are so honest in their work—despite the fact that, as we all know, rigor and honesty can affect access at times.

MM: Has your perspective on “access” shifted at all as you’ve engaged with these topics?

MR: I do not think “access” is a dirty word. I’ve worked for industry trades, and I’ve worked for all kinds of other publications, some of which had more access than others, all of which had differing agendas and various kinds of status or prestige or audiences. While I still wrestle with what we could have or maybe should have done more or less of in the past, I do believe this about the present: More people who cover the industry are, despite the perilous state of the media itself, using their platforms or their access to ask much tougher questions, and—when necessary—using their time and their work to poke holes in the myths that so many in the industry still cling to.

But all that said, the fact that media and journalism ecosystems are in such rickety states themselves means that there is a growing array of sites and writers providing worshipful coverage, and a lot more studios and networks are gatekeeping access in ever more creative and limiting ways—and I get why that’s happening on both sides, even if I don’t love it. Studios invest a lot in their “content” (ugh, that word), so they want it to be received well. And it’s so hard to get or keep a media-industry perch that getting “in trouble” with a big Hollywood entity’s PR apparatus can be a real problem. So, like I said, it’s complicated. But I am heartened by the fact that so many people who write about Hollywood and its output—and so many people who read that coverage—actually want these complicated and hard questions to be asked. And answered.

MM: As an academic, I’ve been more conditioned to consider these questions, and I’m equally heartened that more and more of our journalism colleagues are openly addressing them in their work. At the same time, though, I think part of what we’re reckoning with is how much we’ve internalized the norms of how Hollywood typically works in how we write about these situations. It’s not just what we didn’t know then: it’s what we knew, but understood and framed as a byproduct of Hollywood being Hollywood in regrettable but also intractable ways.

Your chapter on Sleepy Hollow and issues of race particularly struck a chord in this regard, bringing me back not only to the initial controversy around Nicole Beharie’s exit in 2016, but also four years later when I was named in a tweet as having defended the show’s treatment of her character as “progressive,” something I would never do.1 I searched frantically to try to find a tweet that would suggest this, and eventually caved and asked the person what it had been. What they pointed to was me, in the midst of a broader conversation in 2016 about shows navigating representing marginalized groups alongside complications within production, saying that at least Abbie was given a noble death with significant story implications compared to the rushed exits we saw for characters like Lexa on The 100.

Now, first of all, 2016 Myles should have known better than to argue Abbie’s death wasn’t so bad because it could have been more dismissive of the Black lead’s importance to the narrative. But these tweets were an offshoot of a piece I wrote about the perils of fan engagement on social media, wherein shows that actively courted marginalized fanbases were facing backlash for offloading those storylines amidst behind-the-scenes challenges. I always prefaced these comments with an emphasis that we can and should critique how shows failed to grasp the consequences of their actions, but it felt important to me at the time that we acknowledged the extenuating circumstances that created these representations lest we ascribe the creatives involved with a degree of racist/homophobic intent that we have no evidence to support. It’s a very academic take that pushes back against responses that foreground the individual actions/motivations of writers or producers in support of a more holistic view of the failures within the culture of production (which could, ultimately, uncover levels of personal responsibility).

But what your chapter on Sleepy Hollow really reinforced for me was how much this argument—much as I think it’s technically true—is used by the industry to justify inaction and avoid self-reflection when it comes to these issues. In 2016 I actually received emails from someone behind-the-scenes on Sleepy Hollow who thanked me for adding nuance to this discussion amidst frustration with how you and other journalists were responding to Abbie’s death. And at the time I admittedly saw this as a sign that I was helping us understand the industry by reinforcing how no creative decisions are as simple as they might seem. But in reading back over those emails, and in comparing it to what you uncovered in your reporting, I was really just giving them an out for their failure to account for how comprehensively the show’s leadership mishandled and exacerbated the tensions surrounding Beharie behind-the-scenes (regardless of the “truth” of what happened), and the inequities that occurred within.

And the truth is I did this because like you I’ve talked to many TV writers off the record, and they often detail examples of behind-the-scenes challenges that impacted what we saw on screen in ways they could never discuss, but which were far more complicated than the result. But whereas I naively believed foregrounding this reality in my criticism would help us interrogate the ideological corruption of the industry on a systemic level, our increasingly common social or parasocial links to creative workers means that “it’s the system that’s broken” manifests not as a call to further action, but as an effort to restrict and ultimately contain any such criticism.2 Even as we were preparing to have this conversation, you caught me interpreting your tremendous chapter on the toxic work culture at Lost in ways that were eager to relatively reduce (if not eliminate) the personal responsibility of Damon Lindelof, because that’s an easier path than confronting the contradictions between our perception of their work and the realities of how it was created.

Obviously, your book’s title—Burn It Down—emphasizes that there is no saving “the system” at the core of Hollywood, but my own response reminds us that we’re deeply attached to the fiction that a controlled burn is or was capable of addressing the problem. There’s undoubtedly a greater willingness to acknowledge systemic problems than there was when Lost debuted, but that chapter—an excerpt of which was published in Vanity Fair last week—is a litmus test for how willing we are to believe in the reformative capacity of those who have ultimately allowed that system to persist for the last twenty years. How optimistic were you that those of us who’ve been in the parasocial trenches during that period will not just be willing to ask these important questions, but also accept the harsh reality of the answers when presented with them? And how did that line up with what you’ve experienced since the excerpt went live?

MR: Whew, lots to think about here. I thought about all these questions so much while writing the book and even before.

So I’ll start with what’s topmost in my mind: The reactions to the Lost excerpt from my book, which Vanity Fair published last week, were generally different than I thought they might be. I am glad that that piece came out and opened the door to all those tough conversations. I am also aware the reporting made a lot of people sad and angry. Understandable, given that I felt an enormous gamut of emotions, many of them difficult, while writing and reporting it.

I worked so, so hard to get that chapter to a place that addressed complexity and nuance, but was also truthful and unflinching about what happened and how that could be and was a horrendous situation for many people. With input from my editor and from other trusted first readers, I did feel proud of that chapter (and the whole book), and I felt I’d landed that story in the right place. But, well, I’m a writer! I get nervous about reactions to what I write. What would the world think? Would they be angry at me for providing this much-needed addition to the coverage of Lost that I myself energetically participated in for many years? Would a subset of readers be looking for a way to absolve or explain away or ignore what occurred? Would there be a collective decision to memory-hole the worst of it, inside and outside the industry? But all in all, I found the response so, so heartening. (Especially heartening: The person who called the years-in-the-making piece a “trashy cash grab.” Twitter gonna Twitter!)

And here’s why. Just as many of us—myself included—ended up using part of our bandwidth over a period of years to help build a pedestal for a lot of well-known creators, showrunners, directors, and actors, in more recent years many of us—and even some of the people we write about—have used their voices and platforms to start questioning the automatic pedestal-ization of so many people. Not that we shouldn’t respond to good work, or recognize when individuals do good work, on and off screen. But we don’t have to build them up in the same way. Here’s something I think and have been saying for the last day or so—I think that Lost excerpt would have hit different five years ago. I don’t know that people would have taken its implications on board in the same way.

But since MeToo broke open and since there have been more public reckonings with abuse, racism, sexism, ableism, misconduct and unprofessional behavior of all kinds, a lot of us who write about culture—and those reading that writing—have had the scales fall from our eyes. At least some scales. We’re working on the de-scaling, anyway. The people who make the stuff we write about are just people, just as liable to be flawed as anyone else. And in an industry that valorized bullying and abuse as “creativity,” a lot of people saw terrible examples and decided to imitate them. We’re not as shocked and saddened by that information (maybe) as we might have been in very recent history.

And this is part of the point of my book: Those who had any amount of power, and chose to use that power to uphold the worst and most questionable or abusive norms of the industry – those who chose to imitate many of those who came before them and treat their colleagues like shit – we now are talking much more openly about the fact that that was a choice. As I say in a few places in Burn It Down, that was not inevitable, and I for one will no longer participate in the fiction that it was or is. Yes, leadership is hard and yes, not every bad act comes from a place of malice – so I write about that too! “What can we do to create better models” is a huge theme in the book. I am really glad that I talked to a lot of constructive people in the industry – in my book and within other stories about the industry – people who have clearly made a different choice, no matter what was accepted when they were coming up (and what is frequently allowed even now). I really, really want to shout from the rooftops that, for those with power, influence, access and wealth (or all those things), making the choice to continue the cycles of exploitation and mistreatment (financial, personal, professional, etc) – it is a decision, on the part of not just individuals but also big companies and industry studios. Individuals should answer for what they’ve done and change in positive ways, but we can also talk openly and frankly about this truth: It’s the studios and companies that bear the most responsibility for making terrible choice en masse, for decades. I’m frankly not that interested anymore in getting in the weeds about this or that individual – let’s talk about the whole array of people and institutions that allowed that person to keep making terrible and unprofessional choices. The industry culture as a whole is what powerful people and these companies decide to make it. Different choices can and are made every day, and we should also talk about that!

All that said, the question you point to in your own reflections—who’s to blame in certain complex and/or crappy situations, the institution or the individual—can be a hard one. In the longer book version of the Lost chapter, I go into the context around why Golden Age showrunners in particular were allowed to basically do whatever they wanted (and this still happens now in TV and film, alas!). One dry but very consequential legal decision directly informed the context around Lost and other shows of that era (and even now). The infamous Friends court case, which the California Supreme Court ruled on in 2006—at the height of TV’s brave new Golden Age—was twisted by the industry into something I don’t believe it was intended to be. The industry basically decided that this ruling about what can and can’t happen or be said in a writers’ room amounted to a greenlight for “anything goes” within Hollywood workplaces. And far too many people are still paying a horrible price for that series of institutional failings. Individuals were and are choosing to act in ways that are regrettable, and for a long time—and yes, sorry to be a broken record—those who wrote the paychecks at those workplaces usually turned a blind eye to all of it. All of it.

MM: Your book does a great job of exploring these unseen effects of broader institutional failure, but balancing that with more traditional criticism is definitely something that we weren’t doing when Lost was on the air, and was really something that was only first emerging around the time everything went down with Sleepy Hollow.

MR: I won’t get too far into the weeds on Sleepy Hollow — I really think that Burn It Down chapter has to be read in its entirety, because so much went awry at that show, on many, many different levels, that its impact as a piece of reportage is and should be cumulative. But I will say this about industry controversies and problematic workplaces and the like: When it comes to that stuff, I can wear my critic hat or I can wear my journalist hat.

If I put on my critic hat, I typically don’t care why some concern behind the scenes led to X outcome. (There are exceptions, but you get the idea). If a showrunner had to write out a character, an actor wanted to leave, or the show could not tell a certain story because of behind-the-scenes considerations, that’s not my problem. The people behind the show are literally paid the big bucks to figure out how to address that situation well. Or at least adequately.

How the creative team does the things they want to do or have to do (and the latter may be driven by non-story concerns)—as a critic, that’s what I’m assessing. Spoiler alert for The Americans, but that show killed off or wrote off people. Characters I as a viewer cared about. I could be wrong, but I think all those decisions were driven by story. But even if decisions like character deaths or relationships beginning or ending are driven by logistics or another agenda—on any show—it’s the creative team’s job to make it emotionally engaging and feel necessary or at least acceptable to me as a critic or viewer. The end.

Wearing my critic hat, all I can and should assess is what’s on the screen in front of me. Sure, other information may influence me at times, and does influence me at times (I’m human! I hear about or read about what may be going on behind the scenes!). But that’s really the thing I care about with that hat on.

Now, if I’m wearing my journalist hat, then I should do thorough digging if I’m going to write about something. Especially if a situation is indeed complicated and there are many parties with differing agendas and perspectives. It’s hard to meld all those things and sift through all those things! I do that a lot and it’s not easy! That said…what has really made me angry about some Hollywood situations is at times, on background or quite overtly, a storyline is put forward about what occurred at a certain show. And some of the time, people—maybe even a lot of people—didn’t do a lot of digging and questioning of who was putting forth that story and what agenda that narrative served. Sometimes, I gotta say, if you can’t do a story well, what you can do is avoid carrying water for someone who has an agenda that is perhaps not so wonderful.

But in order to preserve access or because, as you say, many in the media or Hollywood-coverage ecosystems (including me!) were kind of trained not to question certain dynamics or syndromes, truly unfortunate things happened and tremendously damaging narratives have been put forth; these were stories that damaged careers and lives, and may well be as fictional or heavily embroidered as any scripted story on a screen. And frankly, we still see this, right? When a publication3 is being used as a proxy for someone putting their “side” forward, all too often, it’s the side of those with the most power by far. Who is not being heard from? Who is discounted and discredited and doesn’t have the platform or the access that would ensure that their side also gets out there and is viewed as credible or necessary? The fact that the powerful still so often control many of the most important megaphones can and does have hugely negative ramifications for those who aren’t able to push back or get their stories out there. Social media can help now, at times, but as we’ve seen, the repercussions to a person’s life and career if they choose to speak truth to power can be catastrophic.

MM: Your book does a powerful job of modeling an alternative to this environment, but do you feel like we’re at a tipping point, based on what you’ve seen in doing press for the book? Can we upend the power dynamics of not just the industry itself, but how we talk about it?

MR: That remains to be seen. I think the WGA strike is about many things, obviously many financial and structural issues in the industry that ended up with most people in the post-streaming age working twice as hard to make half as much as they did a decade ago. But we’ve also seen a very blatant attempt to strip power from the people we thought were kind of Way Up There in the industry firmament: the showrunner, the creator, the key story architects, whatever you want to call the people whose work the media often writes about. I go into this a fair bit in my chapter about I.P.—part of the I.P. land rush is about making even showrunners work-for-hire gig workers who answer to enormous corporations who often give them little support or autonomy and treat them as disposable. Yes, we all maybe burnished some individual creators too much. We’re working on that! But I don’t think the answer is “treat creative people like Uber drivers who can barely pay their bills.” Something I think about a lot lately is this: Shawn Ryan (a hardworking advocate for positive industry change for a long time, by the way, and no, we are not related) was a basically unknown working writer when he walked into FX and pitched a show called The Shield—and they made it and it ran for seven seasons. I feel like so many parts of that simply would not happen today, and that’s a huge bummer.

But, in the bigger picture, what we can all do if possible—and what I’m doing more of—is talking to crews, midlevel executives, working writers, people not at the top of the org charts or call sheets (though sometimes those folks take big risks to help the industry move forward, it must be said). The more we do that, the more we can link the struggles of those in the industry—and yes, at times this even includes the “suits,” many of whom are as dismayed by a lot of the things we’ve talked about as we are—to a broader reckoning on whose work is valued, who gets treated decently as people or as workers, who gets to be able to pay their bills without being stressed out most of the time.

Someone working on an Amazon show and someone working at an Amazon warehouse: their situations are not all that far apart. And a low or even mid-level person working on a streaming show may have a more precarious and even dangerous job, and less sustainable career path overall, frankly. If we can strip away some of the perception of glamor about Hollywood and recognize that it’s not a dream factory, I think that might be something. The dreams should exist! I love imagination and storytelling and dreaming! But for the screen. The reality is much harder and more brutal than it needs to be. Is coverage of Hollywood coming from these kinds of mindsets enough to counterbalance the power of the executives at the top of these companies and the companies themselves? I don’t know. What I do know is if you had given 2013 Mo a list of names ejected from the industry by collective action by industry people and the reporters who cover them, I would have laughed and thought it was impossible. But it was possible. It happened.

We can all do one other thing I have been trying to do more of: I’m trying to eliminate the passive voice from places where it doesn’t belong. I’ll repeat something I wrote in the Lost chapter: In Hollywood in particular, “phrases like ‘I didn’t know,’ ‘there was so much going on,’ and ‘mistakes were made’ are common ways to frame terrible patterns of behavior—many of which are the result of terrible decisions, not the work of the disembodied hand of fate.” If bad things happen, and bad patterns keep occurring and grinding people down, I mean, a magic wizard didn’t do that. Those things happen because, as a group, many people thought/think those things were/are OK. When sometimes they really are not. And we need to talk about it. So far the reception to my book has been so energizing in part because I have seen a huge array of evidence that people are ready for those conversations. In the audience, in the media trenches, in the industry, a number of people are receptive to not just conversation but real change when it comes to all the things we’ve talked about. I am gladder than I can say that people are not turning away from these issues. That’s really wonderful.

Yes, I have a Tweetdeck search for when people use my name without tagging me. I do not recommend it, but know no other way to live.

Case in point: I remember an instance where a grad school colleague was presenting research on queer representation, and gave the example of Gossip Girl’s erasure of Serena’s brother Erik following his coming out as a sign of queer characters being marginalized. I immediately raised my hand in the Q&A to offer an explanation: it was widely reported Connor Paolo refused an offer to be a series regular, meaning the show didn’t have any guarantees that stories they built around the character would be able to function long-term. But the colleague was essentially like “So what?” And while I still contend that this additional context is valuable for distinguishing within patterns of marginalization, I also now see how my attempt at nuance functioned as a defense for that status quo in ways I hadn’t intended.

[Cough] Deadline. [/Cough]

Myles, one of your questions is NINE HUNDRED WORDS long.

Respect.

Mo is one of the first people I followed on Twitter way back in 2007. I loved her work as a critic especially championing cult genre shows like Killjoys and Wynonna Earp.

It is absolutely depressing that she has dedicated the last few years to reporting the toxicity of Hollywood, I wish she didn't have to but someone does and I am grateful for her hard work.