Week-to-Week: Better Call Saul, and an excerpt from why I fell behind on Better Call Saul

Episodic Medium welcomes Donna Bowman's coverage of the AMC series' final season, plus a relevant segment from my book, Television's Spatial Capital

This coming Monday, April 18, AMC debuts the first half of the sixth and final season of Better Call Saul, the critically-acclaimed spinoff to Breaking Bad which debuted in 2015.1 And when I told a fellow critic I was planning on launching this Substack and asked them what shows they thought everyone would be talking about this year, I wasn’t shocked when Better Call Saul was on that list.

There was one problem, though: I am behind on Better Call Saul. Okay, that’s an understatement: after watching the first season of the show, I missed the start of the second season, and outside of an episode I saw at the show’s 2016 PaleyFest panel I’ve entirely missed out on a series I know is extremely good, and which I’m sure I would enjoy immensely. I’ll get into why this happened in a moment, but the simple fact meant that I had no plans to try to cover the show, despite knowing even before AMC confirmed that Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul would be appearing in some capacity it was going to be a major topic of conversation throughout the year.

However, when I launched Episodic Medium, I got an email from someone who was in a very similar situation to me: Donna Bowman, who also isn’t a full-time freelancer, and in also stepping away from The A.V. Club was leaving her end-to-end coverage of both Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul unfinished. And facing the same dearth of freelance options that prompted me to start this project, especially in terms of sites without someone already covering long-running series, Donna wondered if Episodic Medium could provide a home for the final chapter of her 14-year (!) run writing about this universe.

And while I’m not yet satisfied with how much I’m able to compensate her for it given current revenue levels, it’s an honor to say that starting on Monday Donna’s reviews of Better Call Saul’s sixth and final season will be arriving in your inboxes as part of a subscription to Episodic Medium. I’m excited to avoid reading your comments in the naive hope that I’ll catch up on the entire series by the time the second half of the season starts in July.

One of the key reasons I fell behind on the show, though, is also something that I’m celebrating this week: tomorrow, April 12, my department is hosting a belated book launch event for Television’s Spatial Capital: Location, Relocation, Dislocation, which came out at the beginning of the year. And realistically, it’s no coincidence that I fell behind on a show that debuted right before I started a tenure-track job where the pressures of producing and publishing research determine your entire future. If anyone asks why I stopped watching—or never started watching—a given show during this period, I’m just going to send them an Amazon link to the book.

If you want to hear me talk more about the book’s genesis and some of the contents within, you can join the event—which runs from 5:45-7:15 eastern time tomorrow—via Zoom, and you’ll also get to hear about my colleague Allison Page’s excellent book Media and the Affective Life of Slavery. But in light of the coming return of Better Call Saul, I thought it was fitting that I take this week’s newsletter to share with you an excerpt from my fourth chapter, Discursive Hierarchies of Spatial Capital: “Like A Character In The Show,” which just happens to focus in part on Albuquerque’s “role” in Breaking Bad (and, by extension, its prequel).

And if you find this interesting and want to learn more, feel free to purchase the comparatively affordable e-book, or request your library of choice order a hardcover from Routledge, who currently have the book for 20% off.

Albuquerque’s Starring Turn: Place as Character in Breaking Bad

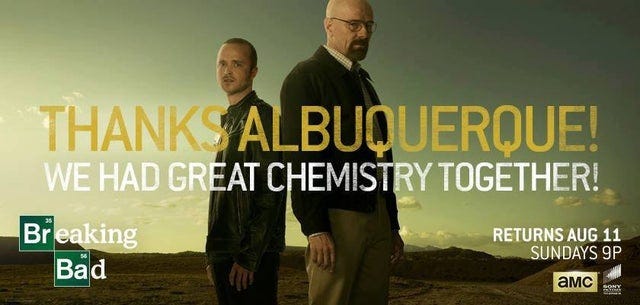

When AMC drama series Breaking Bad began the final episodes of its five-season run in the summer of 2013, the channel and the series’ producer Sony Pictures Television purchased several billboards commemorating the occasion. However, these billboards did not go up in Los Angeles or New York City to promote the series to the largest possible audience: they went up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where the series was set and shot. Featuring an image of series stars Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul, who played meth producers Walter White and Jesse Pinkman respectively, information about the series’ return date and timeslot were placed in small font in the bottom right corner of the image. In the middle of the image, meanwhile, was a direct message to the city itself: “Thanks Albuquerque! We had great chemistry together!”

These localized billboards reflect a mutually beneficial relationship between Breaking Bad and Albuquerque over the course of its production. As referenced in this book’s opening chapter, Albuquerque has emerged as a location for television production in part based on the visibility and production infrastructure created by Breaking Bad, to the extent that New Mexico’s 2013 legislation establishing increased production incentives was known as the “Breaking Bad Bill” (Couch 2013). The series—which tracked Walter White’s journey from cancer-stricken school teacher to drug kingpin—brought legitimacy to New Mexico as a filming location, its status as an Emmy-winning and critically acclaimed series building significant cultural capital for the state and the city of Albuquerque. In fact, it is one of only a small number of series filmed outside of Los Angeles or New York to win the Emmy Award for Outstanding Drama Series, and was the first since PBS’ Upstairs, Downstairs (1971-1975) to do so more than once.2

These billboards were far from the only location where the connection between the series and its setting was remarked upon. Writing for The New Yorker, Rachel Syme (2013) characterizes Breaking Bad as “a show organically tied to its shooting location,” arguing as a native New Mexican that it represents

the first story to truly commit the full spectrum of New Mexico to film: the grandiose visuals, the soaring altitudes, the banal office complexes, the Kokopellis and Kachina dolls, the seamy warehouses, the marshmallow clouds. The show seems to root itself deeper in the landscape with every new montage. It has become our newest monument.

Interviewing locals who have profited from the tourism of the series and reflecting on New Mexico’s aspirations to function as a media capital, Syme confronts the series’ “seediness and monstrosity” given its subject matter, arguing that “New Mexicans are proud of anything that draws us out of neglect, out of never really fitting in. We are just happy to be considered, even if it is for our underbelly.”

Syme’s is not the only piece of mainstream journalism about Breaking Bad that narrows in on its setting as a point of distinction: in other press, Albuquerque gains the status of a “character” in the series, as ascribed by those involved with the production and those analyzing its local impact. In a travel article focused on the series’ setting in The New York Times (Brennan 2013), series creator Vince Gilligan describes Albuquerque as “a character in the series,” a distinction that is further reinforced by Cranston in an interview with Albuquerque alt-weekly Alibi. He suggests Albuquerque has “become an important character to our show. The topography. Really the blue skies, and the billowy clouds, and the red mountains, and the Sandias, the valleys, the vastness of the desert, the culture of the people” (Adams 2011). The “characterization” of Albuquerque also emerges in a Forbes interview with series cinematographer Michael Slovis (St. John 2013), whose evocative images of that topography have become iconic of the series. The Santa Fe Reporter, writing about the series’ finale, makes the distinction as explicit as possible: “While many TV shows use a city as a setting, none have used it like a character like Breaking Bad did” (Reichbach 2013).

Breaking Bad embodies the qualities common to series in which place is framed as a character: the series is very notably shot on location in Albuquerque, continually sets scenes within the landscape, and has its sense of place reinforced through paratexts like the “Ozymandias” video released during its final season, in which Bryan Cranston’s reading of the Percy Bysshe Shelley poem is combined with a collection of distinctive time-lapse establishing images used throughout the series. The series’ surge in mainstream attention and ratings in its final season also amplified the visibility of media tourism to Albuquerque, where the intense online appetite for coverage of the series resulted in numerous unofficial paratexts where websites such as The A.V. Club visited locations like Walter White’s house and the car wash where he laundered his drug money (Adams 2013). The show has subsequently been held up alongside shows like The Wire as an exemplar of “place as character,” effectively putting Albuquerque on the map in the space of television culture and even creating a “recurring character” that remained central to discourse surrounding spin-off prequel Better Call Saul (2015-present).

However, although creator Vince Gilligan and cinematographer Michael Slovis have both been positioned as the creators of Breaking Bad’s Albuquerque, it—like True Detective’s Louisiana—was the result of financial considerations. Gilligan originally set his story of a teacher-turned-meth cook in Riverside, California, but before shooting the pilot producer Sony Pictures Television and network AMC made it clear that the economics would not work in southern California. In a roundtable interview with Charlie Rose in the buildup to the series finale in 2013, Gilligan spoke of his reaction to the mandated move to New Mexico to take advantage of its production incentives:

They said, ‘What’s the big deal, you put new license plates on that say California instead of New Mexico, it’ll be fine.’ And I’m glad they came to us with this idea, but I’m so glad I said ‘no, let’s make it Albuquerque.’ Because the sad truth of it is, unfortunately, you can’t swing a dead cat in this country without hitting a meth lab somewhere or other . . . It could be California, it could be—no one state has the lock on it, unfortunately.

These comments raise two crucial points within the conscious engagement with the discourse of “place as character.” First, similar to True Detective, Gilligan is acknowledging here that the basic concept of his series is untethered from the location in which it is set. Although the popular press articles cited above highlight how intricately connected Breaking Bad is to its geography, Gilligan is simultaneously claiming that it could have been set anywhere in the United States. Such a suggestion goes against the type of intricate, inherent place-based storytelling evident in shows like The Wire or Treme that originate with specific efforts to tell stories emerging out of Baltimore and New Orleans, respectively, and against the principles on which a strong connection between media and a particular city is typically constructed.

Secondly, Gilligan is legitimating his own labor by positioning himself as an agent of authenticity, contesting the studio and channel’s support of city-for-city doubling in favor of setting the series in Albuquerque, similar to Fukunaga’s emphasis on his and Pizzolatto’s respective labor in translating True Detective from Arkansas to Louisiana. Andrews and Roberts (2012) argue “landscape is understood as something that is ‘shaped’ and ‘produced,’ and by which is thus contingent to human or natural ‘processes or agents’” (1). In this case, Gilligan is placing himself as the figure more responsible for shaping the landscape, here constructing place as character through his conscious resistance to less authentic engagements with place. Breaking Bad may not have originally been set in Albuquerque, but the fact that it was his decision to do so allows him to retain authorship, while simultaneously reframing the series’ engagement with location in similar ways to how authors construct place as character within literature, despite the expansive amount of labor that goes into constructing those images relative to the descriptive language evident in literary works.

As evidenced by True Detective, the fact that Breaking Bad was not originally set in Albuquerque does not mean that the show cannot successfully claim place functions as a character within popular discourse. However, when the series as a whole is considered, the function of Albuquerque fails to live up to the claims that the show’s relationship with its setting transcends other televisual examples. There is no question that the setting is consistently used as a narrative backdrop to heighten thematic impact or draw out character distinctions as the narrative unfolds, and that the lack of representations of Albuquerque onscreen made this more notable than if the show had been set in Los Angeles or New York. However, the series rarely delves deeper into the spatial capital involved with the show’s setting in a way that elevates it to a narrative engine.

There is no question that there is conscious engagement with the landscape in Breaking Bad. In the series’ pilot, for example, the bank where Walt withdraws the money to pay for the RV is consciously isolated, surrounded by desert and mountains. Placing Walt’s scene with Jesse within the landscape as opposed to a crowded urban environment calls attention to the characters’ efforts to be as discrete as possible, while also previewing their journey into the desert to complete the cook in question. That iconic location, located in the Navajo reservation of To’hajiilee, becomes crucial again at the end of the series when Walt buries his drug money in the same location and ends up in the middle of a shootout trying to ensure its safety. In one of the series’ most powerful engagements with spatial capital, the opening scene of “Ozymandias” calls attention to this serialized use of location: beginning with a “flashback” to previously unseen moments from the events of the pilot, that scene ends with Walt in the foreground, and Jesse and the RV in the background, fading away. Then, following the series’ opening title sequence, we see the same location, this time with the action from the previous episode—two vehicles, Aryan gunmen, Walt, his DEA agent brother-in-law Hank, and Jesse—gradually fade in, the location the link between the past and present.

However, although To’hajiilee is central to the series’ narrative as a setting, its sense of spatial capital is defined purely through its aesthetic and symbolic value to the story. It is a landscape that is given meaning through the storylines that unfold within it, but the location itself holds no agency over that story—in this case specifically, the Navajo Nation plays no significant role in the series’ narrative, with the writers choosing not to engage with the cultural or political dimensions of those who own and govern the land in question. Although the episode is named after the reservation, and early speculation from Vulture’s Margaret Lyons (2013)—based on episodes of The X-Files (1993-2002), which Vince Gilligan wrote for, that took place on Navajo reservations—hoped that the episodes would explore the specifics of Navajo culture, Breaking Bad went no further in investing the series with the culture of the lands its characters occupied in these pivotal scenes. A Google search for “To’hajiilee,” as of January 2021, features primarily coverage of the episode by that name, with the minimalist Wikipedia page for the reservation itself pushed to second in the search results by the more-detailed Wikipedia entry for the episode of the series that bears its name.

Breaking Bad is undoubtedly leveraging spatial capital in these scenes, tied to its use of Albuquerque filming locations distinct from shows filmed in other parts of the country. Yet the series’ investment with place is limited by their selective engagement with spatial capital. Although the landscape is of significant value to the series, the place-making activities central to that community are less crucial. To’hajiilee’s name is actually a relatively recent development, which may in fact be part of the reason for its low Google ranking: in 2000, local high school law students petitioned to have the reservation returned to its traditional name, which means “the place where the water is drawn up,” from its then-present name “Canoncito”—Spanish for “little canyon”—which had been foisted on the tribe by President Truman (Nevada Government Session). This is critical to the culture of this location, yet this information is less valuable to the series given that none of the show’s main characters are of Navajo descent, and the root narrative of the series was—as noted above—understood to be unhinged to any one location within the United States. The series took full advantage of Albuquerque and the surrounding area to serve as an evocative and distinct backdrop for the series, but the resulting representations of place show limited engagement with the complexities of spatial capital, even if they are memorable for audiences and valuable for the future of local production in the region.

Albuquerque is not incidental to Breaking Bad: Gilligan could have chosen to use city-for-city doubling in order to retain his original Riverside setting for the series, and his choice to embrace the landscape is a clear effort to leverage spatial capital in a meaningful way. However, the discourse of place as character says less about the actual function of location within the narrative and more about its discursive value to Gilligan as a writer, to other members of the production, and to Sony and AMC as its producer and distributor respectively. The specificity of framing it as a character, though, anchors that spatial capital within the area of above-the-line labor, despite the fact that it is below-the-line workers like location professionals who are actually responsible for turning a landscape or cityscape into a significant part of a story. It is a discourse that, accurately or not, roots location in the very genesis of the story itself, meaning that any labor from the show’s location manager Christian Diaz De Bedoya and his team is framed as executing—rather than shaping—that vision to a greater degree than if the discourse was not present.

This is not to say that Gilligan and the executive producers of both Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul have elided Diaz De Bedoya’s contributions to the series. In a fan Q&A on AMC’s website (2011), Gilligan was asked how they find locations for the show. In response, he explains Diaz De Bedoya’s role and outlines how the work locations does ahead of each season is critical to their creative process:

At the beginning of the season, they also go out and photograph places that they think are visually interesting. Typically, we’ll have a meeting at the beginning in which they show us these photographs and discuss them. Very often we’ll get inspired by these possibilities location-wise and we will indeed write to certain places that they find for us.

In an interview with Better Call Saul co-creator Peter Gould in The Hollywood Reporter (O’Connell 2017), Gould identifies Diaz De Bedoya as the person on the show who has the most difficult job, noting that the members of the location team “have an almost impossible task: finding new, expressive locations in a city we've been shooting in for almost 10 years. He comes through for us every single day and does it with effortless good humor.” Given these statements, this is not a case of the producers of the series actively trying to supersede the location team’s role in the production.

However, because locations professionals are so far below-the-line, they are rarely allowed to articulate their own contributions to a given series in outlets of this nature and are rarely credited in reviews that hail the show’s relationship to Albuquerque. If Albuquerque is indeed a character in the show, it depends on the locations team finding the right locations, but their labor is largely elided because it does not fit comfortably into the cultural hierarchies of where creativity rests in the collaborative production of television, and which the discourse of place as character situates further within the authority of showrunners and producers. In the aforementioned 2019 Los Angeles Times story about place functioning as a character in television series, which valorizes filming on location, Diaz De Bedoya discusses Better Call Saul’s use of Albuquerque, but only below Gould’s larger statement about the production’s view of the city’s role in the story. When Entertainment Weekly did a large profile on the different locations used throughout the prequel series, they interviewed Gould and fellow executive producer Melissa Bernstein, but not Diaz De Bedoya, who is credited by Gould only for maintaining relationships with the distinct owners of two interconnected locations (Snierson 2020). Although AMC’s website did interview Diaz De Bedoya’s predecessor Scott Clark after Breaking Bad’s second season (2009), they never interviewed Diaz De Bedoya about his contributions to the series’ acclaimed final seasons, and no video content for YouTube channels or DVDs were produced with any members of the locations team as they were for figures like cinematographer Michael Slovis.

The only space where Diaz De Bedoya was able to speak at length about his role in either series is the aforementioned paratext produced by The A.V. Club, a Pop Pilgrims video where hosts Erik Adams and Emily St. James tour iconic locations from Breaking Bad with Diaz De Bedoya (see Figure 4.3). In the writeup accompanying the 2013 video, Adams notes the credit that Slovis and the show’s directors like Rian Johnson often receive for the series’ visual signature, but argues that “were it not for Diaz De Bedoya, his fellow location managers, and their intimate knowledge of ABQ, Slovis and Johnson would be shooting against a less idiosyncratic canvas.” It is one of the rare instances where Diaz De Bedoya gets to speak to his role in the series at length, and in the video, he gets to—for the first time—be the one to make the all-important claim that Albuquerque is, indeed “a character in the show” as the person most directly responsible for ensuring the show has access to the locations that make that possible.

But by reiterating this discourse, Diaz De Bedoya is further distancing himself from both series’ spatial capital, entrenching it within the creative class of workers that “place as character” ultimately benefits. Much as a certain class of show can more successfully assert place’s role as a character in the story, so too can a certain class of worker benefit from deploying this discourse, even in circumstances where the initial creative instincts of the series were not based on the location in question. When Josh Wigler (2015) previewed Better Call Saul ahead of its premiere, he wrote that “more than a year after Walter White’s final curtain call, we’re back in the Albuquerque of Vince Gilligan’s mind,” a rhetorical turn owed in part to how reiterating place as character orients spatial capital within the power of Gilligan and showrunners like him.

Yes, they’re only airing the first half so the show can straddle the Emmy eligibility period and rack up two years of nominations, all of which they are probably guaranteed to lose in an environment where Succession is sucking up all the oxygen.

In the years since I first wrote this section of the project in 2014, this balance has shifted: Succession is the only show to win Drama Series that WAS shot in New York or Los Angeles, with Game of Thrones, Handmaid’s Tale, and The Crown rounding out the lineup.

@Myles were you able to catch up on Better Call Saul before tonight's finale?

this was fascinating to read, thank you for sharing it :) I haven't seen any BB or BCS, but I have watched every episode of another show set and shot in Albuquerque, USA Network's In Plain Sight (which I do recommend for various reasons, including the fact that it features a rare "grumpy lady" protagonist). I would be very interested in reading an analysis of how place fits into that show.