Week-to-Week: In Defense of the "Dream" Interpretation of Ted Lasso's Finale

Yes, I know they're claiming they didn't intend it to be a dream, but hear me out

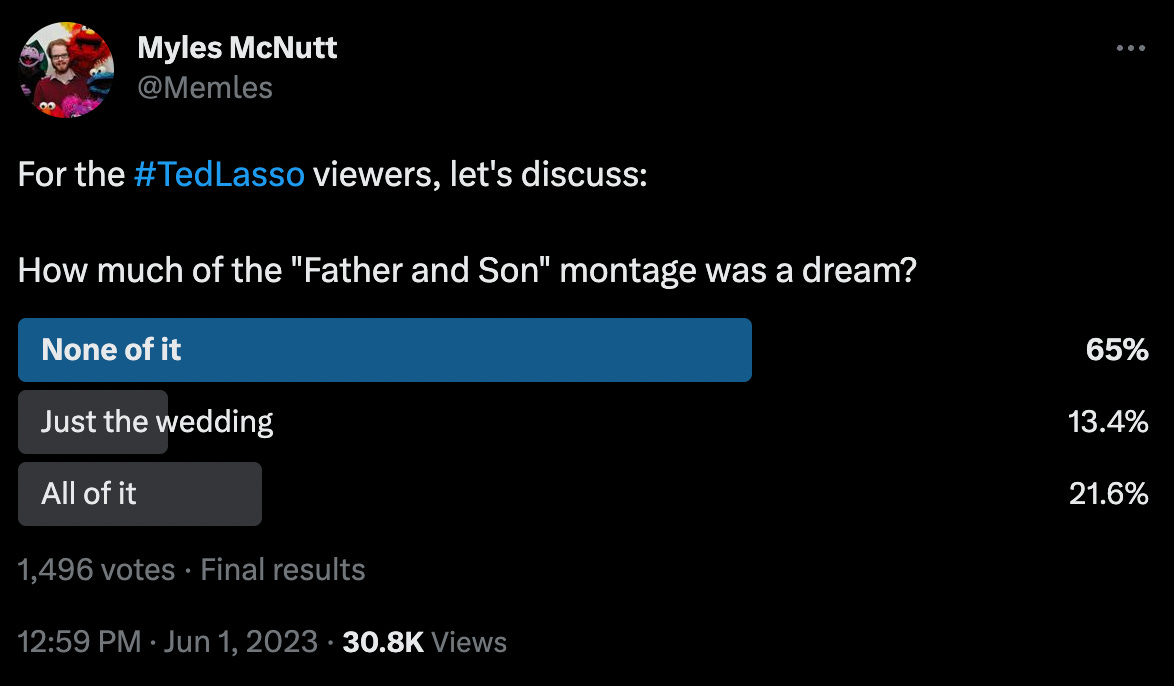

Yesterday, I posted a Twitter poll based on a simple question: how much of the final montage of Ted Lasso’s third season was a dream?

See, when I sat down to write my own review on Wednesday morning after having stayed up to watch the finale, I talked myself into not even posing this as a question: I was certain that based on what was presented in the text, it was a dream. But when subscribers started commenting, and as I saw the Twitter discourse evolve, it became incredibly clear that this was a minority position, and the results of the poll bore this out. The majority of viewers chose to interpret this sequence as reality, and co-creator Brendan Hunt was explicit in a Reddit AMA that it was not in his view intended to be interpreted as a dream.

What struck me about the response, though, was how there was a presumption that my choice to interpret it as a dream had an ulterior motive based on the content within the sequence. I want to be clear, then, that I truly don’t care if what we saw in the sequence was a dream or not—in fact, I was so relieved that Nate wasn’t the head coach that I was more than happy to see it as real until I rewatched it. I just feel there are some absolutely bizarre choices happening in and around the sequence if we were never meant to question whether or not it was really happening. And so I find myself defending this interpretation less because I need it to be true, and more because I feel like the internet is gaslighting me about whether or not there’s evidence in the text to support it.

Ignoring the content within the montage for a moment (I promise we’ll get to it), the strongest evidence supporting a dream interpretation is how the sequence begins and ends. It starts with Ted opening and then shaking the snowglobe that Keeley has regifted him after Barbara refused it earlier in the season. And while we don’t get a full zoom-and-fade before shifting to Trent finding the book manuscript, there’s no ignoring the Tommy Westphall of it all when it comes to snowglobes playing a role in pivotal finales. It creates a framework to view everything in the montage less as pure fantasy, and more as Ted’s wistful hopes for the friends he’s leaving behind, so as to make him feel better about the choice he’s making (which is further supported by all the Wizard of Oz motifs that have been sprinkled throughout the season).

This is, of course, reinforced by the final moments of the montage and our transition back to reality. Beard’s Stonehenge wedding is not just an intimate moment for Beard and Jane. It is a full-scale, visual effect-enabled reunion of the entire cast except for Ted, who despite being depicted as Beard’s best friend is absent at the wedding. Then, as we leave the scene of the wedding, we return to Ted asleep on the plane, the light in his eyes matching the golden hour hues from Stonehenge. He then wakes up holding a copy of Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind: What The New Science of Psychadelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, and we transition into the final scenes of Ted settling into his new (old) life with his son.

Now, in fighting against this interpretation, people have pointed out some perfectly logical arguments. How could Ted have dreamed the existence of Rebecca’s Mr. Amsterdam when he doesn’t know they reunited at Heathrow? What if Beard organized a last-minute wedding and Ted could have—as Hunt suggested on Reddit—been busy with Henry’s soccer game? Hunt made the argument in his AMA that

“the history of their relationship IMO is long periods of seeing each other and long periods not. We have entered one of the latter, but the former will come around again at some point.”

And while I would contend that the idea of a last-minute wedding that his best friend couldn’t attend but which could be attended by literally every other cast member strikes me as absurd, we don’t have enough details to definitively state it’s impossible. This could absolutely also be a real wedding that Ted didn’t attend.

But the choice to turn Beard’s wedding into a full-cast reunion aided by some dodgy CGI compositing work set against an almost uncanny virtual Stonehenge makes the whole thing seem like a fantasy, like Ted imagining all of the people who populated his life in London together in the most extra way possible. And while most of what we see in the montage preceding it is pretty boilerplate, Sam playing for the Nigerian team is another example of a development that requires leaps in logic that we want to believe but which would have to overcome Akufo’s influence and the criticism Sam would have faced for being politically outspoken. When you combine all of these components together, it is easier for me to interpret this as Ted’s dream for what he left behind than a logical series of events given the information available to us in the text.

If you were to adjust any one of these elements, though, that changes. People have brought up the ending to Six Feet Under, which similarly combined a desire to remain with a character’s perspective—in that case Claire—while also flashing ahead to show us the rest of their lives. But in that case the montage consistently cuts between Claire and the flash-forwards, and Claire is present in those flash-forwards, making us less likely to interpret they are simply taking place in her head. If this montage had been constructed so that we were regularly cutting back to Ted opening other gifts, or going through a photo album, then there would be a stronger case that we were seeing their real futures. But when you instead cut away from Ted entirely and only return as he’s literally waking up, it becomes harder for me to understand why you would make that choice if you didn’t intend the audience to wonder about the provenance of those scenes.

And honestly, wondering about them seems super productive and consistent with the goals of this finale for me. Thinking about it as a dream doesn’t invalidate anything we see, or even imply that it could not or should not happen. Rather, it embodies the finale’s awkward efforts to live in the liminality of a show that we know Apple wants to continue, but which remains in limbo thanks to the creative team’s unwillingness to commit to a future. Read as a dream, the montage gives the writers the ability to say that this was a series finale where everyone got their happy ending while also leaving room for them to return to the Richmond storylines from a new perspective if they so choose.

I absolutely take Hunt at his word that this was not intended to be interpreted as a dream when it was originally scripted, but I struggle to accept that no one involved in filming or editing this episode thought consciously about the possibility given the choices involved. But the truth about any form of media is that intent is not reality—meaning is shaped by interpretation, and Ted Lasso chose to tell so much of its final season off-screen that it’s created a logic vacuum that will naturally be filled when you line up semiotics like they did here. And so I defend the dream interpretation less because I need it to be right, and more because we’re now at a point where there is no right and wrong. There’s just your personal interpretation, and mine is one where everything between the snowglobe and Ted waking up is his brain convincing himself that everyone will be okay without him.

Episodic Observations

Something this discourse really underlined for me was how much the season took for granted the idea that Ted needed to leave to be with Henry. I have no doubt that he needs to be there full-time, but the idea that he would be severing his connection to the degree that he would be making a Mary Poppins exit doesn’t actually track. This is a world with a direct flight between Kansas City and London. Rebecca is filthy rich, and Ted would have been paid handsomely as a Premier League coach. And Beard was seemingly Ted’s only close friend, meaning he was returning home to what appeared to be no support system to speak of. The idea that he wouldn’t find the opportunity to fly to London for a weekend? It just doesn’t add up, dream or no dream.

Although Dani waking up in bed with two women was real, it happened after his dream about killing the dog back in the second season, and so that association was definitely still in my mind when that bit came up at the end of the wedding sequence.

The most interesting information in Hunt’s AMA wasn’t the comments about the dream of it all, but rather his confirmation that Apple TV+ pushed back the finale’s release by three hours literally because they hadn’t finished it yet, which really does explain the state of some of the visual effects.

With so many shows to be covered, I haven’t been watching a huge amount of TV that we’re not reviewing, but I did make time for Freevee’s Primo, which I might end up writing more about as I think about the idea of “value” and our streaming attention spans. But it’s definitely worth your time to check out while I wait to find the right moment to delve deeper into it, even if I couldn’t help but imagine how much more of it we’d get if it had been a traditional broadcast sitcom.

I did however get to Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse last night, which was really quite excellent even if it’s unavoidably hamstrung by being half a movie. It’s gorgeous and dynamic, and nicely balances the macro-meta dynamics of All The Easter Eggs Ever and the micro-meta dynamics of the world of the first film, both of which feel vital and generative. Excited to see how they bring things home next March.

I think they simply made the choice they did because they knew it would send Myles over the edge.

I was absolutely floored by the suggestion it *wasn’t* supposed to be a dream - or, at the least, ambiguous bet-hedging so they can erase it all as fantasy in case of a spin-off.

Similarly - I don’t really care either way, but my honest reaction to a close-up on someone waking up, is that the preceding sequence is in their dreams. That’s a pretty long-established cinematic language.