Week-to-Week: How SAG-AFTRA's call for solidarity became a morality test for fans and content creators

Doing your job or expressing your fandom isn't scabbing, and we're missing the point if we treat it like it is

When the WGA went on strike back in May, there was a general sentiment of solidarity within the corners of the internet where people discuss and engage with TV (including here at Episodic Medium). And while solidarity means different things to different individuals, there was largely no disruption in the day-to-day activities of this group of people: the strike was something that fans and critics talked about, and which shaped our discussion of film and TV in various forms, but we mostly kept on keeping on.

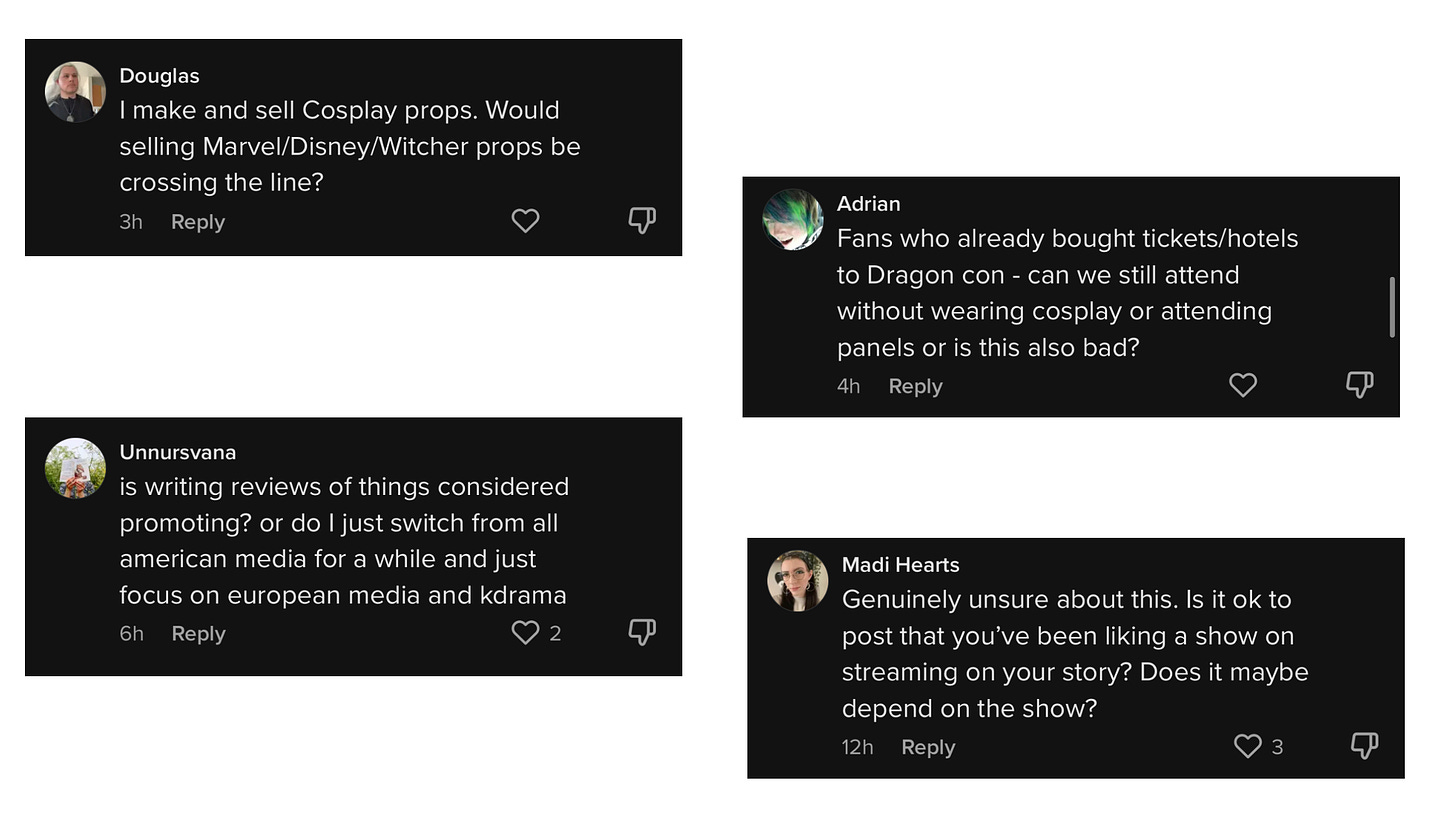

However, when SAG-AFTRA went on strike last week, there was a strikingly—pun intended—different reaction. Unlike with the WGA strike, there emerged an understanding of solidarity that involves ceasing any and all discussion of film and television, lest it be construed as promotion on behalf of the television industry. Initially this was primarily driven by content creators, but soon the conversation was extending to “reviewers,” critics, journalists, and even fan cosplayers. Screenshots of email responses from various SAG-affiliated individuals became gospel, and my TikTok FYP became filled with videos of creators navigating a moral minefield of decisions where no clear rules had been established.

SAG-AFTRA has since co-signed an effort by Variety to offer clarity on these issues, but the discourse ran wild before that happened, and my response can be divided into two categories. Firstly, as an academic, there’s a fascinating conversation happening here in terms of how different groups of individuals see themselves and others relative to the promotional engines of the film and television industries. The most militant interpretation of the SAG guidelines suggests it is unethical to engage in any activity that could be construed as promoting the companies that make up the AMPTP, whether that’s cosplaying as a character from a TV show or tweeting your reaction to a new movie. The argument goes that there’s no difference between a TikTok creator working directly for a studio in promoting an upcoming film and simply making a TikTok expressing their reaction to that movie, given that the end result—increased awareness for a struck studio’s film—is the same, making any engagement with upcoming film and television projects against the spirit of the strike.

It’s a really meaningful conversation to be having across all of these contexts. It’s especially vital in terms of thinking about content creators who work closely in tandem with studios, their parasocial relationship with their audience inextricably tied to their brand partnerships. However, it’s also a meaningful question to ask how publications like Deadline exist in symbiosis with the entertainment industry they cover, particularly if we were to isolate contexts like awards campaigning, and the discussion about cosplayers points to ongoing academic discussions of “fan labor” and the industry’s ongoing effort to leverage it without properly compensating those involved (see: this great thread from Suzanne Scott). When you consider these questions about strike solidarity through the lens of how the film and television industry seeks to leverage all available avenues for self-promotion and self-enrichment, we’re asking some really productive questions that all journalists, critics, content creators, and fans should ask themselves on a regular basis. If they feel like the industry is asking them to “step up” and change their actions in response to the striking workers, that’s a concern.

However, if I step away from the academic response and instead think about this as the editor of this newsletter/website and as a critic, I want to be expressly clear: while the complicated ethics of actively working for a studio in this climate are legible to me, I truly am baffled that anyone would perceive literally any form of engagement with media as “scabbing,” or perceive of it as contradicting one’s solidarity with the striking writers and actors. As much as my academic training has highlighted the importance of all of us being aware of how the industry might try to leverage our labor for its own ends, the notion that our labor is inevitably going to support the goals of the AMPTP rather than the goals of the WGA and SAG-AFTRA is a deeply cynical and frankly insulting view of the amateurs and professionals who operate within these spaces.

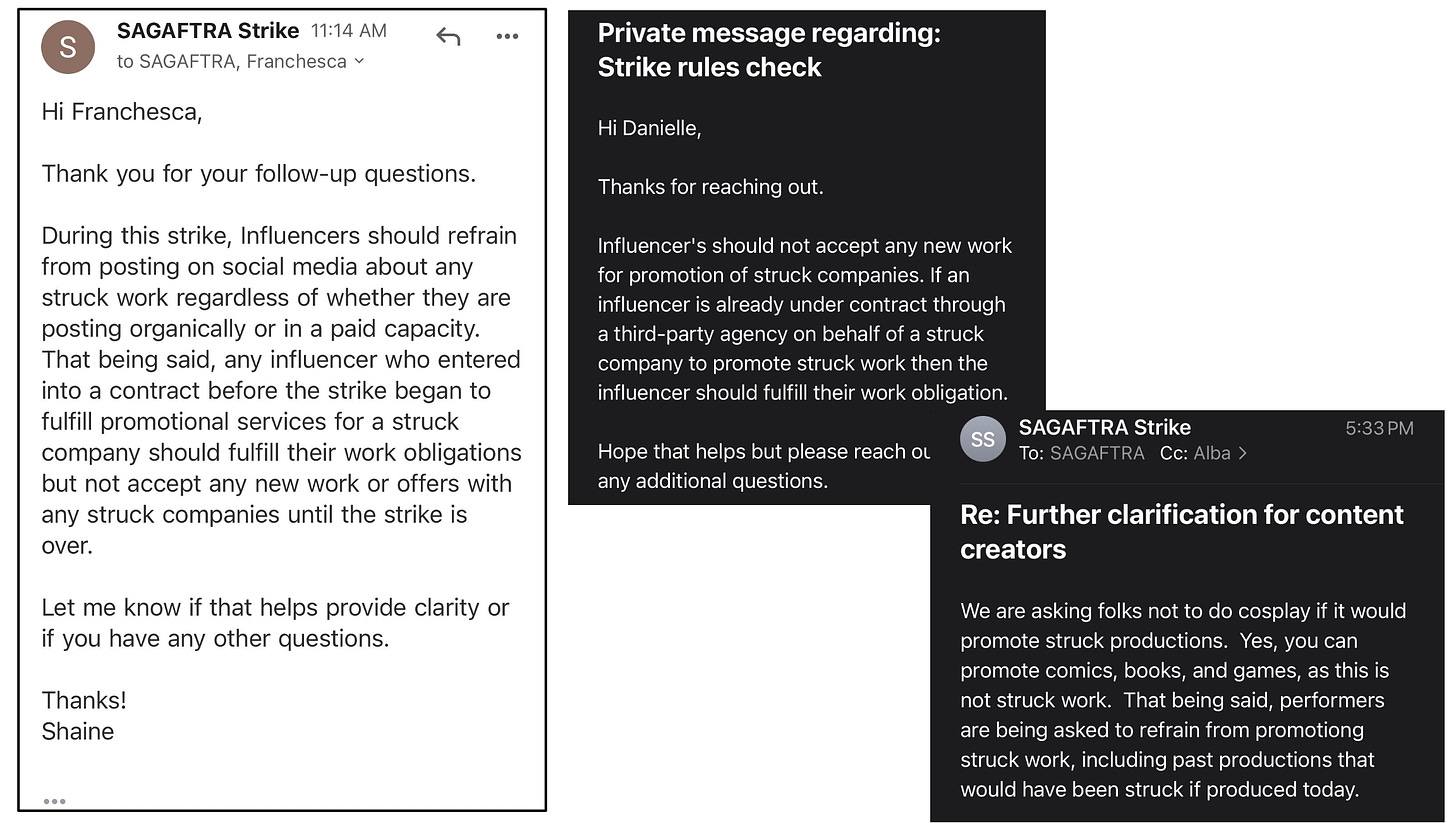

When SAG-AFTRA guidelines first began trickling out, ahead of the organization putting out specific guidance to influencers and other groups, the framing was primarily around professional consequences: if you ever hope to be a member of SAG-AFTRA, any activity you engage in that could be considered in violation of the strike order could bar you from membership in the guild. This is a particular concern for many content creators, both because there is an Influencer category within SAG-AFTRA, and because they often have aspirations to become actors or writers, a context wherein perceived support for the AMPTP and its content might complicate their future career plans.

However, while this professional imperative seemed like it would only apply to a small subsection of those who engage with film and TV online, the subsequent debate and conversation shifted toward a moral imperative that extends well beyond those who have direct ties or wish to have direct ties to SAG-AFTRA. And after starting in an influencer space where the conversation at least makes sense given how brand sponsorship is the backbone of many of those accounts, it somehow spun out into formal journalism, including criticism, as though it was possible that a critic would be accused of scabbing if they reviewed a movie that was coming out in theaters. And then the mixed messages regarding cosplay ignited concerns among fans who, ahead of San Diego Comic-Con, wondered if their choice to cosplay characters from struck series or films could run afoul of this emerging moral code of media consumption and engagement.

Again, these are all fascinating discussions on an academic level, but there’s realistically no basis for any of this activity being inherently understood as “scabbing” or “crossing the picket line,” despite the framing that’s emerged. Now, to be clear, this is absolutely a moment for increased vigilance in understanding how the industry might seek to leverage other forms of labor in order to compensate for the lack of participation from actors in promotional efforts. For fans attending Comic-Con, they absolutely should be cognizant of who they talk to and how their image is used, in ways that they might not have in a context where the studios were operating in good faith negotiations.

But when SAG messaging started defaulting to blanket policies that suggested anyone cosplaying a production of a struck company would be in violation of the principle of the strike, even if they faced no professional repercussions, the resulting conversation embodied the contradiction of this discourse. To view cosplay as strike-breaking is placing an immense value on fan labor, which in some ways validates how scholars have often thought of fans and their activity; however, it’s also flattening the nuance of that labor, and implying that those involved are either unaware or unwilling to understand their labor as a conscientious form of engagement that can and often does embody a degree of critique of industry principles. Rather than using this as an opportunity to encourage an ethical version of fandom, the discourse shifted to framing fandom itself as unethical, an unproductively two-dimensional response to a three-dimensional situation, and one that spilled over into discussions of journalism and other areas.

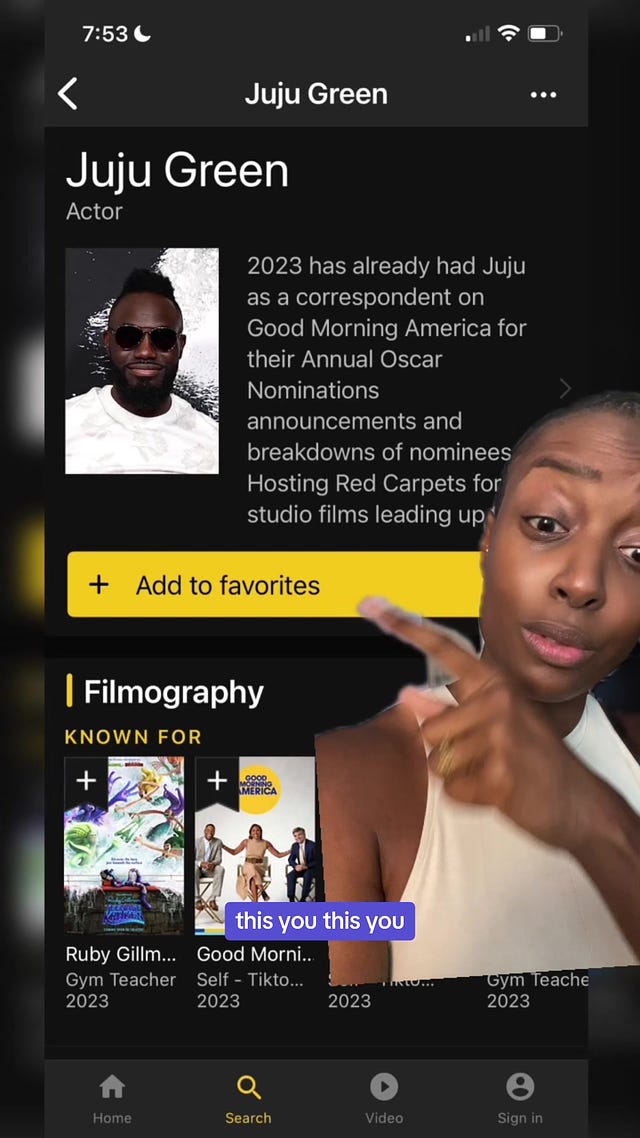

As my TikTok For You Page has been taken over by content creators navigating these vagaries, it’s become clear that there is a prevailing sense of anxiety for regular people who exist online that their actions will be perceived as in violation of these moral imperatives, and they’ll be “canceled”—read: held accountable—as a result. This is in part because they’ve seen it happen: Popular movie Tiktoker Ju Ju Green, a.k.a. “Straw Hat Goofy,” has garnered 3.4m followers for his analysis of films, and posted a “skit” basically defending his ability to keep working as he was before, placing his entrepreneurial drive above the concerns of the strike. However, he was swiftly “stitched” into oblivion by other creators pointing out SAG-AFTRA’s policy that strongly discourages promotional work on behalf of the studios, and calling out the tone deaf approach to the issue. Green has since damage controlled his way to what has become the morally acceptable position: deleting the initial skit, adopting an avatar of solidarity with the union, posting an apology video after a “listening” livestream, and creating videos talking about international films and other content not tied to struck studios, which he asks people to repost using solidarity hashtags.

And for influencers like Green or “GuyWithAMovieCamera” Reece Feldman, who posted a similar statement of solidarity that featured his commitment to taking no new brand deals (but without the flip-flopping), this balancing act is probably necessary. If you’re wondering why these moral imperatives didn’t emerge when the WGA went on strike, it’s because that strike has predominantly focused on television, where there really isn’t a significant influencer marketing apparatus. The merging of influencers into the promotional apparatus of the film industry, however, has been a dominant story of the TikTok era, and it has become nearly impossible to draw a distinction between paid and unpaid content in these circles. For these reasons, it’s productive that we’re holding big-name creators accountable for this blurred line in the midst of this labor moment, especially when they—like Green—so clearly miss the point of the moment.

However, what’s happened is this culture of accountability has been extended out to literally the entire internet, regardless of context. In the comments on TikToks about influencers and the strike, regular people are anxious that attending a convention in cosplay could somehow get them in trouble, or wondering if their cosplay prop store featuring Witcher-related items could be considered scabbing. It’s one thing for us to take this moment to reinforce how much fandom is used by the industry as a form of promotion, but it’s another for us to effectively criminalize it in a court of public opinion, especially given how much fandom can function as a check and balance on industry practice. And while I respect anyone who takes a militant approach of non-participation in relation to all screen media in solidarity with the strike, to imply this is the only morally acceptable response ignores the ways fan labor can and will function in solidarity with striking workers.

It’s this response that had even journalists and critics anxious that their own reviews of films or TV shows—as opposed to those by influencers who consistently do literal promotion on behalf of studios—could be treated as crossing a picket line; heck, as I was writing this, The Ringer’s Joanna Robinson was criticized by a Twitter user for discussing something she appreciated within Barbie. And in this area I propose a simple rule of thumb: if you are someone who was previously doing a job or engaging in activities related to—but not within—the film and television industry, you are not a scab if you continue to engage in that activity in a strike-conscious way. This doesn’t mean stopping entirely, nor does it mean continuing on as if the strike isn’t happening. It instead means operating with the understanding that this is actually a vital time for us to be discussing the media we consume and our relationship to it, and losing out on fan creativity, critical analysis, and other paratexts would ultimately weaken rather than strengthen the cause of writers and actors who are emphasizing how critical they are to the industry’s success.

Until the point that SAG-AFTRA or the WGA calls for a consumer boycott, which they are still not doing, the kind of “promotion” created by a tweet a critic writes or a costume a fan makes is not scabbing. The very premise of these strikes is that people don’t support studios or streaming services with their labor: they support the work of writers and performers, who create and bring these stories to life. And for this reason, I would argue that even SAG-AFTRA’s now clearer position on influencers is mistaken in suggesting that “organic” discussion of films or television series by content creators necessarily constitutes scabbing. There is absolutely a pathway for conscientious content creation during this strike, and while the conditions within spaces like TikTok make this harder to achieve, it doesn’t make it impossible, and I wish we were able to create more space for creators to navigate that possibility without fear of being labeled a scab.

But as Ju Ju Green’s initial inclination toward maintaining brand deals reminds us, there will absolutely be instances of “scabbing” happening within these contexts: creators hungry for access—or simply hungry—will choose to partner with studios when other big-name creators won’t, and it’s likely that some bridges will be burned in the process. And there will no doubt be fans at Comic-Con and other conventions who may not be aware of these discourses, and who will allow their work to be leveraged for promotion in ways that others might consider unethical. But we need to think long and hard about how we use this as an opportunity to educate rather than vilify, and the way this initial discourse has played out has put us on a troubling path—I’m hopeful that SAG-AFTRA’s messaging will continue to evolve toward greater clarity, but in the meantime we have the power to simply hold our judgment until we see how these online ecosystems can and will evolve to meet this unprecedented moment.

Episodic Observations

In lieu of consumer boycotts, both the WGA and SAG-AFTRA recommend donating to the Entertainment Community Fund, designed to offer emergency assistance to impacted workers. You can also always check out the WGA and SAG-AFTRA’s respective strike pages for up-to-date information directly from the unions.

In terms of critics, the Freelance Solidarity Project developed a “Critics’ Solidarity Pledge” in response to the strike—this came across my feed a number of weeks ago, and I did that thing where I agreed with it so wholly in principle that I didn’t take the time to sign it. But I’ve done so now, and I hope it has been clear across our coverage since the WGA strike began that Episodic Medium is a supportive space of both of these strikes and labor action broadly.

In the meantime, our episodic coverage of current shows continues to grow this week with the return of Justified, with LaToya Ferguson offering weekly coverage of City Primeval starting tonight. Our full summer schedule is here, and while things are definitely uncertain for fall and beyond, I stand firm in my belief that discussing and engaging with TV past and present offers valuable outlets for highlighting the creative contributions of striking workers. So stay tuned for more as we see what the future holds for this industry and our coverage of it.

It ridiculous to suggest engaging with film/program on critical level is crossing line. Central to strike is idea that work that writers and actors do is valuable and need to be treated as such. And me have never seen review whose thrust was, "me not paid much attention to acting or script in this movie, but man, those studio executives!!!"

Beyond that, while criticism not cold, objective journalism, it is journalism, and worst possible thing journalist can be asked to do is pretend something not exist like Mr. Snuffalupagus. It like saying covering Putin's invasion of Ukraine is supporting Putin. Or worse, that appreciating bravery of Ukranian people in face of invasion is somehow supporting Putin.

Me think it very, very easy to talk about how good Severance is and how much we anticipate next season while making it perfectly clear we want those writers and actors to be paid and treated well because they created something remarkable. That not pro-studio in any way. Until day comes when Episodic Medium post article praising AI as screenwriting tool and CGI ghouls as actors, me not sure how anyone could see anything on this site as crossing picket line.

I dunno--I've been following this conversation with a little bit of confusion. It never occurred to me that the guidance was applied to those outside of the SAG-AFTRA influencer agreement. And that if you wanted to get in under that agreement at some point you had to play ball. Otherwise, do what you want. But, as someone who works in politics, I can't say I'm shocked the online discourse has blown this up. The lack of media literacy on the internet / real life is pretty wild and I'm not surprised that folks online haven't drawn the line between a PR campaign and journalism.

I am curious how much of this permeates beyond one small corner of the internet. My parents (who I routinely use as a gut check on what's breaking through in political news) were up for the weekend and knew the strike was happening and even the AI and residual piece of it. However, the influencer side of things wasn't even on their radar as a thing people were worried about.