(Not) Week-to-Week: How I Learned to Tolerate the Binge Release of The Bear

Season two might still have been better released weekly, but there's *some* method to the madness in its storytelling

On the one hand, I stand by my sight-unseen belief that FX and Hulu should have released The Bear weekly in its second season. This was a show that generated strong word-of-mouth in its first season, has significant awards momentum, and features character-based storytelling that would generate meaningful engagement on a week-by-week schedule. While not every episode may be as substantive as “Fishes” or as transformative as “Forks,” there is enough thematic and narrative evolution across the ten episodes that it would have easily become one of the most talked-about shows of the summer.

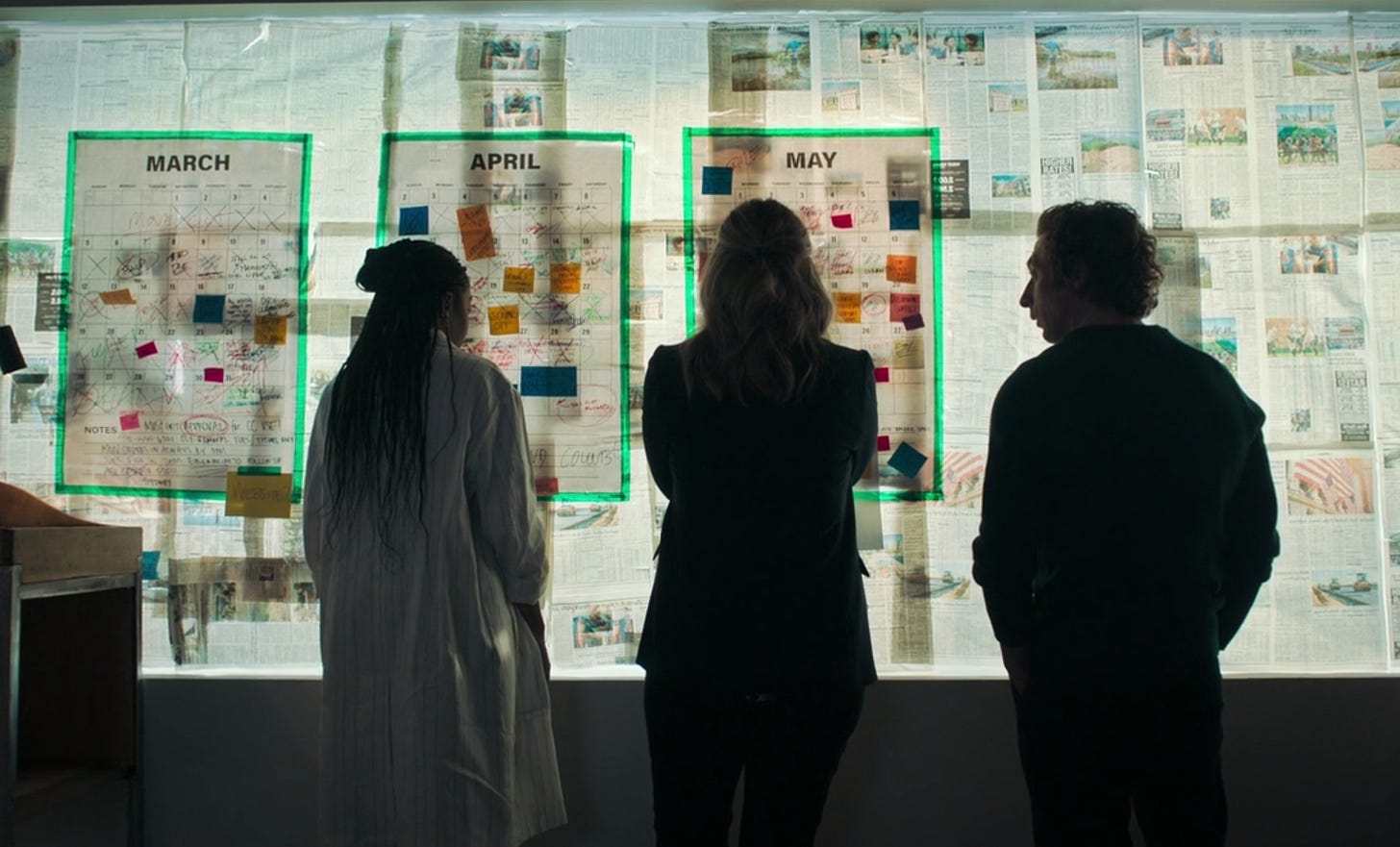

But on the other hand, as I worked my way through the second season over the past two weeks, there was one dynamic within the show’s storytelling that gave me pause, and at least made a case for the idea that a binge release was the right choice. When the first season ended, the conflict it established for the second season was a big one: faced with a financial windfall from the tomato cans, Carmy lays out a plan to destroy The Beef, pitching Sydney on a fine dining restaurant that lets them achieve all that they’ve ever dreamed of. The question at the heart of this conflict was whether or not Carmy and Sydney could pull it off, overcoming the seemingly insurmountable hurdles of financing, constructing, and eventually running said restaurant.

And what became apparent for me early on in the season is that there was no real question here. Yes, The Bear routinely demonstrates how stressful it is to open a restaurant, and shows us numerous roadblocks and pitfalls and failed tests to emphasize that this is a high-stress situation. But even after the reckless deal Carmy makes with his Uncle, and despite the team’s ambitious timeline, and as the restaurant looks more and more destroyed every time we see it, there’s never a point where it seems like this ragtag group is going to fail. When the plot does eventually bring us to the fateful fire suppression test that will determine if they’ll meet their timeline, it registers as a false premise: there’s no way they’re going to fail, because despite the onscreen chyrons laying out the timeline I can’t think of an episode where I legitimately believed The Bear wouldn’t make its planned opening day.

That’s not a criticism, to be clear. There are still plenty of stakes in the second season of The Bear even when it never feels like “the restaurant failing to open” is among them. But they are primarily personal stakes, as everyone has to collectively decide what they’re willing to sacrifice to get on this fast-moving train before it reaches its destination. The result is a season where, on an episode-by-episode basis, the core story of the season never really changes: they’re opening a restaurant, a process that is long and arduous and which the writers really don’t show a lot of interest in as an engine for the story being told. There’s a few mentions of budget, but it never becomes a crisis, and Uncle Jimmy’s apparently ever-flowing money even enables a trip to Denmark and culinary school tuition. The choice buys the show the luxury to abandon what was set up as a scrappy underdog story and instead ask a different set of questions about the kind of self-belief it takes for scrappy underdogs to embrace their potential.

And while this story would have worked on a weekly basis, I do think that The Bear’s second season is almost a series of short stories on this theme, with the restaurant’s construction as a sort of frame narrative. There’s serialization in that narrative, of course, and the show notably resists giving Carmy his own spotlight episode, with his relationship with Claire and partnership with Sydney the stories that offer the cleanest ongoing story threads. And Abby Elliott’s Natalie gets to move into the spotlight as the initially reluctant project manager, her investment in the project (and thus presence in the story) growing alongside her baby. These are fun elements in the season, don’t get me wrong, but they’re not the driving point of interest except for how they intersect either thematically or narratively with the episodes that isolate individual characters and have them exploring their capacity to live up to what Carmy and Sydney are planning.

To reiterate, I hate that we weren’t able to react to these moments in real time. I’d have loved to collectively work over the experience of Marcus’ trip to Copenhagen, which ends in an especially short story-like rescue of a man trapped under a fence. It’s a trip filled with metaphors—like feeding an invisible cat, which Carmy mentions in “Fishes” as part of his own experience—but also with a simple story about the power of encouraging someone to find their potential, and the power of believing in that person. However, it’s also about the sacrifice Marcus is making to be there by leaving his ailing mother behind, planting the seeds for the devastating moment in the finale when you realize that he’s going to need to imagine the new life he’s leading without her in it. And I do feel like maybe moments like this land better when we’re encouraged through a binge release to see the season as a connected series of stories, rather than weekly installments of a single one.

This is most strongly felt with Richie, who is the character most transformed by the adjustments to the show’s story structure. In the first season, Richie was the ultimate agent of chaos, and was effectively the cause of much of the conflict that made the restaurant’s eventual collapse seem so inevitable. But it’s stunning how much “Forks” is able to transform not just our understanding of the character, but the person himself. It’s not that we suddenly learn a tragic backstory that makes us more sympathetic to Richie than we would have been before. Rather, we see Richie’s stint in fine dining fundamentally change his approach to life, triggering a new version of himself that goes deeper than the suits he starts wearing. The feeling he has when he gets to deliver that deconstructed deep dish pizza to the table? Or when he sees the older couple get their meal comped? His desire to recreate those feelings is more powerful—at least for now—than the inferiority he’s felt for so long, and the moment when he steps up to expedite in the finale is the season’s most cathartic as a result.

But it’s not really a “season-long” arc, and I do think it probably hits a bit harder when it happened a few days after I watched “Forks” instead of a few weeks. When I eventually got to “The Bear,” it became clear that there really weren’t many arcs that were sustained across the season. Obviously, the Christmas flashback of “Fishes” becomes a key building block for multiple characters’ stories, but it doesn’t really become deeply relevant until the finale, when Donna’s run-in with Pete and Carmy and Richie’s blowout through the fridge door remind us how the Friends and Family night’s chaos evokes the intensity of both “Fishes” and last season’s “Review.” The finale was about seeing numerous threads the season introduced in fits and starts come together in what should be a moment of triumph, but which ultimately doesn’t resonate that way for our central characters because their stakes remain harder to parse than the characters like Richie, Marcus, or Tina who Carmy and Sydney sent on personal journeys with the message that they believed in them and their potential.

The problem is that Carmy and Sydney struggle to say the same to themselves. The finale’s choice to literally lock Carmy in a fridge is a good metaphor for a season where he’s really never able to take a step back and look at his life through a clear set of eyes. His is the one story that extends across the season, and it’s a journey into the idea of work-life balance, and how hard it is to establish one when your work life has given you PTSD, your family life has given you PTSD, and the choice to use work to escape your family left you devoid of any semblance of a life. As someone who suffered through reviewing the final seasons of Shameless, it’s incredibly rewarding to see Jeremy Allen White being given a compelling story to explore, even if it feels inevitable for the sake of the show’s future ability to generate conflict that Carmy remains trapped in a self-destructive pattern. He literally can’t see that the restaurant runs smoothly in his absence, or that the man he thought was his former abuser was just someone who looked like him, but he torpedoes his relationship with Claire anyway, steadfast in his belief that his career is incompatible with personal connection. Because the truth is that reality doesn’t matter: it’s all whatever’s in his head, which is a huge part of why Richie evokes Donna, igniting their fight and sparking a conflict that the season leaves very much unresolved.

Carmy remaining locked in the fridge means we also don’t get full closure for Carmy and Sydney, with the latter experiencing her own PTSD as the sound of the ticket printer echoes even as the last diners have left the restaurant. If this truly is “the thing” as her father suggests, that means this is now her life, and that is a terrifying, vomit-inducing reality for someone who has experienced failure before. Carmy and Sydney spent the season building up the people around them to support their vision, but even though Sydney might have figured out how to edit down her menu ideas, she doesn’t have the peace of mind she’d need to not be terrified by what’s still ahead of them. The finale doesn’t need to remind us about the financial pressures of filling tables. The loss of a chef to a crack cocaine habit isn’t a troubling setback. The conflict of the third season isn’t whether The Bear can be successful—it’s whether the chefs who made it a success will be able to get their heads around the task ahead of them in a way that also allows them to function as human beings.

It’s an evolutionary jump for the show as a whole, delivering a second season of greater ambition that deepened my connection to the show and its characters. And while I’ll reiterate once more that I do feel this would have been just as effective if we’d had it spread out over nine weeks and gathered once a week here at Episodic Medium to discuss each episode, I do think there’s something about being able to dive into this evolution at our chosen pace. The transformation of The Beef into The Bear may not have a great deal of suspense attached to it, but there’s a significant amount of growth in terms of the show and its characters, and the sum total of that probably resonates more when it happens over a shorter period. But I also hope that, should the show continue to evolve in ways that might no longer make this true, they’ll continue to revisit the question of a release strategy in the future, lest one of television’s strongest shows find itself trapped to a model that doesn’t serve the stories it wants to tell.

Episodic Observations

The internet has already written all the stories about the season’s cameos, but I think it’s such a great example of using the audience’s inability to erase big name stars’ past roles and using them exclusively to play larger-than-life figures who loom over the characters. It means that the cameos’ prominence in our experience matches how they resonate for the characters, whether it’s Will Poulter for Marcus, Olivia Colman for Richie, and of course Jamie Lee Curtis for the entire family.

I will say it’s notable to me that they specifically emphasize that Mulaney and Paulson couldn’t make it for the Friends and Family opening, implying that they are more of a presence in these characters’ lives. Meanwhile, I still don’t entirely know how Bob Odenkirk’s character was related to anyone, which really struck me during “Fishes”—part of the disorientation of the episode is the complete lack of exposition at who we’re meeting and their relationship to everyone involve, adding to the claustrophobia.

My favorite small moment in the season was the quiet beat where Tina calls Ebra after he stops coming to the culinary classes. It was not a shocking development: we could clearly see him falling behind where Tina was succeeding. But seeing her anxiety over being alone in that environment play out, and then her big triumphant karaoke moment, and then the resolution with the job at the takeout window? It’s not a story that gets a full episode to itself, but it really resonated for me.

I liked Molly Gordon’s Claire, even if the sheer earnestness of the love story kind of occasionally seemed at odds with the show’s allegedly comic dynamic. The scene of them in bed together was particularly cheesy in ways that felt very deliberate, but which maybe went too far into that well for me. I don’t think the show is suddenly going to become driven by this OTP, but I do expect we’ll be hearing from her again, given that they chose to play the voicemail and all.

I’m sorry, but as much as Richie might be transformed, I simply do not believe that he had the money for after-market Taylor Swift tickets, and do not believe that he would have understood how to navigate the pre-sale process.

There’s something especially cruel that I’m posting a two-week late review of the season, compared to the general pace of postmortem content, and yet I’m still doing so before those in international markets can access the season legally. A bizarre choice, that one.

There’s been no shortage of discussion about the show’s soundtrack, as you can turn to both Uproxx and Salon for detailed breakdowns of the song choices this season. I’m curious to see how the show’s first season fares in the Music Supervision category at the Emmys, which has yet to honor a half-hour series. I definitely think that the use of R.E.M.’s “Strange Currencies” will make them a strong contender next season, as conspicuous supervision seems like something that would be rewarded in this case.

Programming note: Lisa Weidenfeld’s reviews of The Afterparty begin on Wednesday, while Noel Murray’s coverage of What We Do In The Shadows returns on Thursday, so if you’re not a paid subscriber, now’s a great time to get started as the summer kicks into full gear.

Putting my comments on The Bear in separate post than the stuff on the release model:

I loved season 2. It is honestly one of the best things I have ever seen on TV. The standout episodes for me were "Honeydew" and "Forks", but they were all great.

But as I've read the conversations at times I have felt like I have been watching a different show than everyone else. Many of the comments I have read say something to the effect that people find the show very stressful to watch (in a good way) because of the intense kitchen scenes and big blowouts a la "Fishes". Yes, those scene are there and make an impression, but I think if you count minutes they don't actually make up much of the running time and to me they are not at all what make The Bear special. For me it's the long conversations: Marcus and Chef Luca*, Richie and Chef Terry, Syd and her dad, any number of quieter conversations from "Fishes". It's people talking quietly and passionately about real things - like Aaron Sorkin but far less mannered. You rarely see that on TV and I thought it was outstanding.

* Another favorite moment from "Honeydew": Marcus's first attempts to make the scoops for the gelato-whatever-it-was dessert and Chef Luca's feedback. "No", "Worse", "Try again", etc. There is layer of tension there - Will Marcus be able to do this? - but there is no bite to the constructive criticism and no offense taken. Two people being professionals. I loved it.

I really think this was one of the best seasons of any show in recent memory. It might - MIGHT - even be better than Succession S4, which is just not something I thought was possible a few weeks ago. Acknowledging that any upcoming Emmy nominations are for S1 (which I still think was the best show of last year), if Ted Freaking Lasso beats The Bear for anything, I'm gonna be throwing a ton of forks.