Episodic Classics: Enlightened, "Not Good Enough Mothers" & "Sandy"| Season 1, Episodes 5 & 6

Two stellar guest directors refuse to let Amy off the hook

Who was Amy Jellicoe? This is before Open Air, the cripplingly expensive Hawaiian rehab where she reassembled her shattered pieces post-Abaddonn breakdown into the injustice-seeking ICBM Enlightened presents us with. Before Abaddonn, even—what made Amy Jellicoe tick? From glimpses in the first four episodes, we can surmise that Amy was as committed to her job as corporate buyer as she’s become avid recycler and champion of all she deems worthy of one. In flashbacks, we’re left to surmise that the corporate rat race, with its constant ambition and side-eyeing jealousy, contributed to her succumbing to substance abuse (and a very unwise office affair with her smarmy boss, Damon), and likely exacerbated her widening split from equally troubled husband Levi.

This week’s episodes don’t so much explain Amy as they drop unexpected little facts about the pre-Enlightened Amy that blessedly pull our attention from two of the most uncomfortable outings so far. I’ve had a pair of critic friends (and they know who they are) congratulate me on this gig while asserting that, while they wish me well, they have not, nor will they ever watch Enlightened. Never. And I get it. Hell, I pitched this Classics rewatch to our serene benefactor, Myles, and I have to steel myself each time I fire up my DVDs (because of course, I bought both seasons of Enlightened on DVD at the time)‚ because I know what’s coming. In the long run, as those critic friends would see if they followed me on this adventure, that means I know about the (SPOILER, I guess), complicated but, yes, transcendent place where this series concludes. But I also know about episodes like “Not Good Enough Mothers” and “Sandy," a collective hour of television almost unbearably squirmy enough to turn the unwary and understandably cringe-averse off forever.

“Not Good Enough Mothers”

“Uh, go away.”

Amy Jellicoe’s emotions are stripped wires, exposed nerves prepared to vibrate to crackling life at the merest brush of injustice. “Not Good Enough Mothers” begins with Amy watching the morning news, where a story about an immigrant mother of two facing deportation registers on Amy’s face as a classic tragedy. Of course, such a situation is, in its all-too-common way, just that—the mother, who’d come to the U.S. from Mexico illegally, has two young American citizen daughters, who are shown in tearful confusion clinging to their mother as she pleads in Spanish for someone, anyone, to help.

Enter Amy Jellicoe. Yelling “Fuck you, asshole!” in her mother’s tidy kitchen at the smug prosecutor lecturing the terrified woman about consequences for her illegal entry, Laura Dern makes Amy’s entire being flood her features as a mask of righteous, horrified, incredulous anger. Her mom, a passively reactionary older woman who’s created her own safe little world of rose gardens and small dogs, sighs about the woman’s plight, yet offers up that a mother shouldn’t put her children in such peril. “That mother’s just a child, too,” a weeping Amy repeats as mother and daughter watch footage of the immigrant mother—all protests and legal options having failed—being driven away, her young daughters pressing their tiny hands to the police car’s window.

Enlightened isn’t a show about the American immigration debate, of course. It’s about Amy Jellicoe, a privileged white woman whose personal transformation makes her both acutely sensitive to situations she feels in her bones are just wrong, and uniquely unequipped to de-center herself in her resulting, scattershot efforts. Amy takes it upon herself (enlisting Mike White’s ever-obliging, if bemused Tyler for practical help) to do something about this family’s plight—even if it means she asks boss Dougie for a long lunch to attend a protest rally after she’s arrived to work 40 minutes late because of her uncooperative car.

Enlightened, at it’s most confrontationally offputting, plays out as a series of outraged reactions by everyone in Amy’s life to her me-first demands. (After all, can’t they see all the good she’s trying to do?) Here, Timm Sharp once more shows Dougie’s infantile, if understandable, response to his new employee’s habit of treating Cogentiva as mere pit stop on her way to the next, better thing, exploding, “I’m a nice guy, but, push me, I’m a serial killer!,” punctuating his tirade with another heedless hurling of objects. (His water bottle whacks the backside of an unsuspecting guy at the photocopier.) Dougie should in no way be in charge of anything, but he’s also not wrong that Amy has genuinely no perspective on her beliefs in relation to other people’s lives. Her unimpressed basement coworkers aren’t responsive to Amy’s typically laser-focused pitch to join her, and her lonely trek to the vigil (with Tyler in tow) winds up a washout thanks to the soaking rain that thrums down throughout the entire episode.

Then Amy latches onto a bit of over-lunch gossip from Tyler that HR rep Judy (Amy Hill) might be a lesbian like a drowning swimmer with a buoy. “Women are more community-oriented,” beams Amy to the quizzical Tyler, “Women who love women are gonna be even more like that! She’s a fucking lesbian? This is awesome!” This, along with her plan to woo Judy into supporting a new Abaddonn women’s activist group, is Amy Jellicoe at her more manically unrelatable. At the ensuing dinner, the reluctantly attending Judy (enticed with the promise that Amy’s buying, she orders the lobster), even more reluctantly conforms her sexuality under awkwardly supportive roundabout questioning, before sighing and half-promising to consider the idea—but only if Amy can drum up support. “Besides you, Amy,” she admonishes, repeating herself for emphasis.

Throughout the episode, Amy’s car troubles provide yet another illuminating interaction between Amy and mom Helen. Despite allowing her adult, homeless daughter to crash in her unused guest room indefinitely, Helen steadfastly refuses Amy the use of her safely garaged automobile, responding to her daughter’s increasingly incredulous demands for the loan with the stubborn fact that Amy is not on Helen’s insurance. (In response to Amy’s exasperated claim that she’s not going to just run somebody over, Helen brings up how the 16-year-old Amy did just that. She might also have brought up the more recent time when Amy stalked her married former lover and accidentally rear-ended his parked car.) “I will never stop asking you!,” is Amy’s furious warning after once more begging for the keys for her outing with Judy, Amy’s hissing anger another flash of how their mother-daughter dynamic’s outwardly placid waters are harboring plenty of storms.

Another time Amy has to ride the bus comes when Michaela Watkins’ Janice airily drops the time and place of Krista’s upcoming baby shower, which is face-draining news to Amy. Confronting her former assistant nets Amy a belated invite, but once she arrives (sans present) it’s abundantly clear (to us, at least) that this is yet another executive-level event that the basement-demoted Amy has pointedly been excluded from. Here again, this is Amy at her most queasily clueless, as she—blinkers firmly in place—hijacks the best friend speech (from a guesting Riki Lindhome) in order to launch into a pitch for the attendees to join her in rallying in support of her newest pet causes. It’s teeth-grindingly awful to watch as everyone averts their eyes (especially once Amy, laying a guilt trip on how good they have it in comparison, brings up prenatal deformities to the very pregnant Krista), and emblematic of just how willing Dern and White are to push their protagonist far out of viewers’ comfort zone.

When Krista upbraids Amy at the shower’s conclusion (Watkins’ Janice watching on in majestic disdain), she asks, “I don’t think you even understand why I’m angry at you.” Amy truly doesn’t. It’s tempting to pin her obliviousness to her newfound zealotry for do-goodery, but thinking back at her behavior toward then-assistant Krista in the first episode (and Amy’s later outraged accusation, “Krista, I thought we were friends”), Amy’s blinders have always been securely in place. Returning dejected to her mother’s house, she peevishly takes out her disappointment on Helen, bringing up the car once more before slouching off to her (guest) room.

Does Amy have valid points? That’s the question. From Helen’s hints, her decision to defer to her insurance policy over Amy’s convenience isn’t wildly inappropriate, and Helen’s resoluteness in defending the life she’s made against a daughter with a penchant for disastrous impulsivity is at least understandable. It was a jerk move for Krista not to invite Amy, but this Amy is not only frequently insufferably self-centered, she’s also—as Krista points out to her—no longer someone she’s professionally obligated to deal with.

Amy is bursting with enormous energy and outsized dreams for making the world itself a better, wiser, more just place, but too often incapable of admitting inconvenient facts (like the needs and feelings of anyone but herself) into her hair-trigger action plans. In the end, Amy, who’d previously allowed her time riding public transportation to see everyone around her as as miserable as she was (or, in an unwise bit of self-help book strategy, see them as Helen), has another of her nighttime epiphanies. Lying in bed, we hear her decide to forgive—and to change.

Putting an afghan on her mother as Helen dozes on the couch, Amy says she’s lived in a “world of not good enough mothers,” finally extending her empathy for the now-deported mom’s complicated decision-making to her own mother, and herself. With a vision of the two now-motherless little girls standing uncertainly in the bedroom doorway, Amy states, not unkindly, “I will be patient with you. I will be tender. I will be the mother I wanted you to be.” The next day, uncomplainingly riding the bus once more, she projects such unselfconscious goodwill that she coaxes a smile from two impassive fellow riders, Dern even sparing a smile right for us down the lens of guesting director Nicolle Holofcener’s camera. With Paul Simon’s “Mother and Child Reunion” playing us out of the episode, we see Amy take a cab to a small house, where we watch her hand over a bag filled with toys she’d bought for the little girls on the news.

And then she leaves. (No shades of Liz Lemon snooping around to make sure her Christmastime donations to supposedly underprivileged kids are satisfactorily dispersed.) And the sun finally comes out. Enlightened’s half-hour episodes begin and end with Amy Jellicoe’s hopeful voiceovers, which in Laura Dern’s impassioned voice carry enormous conviction and weight, regardless of where we think we know things are headed. The first one always sets her up for disappointment. The second one revels, with rueful hope, in what she claims to have learned. In what she will do better. It could be a joke. And maybe it is. After all, it can’t be that easy, can it?

“Sandy”

“I’m really glad you told me how you feel even if it hurt me.”

When things go wrong, and the visiting friend she’d met at Open Air turns out not to be the beatific exemplar she thought, Amy Jellicoe collapses on the bed in her mother’s guest room. Laura Dern has the skill of imbuing Amy with such glowing, hopeful energy that, when she inevitably deflates, it feels heartbreaking even if we’ve watched Amy make an ass of herself.

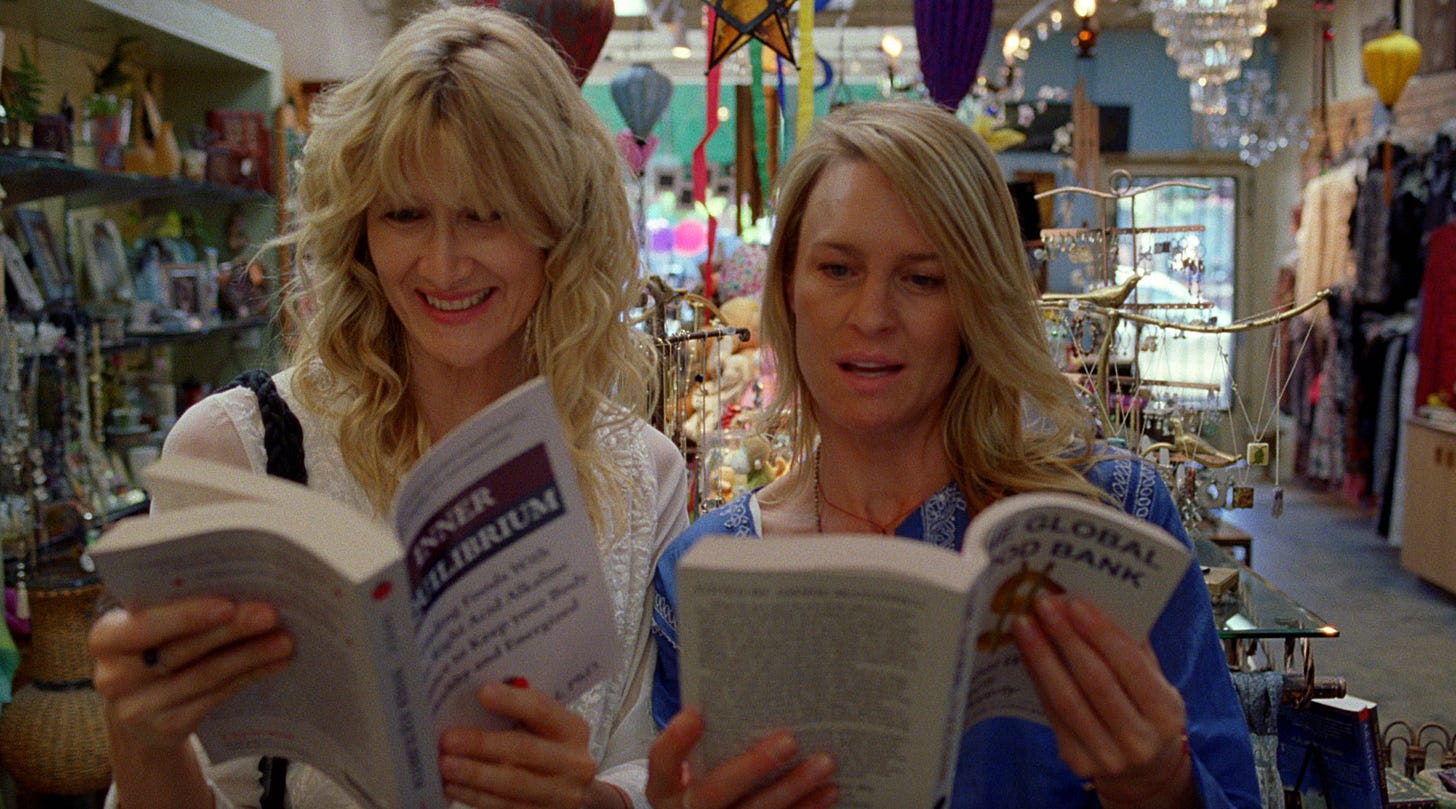

And, in “Sandy,” directed by Jonathan Demme, she does. Sandy is played by Robin Wright, and it’s easy to see why Amy sees her former rehab-mate as a figure to be emulated. Both Dern and Wright’s characters are blonde, impossibly rangy, and dress with flowing casualness like a 1970s folk star. They both wound up at Open Air thanks to a work-related meltdown. (Sandy explains to Helen that she’d been a high-powered political speechwriter “and flak.”) They have their shared intimacy in Hawaii to draw from (“I’ve heard so much about you!,” Sandy greets Helen, the unspoken fact that she and Amy were in group therapy together freezing Helen in place), and immediately use their bookstore excursion to buy each other their favorite self-help books. Their initial greeting at the airport, with Amy hopping up and down in anticipation until they can embrace in mutual glee, is bathed in sunlight nearly as welcoming as Amy’s wide smile.

“Every once in a while, fate takes pity on you, and sends you a friend,” Amy narrates over Mark Mothersbaugh’s plinking xylophone theme, and we can hear the relief in her voice. Amy has a friend who understands where she’s been, and who—she imagines— understands what she wants herself and the world to be. Sure, she hasn’t heard from Sandy in a long time, but with the yoga instructor in town to teach at some seminars, Amy is blindingly certain that things are about to get better. She has a friend.

Naturally, Sandy stays at Helen’s with her, Amy’s excited invitation heedless of the fact that her aging mom is already contending with one exhaustingly positive and opinionated guest. Indeed, there’s something of a Three’s Company gag when Helen, worriedly stalking outside the guest room, momentarily interprets the friends’ pain-pleasure yoga moans for lesbianism, and when Amy leaves for work the next morning (leaving Helen alone with Sandy) Sandy exhausts her host with an entire day’s worth of advice about everything from her private sex life to the processed foods in her cupboards. (“Amy? I’ll be calling you!,” is the aghast Helen’s ominous promise to the departing Amy, while the towel-clad Sandy lounges on the living room sofa.)

Are there warning signs that Amy is setting the seemingly more together and serene Sandy up on a pedestal prematurely? Yeah. Overhearing snatches of Sandy’s cellphone conversation through a convenient vent in the wall, Amy is puzzled by Sandy’s description of her as someone “out of context.” And while Amy buzzes into Abaddonn flushed with excitement over the plan to have Sandy teach the sun-deprived office drones of Cogentiva yoga (something the leering Dougie hurriedly assents to at the promise of spandex-clad women “with their legs behind their heads”), her planned apology to Krista over the baby shower tests Amy’s renewed positivity with its strained politeness. (Amy did finally get a baby gift—an organic hemp baby sling that Krista is clearly never going to use.)

With the fed-up Helen putting her foot down, Amy sends Sandy on her second night in town to stay with Levi, of all people. (We never hear that conversation, but I can only imagine.) Red flags presented by that sleeping situation only belatedly appear to Amy, however, as she can’t help spending the night nudging them both with texts and unsuccessfully trying to steal peeks into Sandy’s ever-present journal (an Open Air practice Amy ashamedly admits she’s neglected.)

The next day at work, with Amy having for the first time ever actually lured a collection of skeptical coworkers to her cause (of a free yoga lesson in Cogentiva’s spaciously immaculate mainframe room), she has her gnawing fears confirmed. Sandy bails on the promised engagement, leaving the workout-clothed workers (including, miraculously, Krista and Janice) to shake their heads at another Amy Jellicoe plan gone predictably sideways. Receiving no answer from either Sandy or Levi’s phones leads Tyler to speculate, “Maybe they’re sleeping—together.” Tyler’s role on Enlightened will expand wonderfully, but even in his sparsely strategic early appearances, Mike White lends the painfully overlooked office drone a prankish glint. He may barely register on Amy’s horizon-scanning radar as a rule, but that only allows Tyler to slip in a sly little riposte to her self-obsessed monologuing here and there.

Slipping into Eli’s apartment with that hide-a-key, Amy—like Helen—plays Mr. Furley for a moment, mistaking what turns out to be an intense massage session in Levi’s bed (Levi is fully nude under a sheet) for the one outcome she’d been dreading. Excusing herself from Sandy’s ensuing preparation of a truly healthy/appalling-looking smoothie in Levi’s kitchen, Amy can only plead with Levi, “Please don’t fuck her.” Levi, for his part, seems more in tune with Helen, explaining that he’s spent the entire day nodding along to Sandy’s babbling stream of lifestyle advice. (“She’s like a Nazi interrogator!,” he complains, even if the scenario of a second night with a beautiful yoga instructor with a penchant for full-body contact doesn’t seem to give him that much pause.)

Back at (Helen’s) home, Amy collapses. Sandy brushing past her Cogentiva no-show as “flaking” and the inherent uncertainty of a Levi-Sandy hookup leaves Amy bereft in the way that only Amy Jellicoe can be. And then Helen comes in to the guest room with an armful of fresh-picked flowers from her garden. As she arranges them in a clean glass bowl, she notes after hearing Amy leave a genuinely apologetic message for Krista about the yoga class that wasn’t how Amy, as a child, always formed strong—and inevitably fleeting—attachments.

“When you were young,” Helen begins, concentrating on her arrangement, “you had so many best friends. You’d get a fix on a girl, and then you’d have a falling out. And all the tears. And then, a new girl would show up. And she’s your best friend. So involved.” Gesturing to the flowers, “I picked these this afternoon. I thought you’d like them.” And then she leaves. The gift of a dozen or more, perfectly coral-pink, hand-grown roses left behind in her grown daughter’s room.

The airport goodbye the next day sees Amy trying to claw back some of the seemingly unbreakable bond between them, but she can’t stop obsessing over whether Sandy and Levi slept together. Crestfallen that Sandy doesn’t agree that Levi is ready to drop everything and head to Open Air (as Amy had hoped would be the outcome), Amy responds to Sandy’s serene platitudes about their connection by stating, “There are things you’ll never know about me, just like there are things I’ll never know about you.” Sandy’s answer? A shrug, a smile, and a noncommittal, “I guess.”

As Amy wrestles one last time with the prospect of storming the airline gates to demand clarification, we hear Amy Jellicoe’s voiceover again to end the episode. “Let it go, let it go,” we hear, as Demme’s camera stays on Dern’s face, first contorting in anguished indecision, then, after a sigh, relaxing as she repeats, once more, “Let it go.” You cannot look to others for validation of who you are or whether you’re good, or wise, or enough. As we follow Sandy to the gate and watch her sit and finally open that ornate journal, we see—just pictures of flowers. Hand drawn in ballpoint and signed large with her own name on every page.

Stray observations

Michaela Watkins Janice remains a comic assassin in her brief scenes. Cornered by Amy in the coffee line, Janice’s offhand, “I saw you walking in the rain. I almost stopped and gave you a ride,” is delivered with a majestic lack of remorse.

Another example of Tyler perhaps having more of an edge than he seems: Cobbling Amy’s nebulous idea of a women’s group at the laser printer, he dubs it Women’s Association of Abaddonn, the resulting acronym’s inevitably belittling sound lost on the excited Amy.

It should make us like her more, but Sandy’s silent ability to calm Helen’s yapping little dog is strangely unnerving.

Sandy misses the implication when she explains to Amy where her mom is after having spent an entire day with her. “Oh, she’s lying down in her room,” Sandy says happily.

But I would not give you false hope (no)

On this strange and mournful day

When the mother and child reunion

Is only a motion away— Paul Simon, “Mother and Child Reunion”

Dennis, I finally got around to watching this show and it's all because of the AV Club's old reviews of it which were always so positive, and now seeing it come around again here on Episodic Medium I thought I'd finally make time. I've been enjoying it so far.

I actually had to mute the episode during Amy's speech at the baby shower because I couldn't handle the cringe 😂

Even when she's trying to do good or latch onto a cause, Amy is just the worst, yet the cringe comedy which comes from it is so glorious, yet difficult to watch.